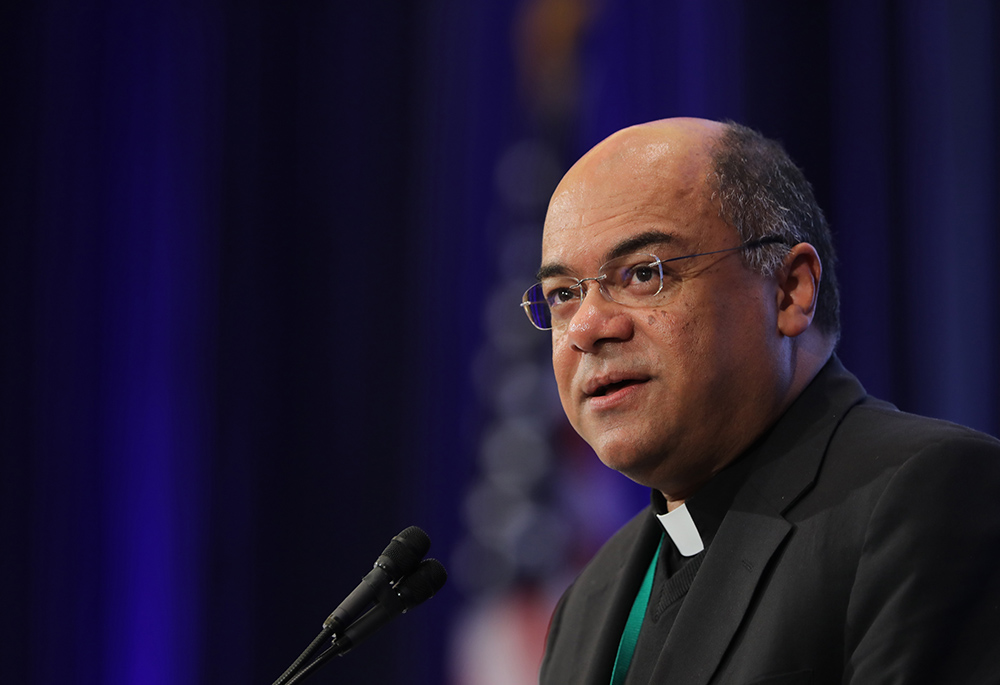

Bishop Shelton Fabre of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana, speaks during the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops Nov. 13, 2019, in Baltimore. Pope Francis named Fabre as the new archbishop of Louisville, Kentucky; the announcement was made Feb. 8. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Archbishop-designate Shelton Fabre's appointment as the fifth archbishop and 10th bishop of the historic see of Louisville reverberates beyond what would be usual for a diocese of 180,000 Catholics. For a variety of reasons, it shows the degree to which the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in the United States is finally, however slowly, being brought into sync with the agenda of Pope Francis.

The most significant thing about Fabre's resume is what is not there: He never had a desk job in Rome. The Francis revolution is not, as some suggest, an ideological revolution but an anti-ideology revolution. It is about appointing and promoting bishops with pastoral experience, not a network of Roman connections. Fabre served in several Baton Rouge parishes and as a chaplain at the state penitentiary before being named an auxiliary bishop in New Orleans in 2006. In 2013, he was named bishop of Houma-Thibodaux, a poor, rural diocese south of New Orleans.

Of the 13 U.S. archbishops named by Pope Francis, only four had experience working in Rome. Two of those, Archbishop Michael Jackels of Dubuque, Iowa, who once worked at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and Archbishop Leonard Blair of Hartford, Connecticut, who worked at the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs of the Holy See, were named in 2013, when Francis had not yet removed Cardinals Raymond Burke and Justin Rigali from the Congregation for Bishops. Archbishop Bernard Hebda, named to St. Paul-Minneapolis in 2016, once worked at the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, but it was his time as Cardinal Donald Wuerl's secretary and his reputation as an excellent canonist that got him sent to Minnesota. And Cardinal Joseph Tobin once served as Secretary of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, but his tenure was cut short and he was famously transferred to Indianapolis in 2012 before being named a cardinal and promoted to Newark in 2015.

