(RNS/Unsplash/Florian Schmetz)

Possibly the most oft-repeated statistic in American religion is the rise of the religiously unaffiliated from just 5% of the population in the early 1970s to about 30% of adults in 2022. In a field where shifts typically move at a glacial pace, that demographic factoid may represent the most abrupt and most consequential shift in American society in the postwar period.

But there is a more recent such phase shift, when American religion changed incredibly quickly, in whose aftermath we feel even today.

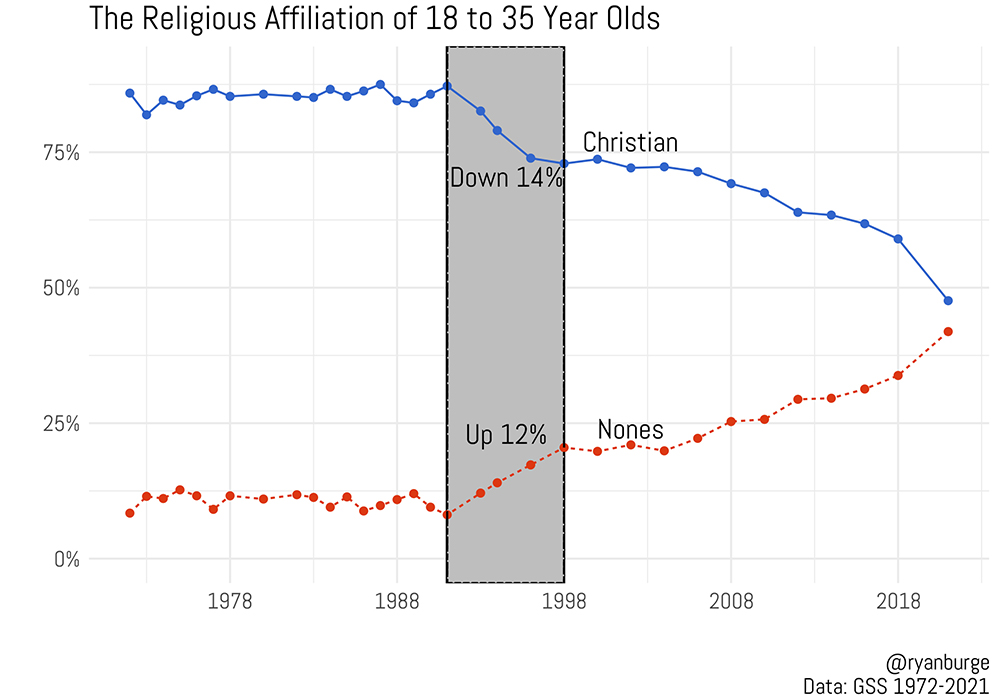

Using data from the General Social Survey, which has been fielded consistently from 1972 through 2021, and restricting the sample to adults between the ages of 18 and 35, a single decade comes into sharp focus: the 1990s. It's a moment when young Americans seemed to lose religion virtually overnight.

In 1991, 87% of young adults indicated that their faith was Christian, primarily Catholic and Protestant. Just 8% of this age group said that they had no religious affiliation.

In 1998, only seven years later, the share of 18-35-year-olds who said they were Christians dropped a full 14 percentage points to 73%, while the percentage who answered "none" jumped to 20%, an increase of 12 percentage points. A ratio that hadn't changed at all between 1972 and 1991 had moved by double digit percentages in seven years.

“The Religious Affiliation of 18 to 35 Year Olds," based on data from the General Social Survey (Graphic by Ryan Burge)

What caused this change to occur at this specific point in American history? It's hard to pinpoint just one thing, but there are possible culprits.

The end of the Soviet Union: On Christmas Day 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as president of the Soviet Union and Boris Yeltsin took power over Russia.

Described by historian Kevin Kruse and others as a conflict between the virtuous Christian capitalists of the United States and the godless communists of the Soviet Union, the Cold War was a time when "In God We Trust" first appeared on American currency and "Under God" was added to the Pledge of Allegiance.

By the mid-1990s, being nonreligious no longer meant being un-American, giving permission for a lot of closet nones to begin expressing their true feelings on surveys.

Backlash against the religious right: As I describe in my book "The Nones," evangelical Christians made up about 17% of the U.S. population in 1972; in 1993, that had rised to 30%. As Ruth Braunstein argued in The Guardian earlier this year, "backlash against a radical form of religious expression leads people to distance themselves from all religion, including more moderate religious groups that are viewed as guilty by association with radicals."

When faced with the strident rhetoric of the Revs. Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson and the rest of the religious right leaders, many moderates headed for the church exits and never came back.

Advertisement

Political polarization: In his excellent 2018 book, The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political Tribalism, Steve Kornacki makes the point that in 1994 Newt Gingrich led a Republican takeover of the House by refusing to compromise with those on the other side of the aisle. Gingrich's bomb-throwing approach appealed to conservative Christians by painting Democrats as morally inferior and godless. Many young Americans chose godlessness.

The internet: Demographers ignore the impact of the World Wide Web at their peril. It would make sense that as young people were exposed to other faiths on the new technology — and saw the faults in their own — some would leave faith behind altogether. But the data doesn't entirely support it. According to the Census Bureau, just 20% of American households had internet access in 1997. While many young Americans had access to the web in school before they had a home connection, the effect was likely only to accelerate the trends cited above.

The echo of this falloff is what we are living with today. Many of those who fled from religion in large numbers during this period also chose to raise their children without religion. Today nearly half of those children — millennials and Gen Zers — say that they have no religious affiliation.

Editor's note: This commentary is part of Ahead of the Trend, a collaborative effort between Religion News Service and the Association of Religion Data Archives made possible through the support of the John Templeton Foundation.