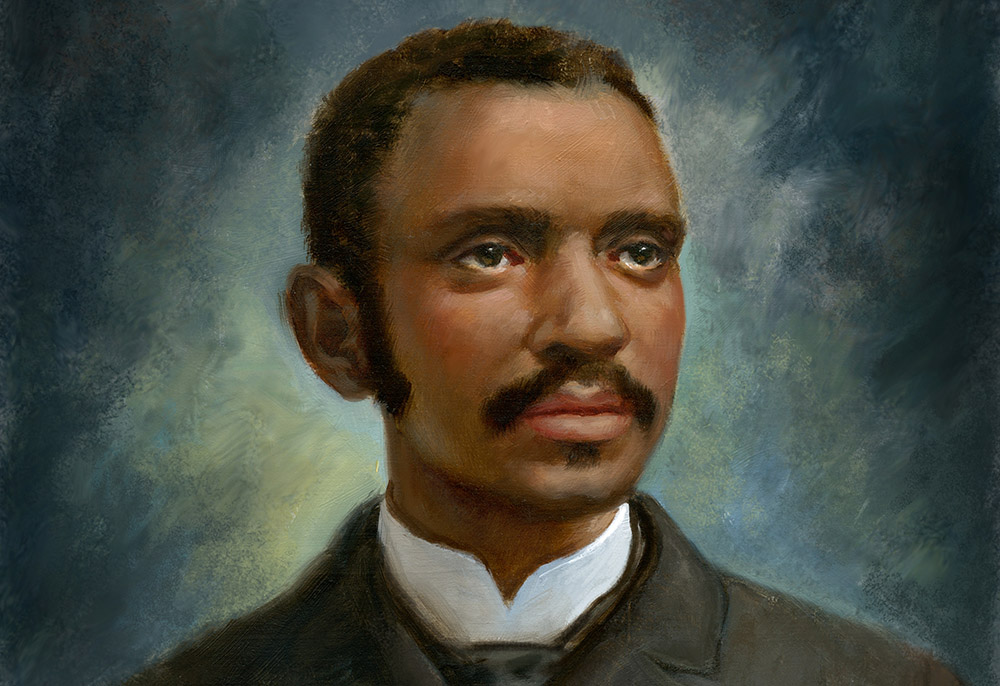

Daniel Rudd (1854-1933), who published the first black Catholic weekly newspaper in Cincinnati, the American Catholic Tribune, is portrayed in an undated painting. (CNS/Courtesy of National Black Catholic Congress)

Earlier this year, a former plantation in Bardstown, Kentucky, named Anatok, was demolished. It was the birthplace of Daniel Rudd, who had been born into slavery at the plantation, and who went on to start the nation's first Black Catholic newspaper, the American Catholic Tribune. A report about the demolition in the Black Catholic Messenger by Nate Tinner-Williams noted the effort to raise funds to restore the property had fallen short, and that a protracted legal battle over the historic building had begun in 2012, "shortly after the release of the first Rudd biography."

A few weeks later, a dear friend in Louisville sent me that biography, A Cry for Justice: Daniel Rudd and His Life in Black Catholicism, Journalism, and Activism, 1854-1933 by Gary B. Agee, who is currently a seminary recruiter and church relations specialist at the School of Theology and Christian Ministry at Anderson University in Indiana.

The book provides a detailed look at Rudd's fascinating life and career, one that is thoroughly researched and carefully explained.

And Rudd's life fascinated. Born into slavery, he was introduced to Catholicism at the Proto-Cathedral of St. Joseph, which was adjacent to the plantation. Bardstown was one of the nation's earliest dioceses, erected in 1808 at the same time Boston, New York and Philadelphia were erected as dioceses. In 1841, the seat of the diocese was moved to Louisville, which had overtaken rural Bardstown as the fastest-growing city in the commonwealth.

The interior of the Proto-Cathedral of St. Joseph in Bardstown, Kentucky, photographed in 1934 (Library of Congress)

Rudd would later recall that he was baptized "at the same font where all the rest, white and black were baptized without discrimination except as who got there first. At confession all knelt in whatever order they came and waited their turn to relieve their sin burden."

When emancipation came in 1865, Rudd's older brother, Charles Henry, moved to Springfield, Ohio, and Daniel followed sometime before 1876. The future journalist worked first at the G.S. Foos Company, which manufactured "hardware and specialties."

It was in Springfield that he began advocating for racial justice as a writer. In 1885, he started his own newspaper with his business partner James Whitson, and the following year the two moved to Cincinnati, where they received the blessing of Archbishop William Henry Elder.

Rudd's early advocacy was akin to that of other Black activists for racial justice, but his newspaper allowed him to explore a specifically church-centered advocacy. The newspaper allowed him to speak to fellow Black Americans about the Catholic Church, and to Catholics about Black Americans.

The cover of "A Cry for Justice: Daniel Rudd and His Life in Black Catholicism, Journalism and Activism, 1854-1933" by the Rev. Gary B. Agee (CNS)

"I have always been a Catholic and, feeling that I knew the teachings of the Catholic Church, I thought there could be no greater factor in solving the race problem than that matchless institution whose history for 1,900 years is but a continual triumph over all assailants," he said in an interview.

As Agee notes, this was the late 19th century and the "Romantic apologetic for Catholicism" influenced many thinkers, including Rudd. This apologetic expressed itself in many ways — for example, the revival of Gothic architecture for church construction. For Rudd, the effects were intellectual.

