(Unsplash/Hannah Busing)

For some readers, Jonathan Franzen's one-word novel titles signal that he is a storyteller who wants to handle big themes. For readers who already find him aloof and arrogant, even bombastic, the big-theme titles probably reinforce this characterization. Other readers, however, may be drawn to his novels precisely because they take aim at perennial questions, often from small and unlikely places: from messy Midwestern family homes, from the small uncomfortable pits of failed marriages, from isolated cabins of eccentrics who have ducked out of the world and its problems.

Still other readers may resist being hauled back into the world of middle-class white Americans, a demographic which has already had plenty of time on center stage.

In Jonathan Franzen's latest novel, Crossroads, middle-class Christian white Americans take the stage. And unlike Franzen's previous big-theme novels, there's no detour to visit arms dealers in Eastern Europe, or hackers in South America. This is appropriate to the tenor of the United States in 2022, when it is dawning even on the most naive that we don't need to import exotic disaster from overseas. We have always been great at manufacturing the homespun variety.

The big theme in Crossroads is "what does it mean to be a good person?" As with Franzen's earlier novels The Corrections and Freedom, the story focuses on the fragile status of a dysfunctional Midwestern family. In this case, the dramas of the family, the Hildebrandts, are all tied to the life of the church where the father, Russ Hildebrandt, is associate pastor. Russ, a handsome, middle-aged liberal, was involved in the civil rights movement in the past and, predictably, had what he regarded as a religious experience while playing white savior on a Navajo reservation. But Russ' coolness has passed its sell-by date. He's been humiliated in the church youth group and supplanted by a younger pastor. Russ is also unhappy in his marriage to Marion.

While Russ is almost painfully transparent in his motives and character, to the point that the reader is perpetually mortified on his behalf, Marion is complex and sly. Her self-lacerations are also more interesting, and more honest than Russ' are. To the outward observer, including her dissatisfied husband, she is simply an overweight and joyless woman with bad hair and bad fashion, someone clearly consumed in her maternal duties, someone to write off.

But in a story where everyone has something to hide, Marion has the most. She too was once fervently religious, but also obsessively sensual. Her youthful ardor and sensuality made her vulnerable to the predatory and dehumanizing forces lurking under the pleasant veneer of 1950s culture. She has had an affair and an abortion. She is a rape survivor. She spent months in a mental institution. And her earnest, superior husband knows none of this, until Marion reaches her spectacular breaking point and lets everything rip.

Advertisement

While Russ and Marion have their "crossroads" moment, so do their three older children, who are absorbed in figuring out their own identity in three disparate modes of rebellion. Their oldest, Clem, becomes convinced he has to enlist and go to Vietnam, to even out the imbalanced scales of racial and social justice that favor him. Their daughter Becky, the perfect one, rebels by joining the youth group where Russ is an outcast. And their brilliant teen son Perry succumbs to an addiction that will precipitate the central crisis point for the whole family.

In Franzen's earlier novels, too, main characters were confronted with "crossroads" moments, in which they must decide who they are going to be. In this novel, that crossroads moment is presented as laden with spiritual and religious significance. The title alludes not only to the hip church youth group where much of the plot unfolds, but also to the story of blues musician Robert Johnson, who according to legend sold his soul at the crossroads in exchange for his musical genius. Russ (again, predictably) is a huge blues fan and lends his Johnson records to the attractive widow he is pursuing, only partially behind Marion's back.

So, is this a story about selling your soul, about salvation or damnation? Not exactly. But it is a story about people for whom questions of salvation and damnation are of utmost importance.

(Unsplash/Jesus Loves Austin)

