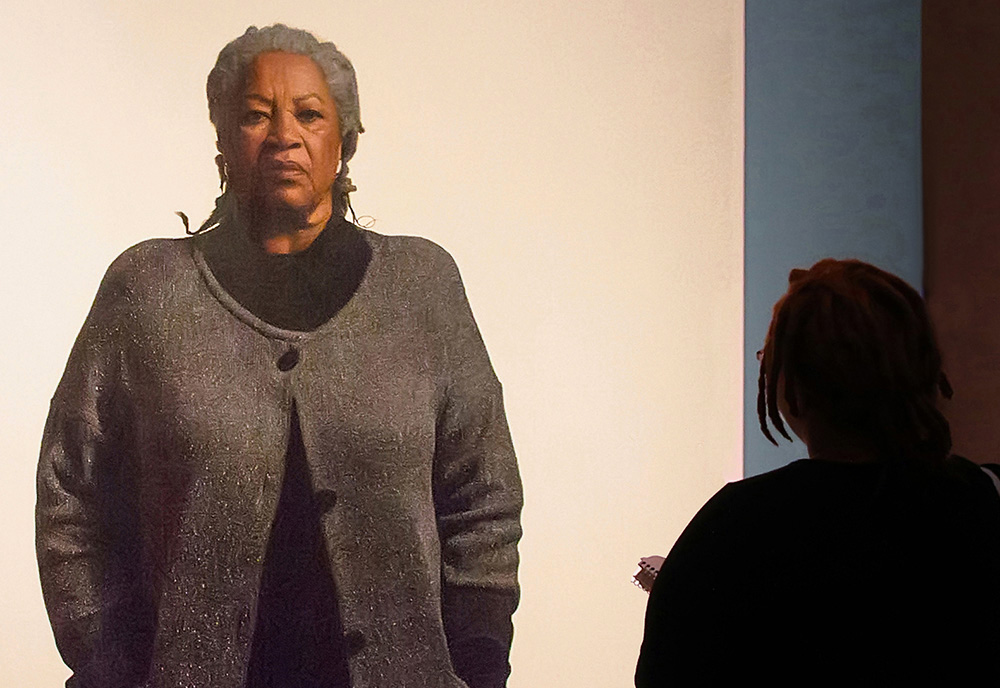

A painting of author Toni Morrison, by artist Robert McCurdy, is viewed during the "20th Century Americans: 2000 to Present" exhibit at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (Dreamstime/Mira Agron)

Excerpt reprinted with permission from Toni Morrison's Spiritual Vision: Faith, Folktales, and Feminism in Her Life and Literature by Nadra Nittle © 2021 Fortress Press.

Toni Morrison's Paradise was the first book she published after winning the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature for a body of work that "gives life to an essential aspect of American reality." This honor, along with the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction she won for Beloved and the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award she won for Song of Solomon, cemented Morrison's status as one of the world's preeminent writers. But after Paradise debuted on Christmas Eve 1997, Morrison recognized that her many accolades wouldn't prevent critics and scholars from dismissing her seventh novel. After all, she said, the book is "about this unimportant intellectual topic, which is religion."

Paradise takes place (mostly) in the 1960s and '70s in the fictional all-Black town of Ruby, Oklahoma, established by nine families who in 1890 went on to found yet another all-Black town — Haven, Oklahoma. Ninety miles away from any other municipality, Ruby is a seemingly Black utopia where there's no crime, drugs, death, or television, and women can take midnight strolls without fear of harm. But Ruby is far from perfect: families adhere to a narrow and dogmatic interpretation of Protestantism and maintain racial purity by coupling with only the darkest of African Americans, even if that means resorting to incest.

The townspeople's bigotry doesn't stop at colorism, for Ruby's male leaders develop an irrational hatred for the group of women who live in the "Convent" on the outskirts of their community. First an embezzler's mansion, which was then turned into a Catholic boarding school for Arapaho girls, the Convent has become an unofficial home for troubled and traumatized women — among them a sexually exploited former foster youth, a mother who leaves her infant twins to suffocate in a hot car, and a poor little rich girl who runs off with her high school janitor. In the care of the spiritually gifted Consolata Sosa, an informal reverend mother, the Convent women find empowerment. Suspecting them of everything from lesbianism to witchcraft, however, Ruby's men ambush the Convent women one day in 1976 to blot out the evil they claim they represent. "God at their side, the men take aim. For Ruby," the narrator states. By carrying out a massacre, the men introduce the sin and crime they detest in the outside world into their paradise.

"Good intentions are distorted in some way so that they become ungenerous," Morrison explained of the ambush. "Now the community becomes that terrible thing, the chosen people ... chosen to exclude somebody else. The notion of paradise as exclusive is what troubles me."

The idea to write Paradise came to her when she visited Brazil in the 1980s and heard a story, later proven false, about Black nuns who routinely took in abandoned children. Despite their good works, a group of men murdered them for practicing Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religion that blends Yoruba spirituality with Roman Catholicism. "I've since learned it never happened," Morrison told The New York Times in 1998. "But for me it was irrelevant. And it said much about institutional religion and uninstitutional religion, how close they are."

The all-Black towns that free people of color established in states such as Oklahoma and Kansas during Reconstruction also influenced the book. In his 1998 review of Paradise for Salon, Brent Staples surmised that Morrison's Ohio upbringing exposed her to these settlements because one such town, Langston, Oklahoma, took its name from Ohio's first African American lawyer, John Mercer Langston — an Oberlin College graduate, Reconstruction congressman, and great-uncle of Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes. About two thousand African Americans settled in Langston, but the population dwindled when they ran out of money and could not otherwise earn a living. So the town's founders resettled in Guthrie, Oklahoma, just as the Haven residents relocate to Ruby in Morrison's novel.