"Those espousing this hermeneutic for reading history looked with confidence to the civilizing effect of the Catholic Church," Agee writes. "They believed it had been, and would continue to be, the principal ameliorating force in society."

Rudd thought this ameliorating force would be especially critical to any effort to achieve racial justice. He wrote, "The great church of our Lord and Savior is quietly pursuing her divine mission, to 'teach all nations,' placing the seal of her approval at all times upon Justice and equity and condemning in all seasons the injustice heaped upon the poor and despised Negro."

He believed that "the Whole Christian Religion is based on the unity of the Human race. Destroy this and fundamental laws are swept from existence. The Catholic Church has always taught this truth and by that teaching has made present civilization possible."

Powerful prelates endorsed the cause of racial justice, despite the nation's having abandoned Reconstruction and despite the adoption of Jim Crow laws in many states, and Jim Crow practices in many others.

No prelate was more prominent than Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota. The fiery prelate — his nickname was "the consecrated blizzard of the Northwest" — was the most outspoken proponent of full legal and social equality for Black Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At a time when some supported full civil and legal equality among the races but resisted what was then called "amalgamation," or full social equality including interracial marriage, Rudd reprinted Ireland's many sermons on racial issues in the American Catholic Tribune.

'Though Rudd remained a Catholic until his death in 1933, he was let down by his church and its leaders.'

—Gary B. Agee

Starting a newspaper, of course, was not simply an editorial endeavor but a business one as well, and Rudd developed three primary sources of revenue. Rudd printed "custom made cards, letterheads, envelopes, bill heads, statements, pamphlets, books, briefs and 'all kinds of legal and commercial work,'" in addition to his newspaper. Secondly, the newspaper was popular, and Rudd employed five traveling agents to sell subscriptions.

Thirdly, Rudd received contributions from many white Catholics, and even a few Protestants, who saw the value of his work. The legendary French Cardinal Charles Lavigerie, archbishop of Carthage and Algiers, was so impressed by Rudd when the two met in 1889 in Switzerland that he donated 1,000 francs per year for the rest of his life.

Agee's biography examines the different issues that Rudd addressed in the pages of his newspaper, and how Rudd's own views about the best means for achieving racial justice developed over time. Agee also looks at how competition and other factors led to the decline in readership and eventual closure in 1897, by which time Rudd had moved to Detroit.

Advertisement

Rudd relied not only on journalism to achieve his goals. He was the driving force behind the Colored Catholic Congress movement, which held its first meeting in Washington, D.C., in 1889. Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons, who was the primate of the U.S. church in fact though not in name, delivered the opening sermon.

This was an era of such congresses. For example, the German Central Verein organized German-American Catholics (and invited Rudd to speak at one of their congresses). T. Thomas Fortune founded the National Afro-American League in 1887.

These congresses were meant to create networks for advocacy and to recruit and train leaders capable of advancing the interests of the group. They also served to collect information about diverse local conditions. In advance of the third meeting of the Colored Catholic Congress, in Philadelphia, delegates were invited to furnish answers to key demographic questions:

What is the estimated Colored population of your city or country? What is the estimated Colored Catholic population? How many children attending Sunday School or Catechism classes? How many Catholic schools in your city? How many children attending Parochial School? What faculties are there for the education of boys over twelve years?

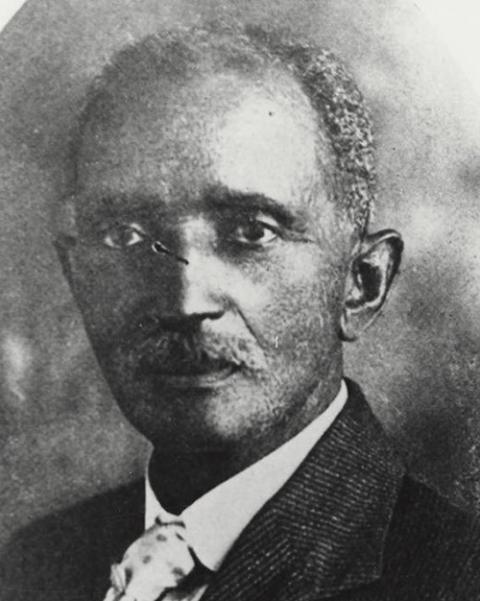

Daniel Rudd, circa 1915 (Central Arkansas Library System)

The movement, like the newspaper, did not last, but Agee shows how indomitable Rudd's belief in the central place of the Catholic Church in achieving race relations could and should be, even if that belief became increasingly hard to justify.

Agee writes, "Though Rudd remained a Catholic until his death in 1933, he was let down by his church and its leaders. Sometime after the collapse of the ACT, Rudd looked elsewhere for a more promising path forward. In his later life, he promoted a prescription for racial uplift that closely resembled Booker T. Washington's economic self-help approach."

Additional chapters of this fine book deal with Rudd's attitudes toward other oppressed minorities, his editorial reactions to the increasingly hostile legal and social environment faced by Blacks, exemplified by the increasingly prominent practice of lynching, and Rudd's later years in the South.

By the end of the book, the reader has a real sense of who this man and how remarkable and distinctive his life's work was. Occasionally, the prose gets bogged down and Agee has a tendency to frame a quote by repeating it, but these are small complaints compared to the work's achievement.

The life of this fascinating Black Catholic leader and activist is one that would interest all Catholics, and hopefully challenge us, too, to be as committed to a Catholic vision of racial equality as was Daniel Rudd.