A sign reading "All will be well" hangs on a statue of St. Pope John XXIII in Zogno, Italy, near Bergamo, March 22, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Flavio Lo Scalzo)

Nov. 4 was the feast of St. Charles Borromeo, the great reforming cardinal-archbishop of Milan. It was also the 63rd anniversary of the coronation of St. John XXIII, who had been elected pope on Oct. 28, 1958. John chose the date because he had a great respect for Borromeo and significant knowledge of him, too. Both that respect and that knowledge would play a part in his decision to convoke the Second Vatican Council, the reception of which remains the principal task of the universal church in this synodal process we have begun.

These were on my mind last week when Twitter erupted after Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, published the text of a deeply regrettable speech he delivered this week at a conference about the church in public life. The contrast between John XXIII's most famous speech and Gomez's text is a profound one.

On Feb. 23, 1906, Fr. Angelo Roncalli had accompanied Bishop Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi of Bergamo, Italy, to Milan where the bishops of the province had a meeting. Roncalli and the other bishops' secretaries had some free time and the future pope was snooping around the library when he found a set of volumes labeled "Archivio Spirituale — Bergamo."

They contained the acta, or records, of Borromeo's pastoral visitations in the years after the Council of Trent in 1545-63. Roncalli, who taught church history at the diocesan seminary, undertook the editing of these records.

I have been rereading the decrees and canons of the Council of Trent and, of course, their method is so different from that adopted at Vatican II. Trent issued anathemas, condemning specific ideas, although not specific persons.

Advertisement

But what is most remarkable to me is not the many ideas that the council fathers at Trent ruled out of bounds, but the many ideas that they did not anathematize. They were at pains not to resolve all theological issues, only to indicate what was out of bounds. Within bounds were a variety of theological positions on vital issues, many of which would become sources of controversy in the years ahead.

For John XXIII, Trent was not — or at least not only — the polemical antidote to the Protestant Reformation. It was a reforming council that changed many, if not most, of the forms of the Catholic faith, from the requirement of a seminary education for the clergy to new canons about what constituted a valid sacrament of marriage to a deeper understanding of the doctrine of justification. The council fathers insisted on human freedom and responsibility in the face of theories of predestination that circumscribed human freedom, propagated by John Calvin before the council and later embraced by the Jansenists.

Consequently, when John XXIII opened the Second Vatican Council with his magnificent address Gaudet Mater Ecclesia, he sketched for the assembled bishops a positive vision of their convocation and mission.

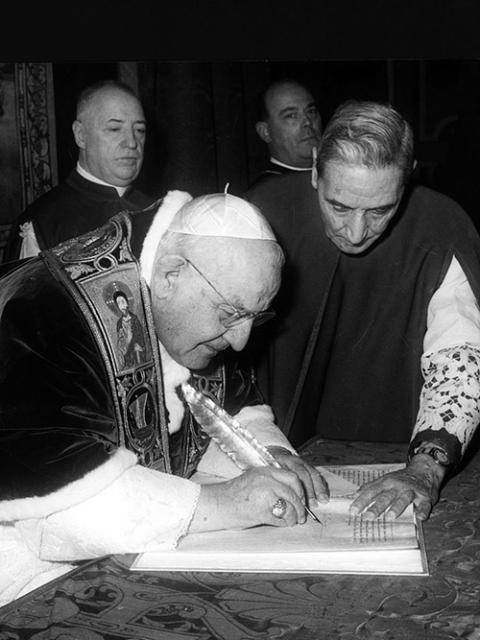

Pope John XXIII signs a papal bull opening the Second Vatican Council in 1962. (CNS)

Remember that in 1962, most of the gathered bishops — and most of the world's adults — could easily remember some of humankind's most somber events: the trench warfare of the First World War, the forced starvation of the kulaks, the Nazi subjugation of most of Europe, the Japanese brutalities against the people of China and other neighbors, the indiscriminate bombing of cities by all combatants, the revelations of the Holocaust and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. John and the council fathers were closer in time to the liberation of the Nazi death camps than we are to the attacks of 9/11.

It was against this historical backdrop that he opened his address with the words "Mother Church rejoices."