Advertisement

Infused with what one critic described as a "magico-Christian message," Paradise is hardly just historical fiction. The book opens with an epigraph quoting "The Thunder, Perfect Mind," a poem from the collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts found near the Egyptian town Nag Hammadi in 1945. Sometimes labeled a Gnostic myth, the poem dates back to the second or third century and is told from the point of a view of a female deity. Historian Elaine Pagels, author of The Gnostic Gospels, has described the work as "strange" and "marvelous." She said,

It speaks in the voice of a feminine divine power, but one that unites all opposites. One that is not only speaking in women, but also in all people. One that speaks not only in citizens, but aliens, it says, in the poor and in the rich. It's a poem which sees the radiance of the divine in all aspects of human life, from the sordidness of the slums of Cairo or Alexandria, as they would have been, to the people of great wealth, from men to women to slaves. In that poem, the divine appears in every, and the most unexpected, forms.

Paradise revisits the themes of "The Thunder, Perfect Mind" — the unification of opposites, the divine feminine, and the presence of holiness in unexpected places — again and again. But as Morrison predicted, the book's focus on spirituality earned it some scathing reviews. Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times criticized the novel for its "gratuitous biblical allusions," which included "comparing the story of Ruby's founders to the story of the Holy Family, turned away from the inn." Zoë Heller of the London Review of Books argued that the book's message wasn't morally ambiguous enough, noting that "at some point, all Morrison's major novels seem to lose patience with the finicky business of recording moral blur, choosing to swerve off into the realm of moral fable and preacherly uplift." And in Broken Estate, his 1999 book of literary criticism, James Wood objected to the presence of magic in Paradise at all, "since fiction is itself a kind of magic."

Morrison did not feature magical realism in her literature as much as she did the reality of an indigenous African way of being.

This criticism points to a fundamental misunderstanding of Morrison's literary influences and philosophy. While she would likely agree with Wood's assertion that fiction writing is a kind of magic, she did not include magic in her work as a literary device. Its presence in her fiction reflects a pan-African perspective in which the lines between the natural and supernatural worlds converge. The dead coexist with the living, signs foretell the future, and healing does not occur in a doctor's office. In short, Morrison did not feature magical realism in her literature as much as she did the reality of an indigenous African way of being. And in the mold of the Black oral tradition, her works have a moral core because African American storytellers serve primarily as teachers who impart life lessons to community members, particularly the young.

In her work, biblical allusions reflect the Scripture-laden speech of real-life Black Americans, who passed down Old Testament stories just as they did folklore about flying Africans. Having historically only the church as a refuge from an outside world bent on demeaning and destroying them, Black Americans have always identified with biblical figures, especially those who suffered injustice and ill treatment. This history, not gratuitousness, informed Morrison's decision to compare Paradise's characters to those in the Bible — notably Eve, the Israelites, and the Holy Family. In "The Master's Tools: Morrison's Paradise and the Problem of Christianity," Shirley A. Stave argues,

Morrison very consciously parallels the biblical exodus of the Israelites with the post-slavery wilderness wandering of a group of "eight-rock" families seeking to establish an all-Black community removed from the sites of the oppression. Specifically, the text mirrors the divine intervention central to the original exodus, in which Jahweh's chosen people are led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night; here, the founding families are led to Haven by a mysterious small man visible only to the group's leader, his son, an occasional child. Summoned ... through a night of prayer that recalls Christ's experience in Gethsemane, the mysterious figure arrives to the sound of thundering, earth-shaking footsteps ... that reverberate again once the wanderers have arrived at their destination and the man vanishes.

Oklahoma thunderstorm (Unsplash/Raychel Sanner)

Morrison found some of the criticism of Paradise to be "deeply, deeply insulting" and even "badly written," but she did not take it personally. She told Salon that critiques of African American and women's literature intrigued her and that significant progress needed to be made to improve responses to such fiction. "I'm not entangled at all in shaping my work according to other people's views of how I should have done it, how I succeeded at doing it," she said. "So, it [criticism] doesn't have that kind of effect on me at all. But I'm very interested in the responses in general. And there have been some very curious and interesting things in the reviews so far."

Since the novel explores subject matter Morrison explored in her earlier works — magic, religion, and misogyny — some of the unflattering reviews Paradise received are particularly perplexing. With a nonlinear chronology, a glut of characters, and points of view that change as quickly as one paragraph to the next, Paradise is a difficult book for readers who don't give it their utmost attention, but it is also familiar territory for Morrison fans. With descriptions of the founding of not one but two towns and the backstory of the Convent, Paradise amplifies Morrison's trademark village literature. As she does in Sula, Morrison complicates the virgin-whore dichotomy, arguing that the archetypes are inextricable from one another. And she uses two healing women of color to share a revelation about Christianity that her previous novels never made completely explicit.

While Paradise doesn't condemn Christianity, it argues that for it to be a tool of liberation, it can't be a reproduction of white religion. It must recognize the cosmologies of people of color and the social conditions that fuel oppression; moreover, it must include the divine feminine. Practicing a rigid and closed form of Christianity, the men of Ruby just imitate their white oppressors, spreading the hatred and intolerance their ancestors fled when they founded Haven. Through the novel's pair of healers, Consolata Sosa and Lone DuPres, the reader learns that a different type of belief system — one that considers an individual's spiritual wisdom rather than religious orthodoxy alone — is necessary for communal transformation, healing, and fulfillment.