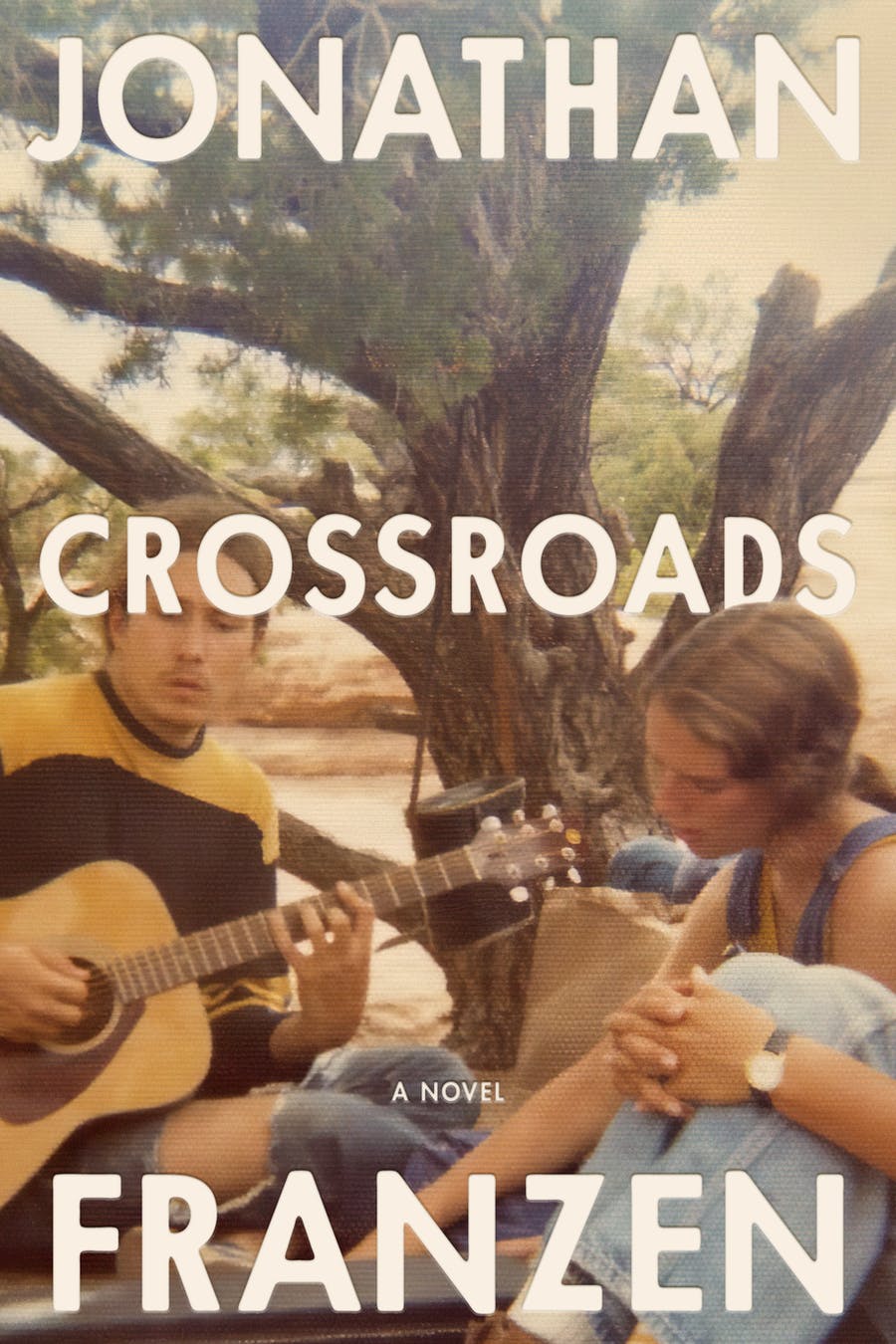

Religion, in Crossroads, is portrayed as a personal, rather than a political force. To the contemporary reader, whether religious or not, it may feel almost quaint to encounter religion as something to be grappled with on an intimate personal level, not in national or even global disputations. Franzen takes us back to a 1970s world of optimistic, progressive Protestantism, of hip youth groups and guitars and charismatic youth pastors.

Anyone who grew up in that uniquely American Christian culture will recognize the brand. And will probably have complex feelings about it. Crossroads is peppered with vignettes that capture the distinct ingredients of that culture, the cringiness, the sincerity, the ecstasy and the confusion.

For instance: early in the novel Russ goes on a charitable visit to a Black church. He takes with him the attractive widow, Frances, whom he hopes will become more involved in his church and his religious work. He also hopes Frances will get more involved with him. Technically, these two desires should be mutually exclusive but in Russ' world they are intertwined. He goes into the basement of the Black church to help install a new water heater and asks Frances to give him a hand, looking forward to her watching him work, to her seeing "how strong he was, how good with tools."

But it's not hypocrisy. He's not playing up charitable work and spiritual leadership just as a seduction ploy. Seduction is part of a larger equation, in which one's relationship with God, even one's guilt before God, one's destiny in service to God, can't be separated from other desires: for approval. For glory. For sex.

It's a muddle familiar to anyone who has participated in that culture. Catholic readers may not have experienced the Protestant youth culture depicted in the novel, but many probably experienced a similar milieu, especially in the charismatic movement. They will recognize the vibe of the Crossroads youth group meetings, where it is almost impossible to parse out how much of the spiritual intensity is authentic, how much is ordinary adolescent crisis, and how much is performative, in an atmosphere where being extra fraught and extra public about it gets rewarded. The reward might come as praise and approbation from the youth pastor — the cool one.

(Unsplash/John Price)

Franzen's earlier novels touched on the power of "youth culture" as well as the lines dividing young adults on the crest of fashion from older ones struggling to keep up, but in Crossroads, the fashion that the younger generation pursues, and the hip pastor cultivates, is a religious fashion, having to do with speaking hard truths and exposing one's most raw emotions.

This doesn't mean the intense and solemn questions the teenagers ask one another about life and God and being a good person are fake. It's just that they are juxtaposed against sexual desire, anger at one's nemeses, frustration with one's own inadequacies, and the pressing need to win praise and approval. Religion is not rendered invalid simply because it's the arena in which perennial and often unworthy human impulses have their way. Nor, however, does it become the cure for these impulses.

Crossroads is the first in a trilogy, and Franzen fans may be curious to see whether the subsequent novels will follow the development of 1970s Christianity, with its emotive displays, earnest good works, and guitar-strumming heartthrobs into the mess of politics and factions in which contemporary progressive Christians find themselves entangled. Overly earnest youth groups with their poorly enforced boundaries and questionable psychological manipulations seem almost endearing, looking back from the standpoint of 2021, when several major movements in several major Christian denominations have become the spiritual arm of fascism.

But the novel also reminds us why religion, for good and for ill, is so potent a historical force. It reorients us to seeing religion as one of the areas in which humans seek fulfillment. What happens at the crossroads may not save us or damn us, but it goes a long way towards making us who we are.