The Francis revolution is not, as some suggest, an ideological revolution but an anti-ideology revolution.

The other nine archbishops appointed by Francis — Archbishop Andrew Bellisario of Anchorage-Juneau, Alaska; Archbishop Gregory Hartmayer* of Atlanta; Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago; Archbishop Charles Thompson of Indianapolis; Archbishop Nelson Pérez of Philadelphia; Archbishop Mitchell Rozanski of St. Louis; Archbishop John Wester of Santa Fe, New Mexico; Archbishop Paul Etienne of Seattle; and Cardinal Wilton Gregory of Washington, D.C. — none of them ever worked at a desk in Rome.

Indeed, with Pope Francis, the church's culture has shifted in the direction opposite of that found in the secular culture. If secular, cultural trends start on the coasts and work their way into the heartland, the remaking of the U.S. Catholic Church began with the appointment of Cupich to Chicago in 2014, and it is in the center of the country — St. Louis, Indianapolis, and now Louisville, Santa Fe — that the change is most evident.

Appointments to metropolitan sees made by previous popes relied heavily on Roman connections. Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York was the rector of the North American College. Archbishop Allen Vigneron of Detroit worked in the Vatican Secretariat of State. Galveston-Houston Cardinal Daniel DiNardo worked at the Congregation for Bishops. San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone worked at the Apostolic Signatura.

In addition to a Roman resume, these are not the names that leap to mind when you think of bishops who are enthusiastic about Pope Francis.

Advertisement

In addition to a commitment to pastoral ministry, it is worth noting Fabre's work leading the U.S. bishops' conference Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism as they drafted their 2018 pastoral statement "Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love." He displayed a deft skill balancing the need to be blunt about the enduring moral sin of racism with an awareness of what he could get his brother bishops to approve. Louisville has a large Black population that is still mourning the killing of Breonna Taylor, and still angry at the failure to prosecute her killers.

A commitment to the environmental vision of Laudato Si' has not been optional for the new archbishop. Fabre's previous Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux was wrecked by Hurricane Ida last summer. Rising sea levels put cities like Houma at great risk of serious flooding in the years to come. The Surging Seas risk finder predicts Houma has an 89% chance of having at least one severe flood over 6 feet before 2050. In his new assignment, Fabre will be able to work with one of the most interesting environmental projects in the nation, the University of Louisville's Envirome Institute.

Some people forget that Louisville is such an historic see. It was established in 1808 by Pope Pius VII at the same time that the dioceses in Boston, New York and Philadelphia were created. Only Baltimore and New Orleans are older, and New Orleans was still part of the Spanish empire when it became home to the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas in 1793. Originally based in Bardstown, the first bishop, Benedict Joseph Flaget, relocated the see to Louisville in 1841, although Bardstown is still home to the proto-Cathedral of St. Joseph.

The cathedral in Louisville experienced a renaissance in the 1980s and 1990s under the leadership of legendary pastor Fr. Ron Knott, Archbishop Thomas Kelly and the Cathedral Heritage Foundation, now the Center for Interfaith Relations. It was not so much a renovation of the cathedral, still less a "restoration," the word preferred by traditionalists wanting to turn the clock back. It was a revitalization, fully in line with the vision of Vatican II that the church should be a sacrament in the world. They understood the primary goal was not merely repointing bricks but bringing new life to the ministries housed in the parish, serving the needs of Louisville's inner city. Under Knott's leadership, the parish community at the cathedral grew from 150 households to 1,350 households in just under 12 years, while launching a variety of ministries to the city's poor and marginalized.

This is only part of the legacy that welcomed Archbishop-designate Fabre yesterday (Feb. 8) to the beautiful city of Louisville. His selection is a hopeful sign for the Catholics and non-Catholics of that city. It is a hopeful sign for the whole church in the United States.

*This story has been updated to correct Archbishop Gregory Hartmayer's first name.