The most stunning part of John's speech that day, and certainly the most quoted, was this:

It often happens, as we have learned in the daily exercise of the apostolic ministry, that, not without offense to Our ears, the voices of people are brought to Us who, although burning with religious fervor, nevertheless do not think things through with enough discretion and prudence of judgement. These people see only ruin and calamity in the present conditions of human society. They keep repeating that our times, if compared to past centuries, have been getting worse. And they act as if they have nothing to learn from history, which is the teacher of life, and as if at the time of past Councils everything went favorably and correctly with respect to Christian doctrine, morality, and the Church's proper freedom. We believe We must quite disagree with these prophets of doom who are always forecasting disaster, as if the end of the world were at hand.

Good Pope John urged that "we should see instead the mysterious plans of divine Providence which through the passage of time and the efforts of men, and often beyond their expectation, are achieving their purpose and wisely disposing of all things, even contrary human events, for the good of the Church" (emphasis mine).

It is easy to become a prophet of doom. Some of our friends on the right see nothing but gloom when they look at the increased activity of the state in society, or the admittedly deranged excesses in culture that our free society permits, or the truly sad increase in the number of broken homes and shattered neighborhoods.

Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez addresses the Congress of Catholics and Public Life in Madrid by video Nov. 4, 2021. (NCR screenshot/CCVP)

Some of our friends on the left are made gloomy, not without reason, by the persistence of racism, the growing inequality of wealth in our society, and the inability of humankind to face the climate crisis that impends truly horrific scenarios.

Pope Francis seems to me to be a lot like Pope John in that they look at the same sociocultural and ecclesial landscape as the rest of us, and they seek to find the good and the hopeful. Thence they seek to encourage, not to condemn, certainly never to condemn a person. They are as ready with a smile as others are with a complaint or a criticism. Both popes tolerate much dissent, even from those close to them.

The contrast with the Gomez talk could scarcely be more acute. It showed him to be a prophet of doom for our day.

The archbishop warned about secularization in terms that were simplistic, made sweeping generalizations about, and was sharply critical of, the social movements of our day, calling them "pseudo-religions," and rattled off a laundry list of condemnatory epithets, ending with the observation that the movements for social justice are "also Pelagian, believing that redemption can be accomplished through our own human efforts, without God."

I have to say that anyone who regularly attends meetings of the plutocratic Napa Institute, as Gomez does, should know Pelagianism when he sees it. But to so confidently discern Pelagianism in the Black Lives Matter movement and not among the fat cats at Napa evidences a narrowness of vision I did not previously attribute to Gomez. The source of that narrowness is rooted in the culture warrior blinders Gomez has apparently decided to adopt.

The archbishop's talk is regrettable not only because of its unbalanced and prejudicial content, but in the mere fact of it. Why would a bishop give such a talk? He is not a pundit; he is a pastor.

I have voiced my concerns about wokeness in these pages. There is not a social movement in our time, or in history, about which a social critic should be afraid to raise questions. That is a columnist's job: to question orthodoxies, provoke discussion, to quibble.

It may have been true that Gomez did not choose Chaput decades ago, but he seems to have chosen the Chaput model of episcopal leadership now and that is a shame.

But why would a pastor think those are tasks appropriate to his station, still less to his ministry? If he wants to give a learned, thoughtful criticism, that is one thing, but this trafficking in caricatures and generalizations is beneath the dignity of a bishop. This is the sort of thing we came to expect from Archbishop Charles Chaput, not from Gomez.

In 2004, when Gomez, then an auxiliary bishop to Chaput in Denver, was named archbishop of San Antonio, I remember being concerned that a protégé of Chaput's had been catapulted to such a prestigious post. A Latino priest friend warned me against jumping to any conclusion. "Remember, Chaput chose him," my friend said. "He did not choose Chaput." He thought Gomez was more of a pastor than a culture warrior, and I thought so, too.

Until recently. First, it was the bishops' conference working group to cope with having a Catholic in the White House. Then it was the foolish idea of drafting a document on eucharistic coherence. Now this profoundly regrettable speech.

It may have been true that Gomez did not choose Chaput decades ago, but he seems to have chosen the Chaput model of episcopal leadership now and that is a shame. It diminishes his ability to pastor the souls of his diocese and makes the task of building consensus within the U.S. bishops' conference well-nigh impossible.

The Catholic Church in this country needs the leadership of pastors, not pseudo-pundits, still less culture warriors. It needs bishops who will let themselves be renewed by the documents and the spirit of the council St. Pope John XXIII convoked. It needs Gomez to rediscover his pastoral sensibility. Reading that dreadful speech, it is hard to imagine Gomez rising to the occasion.