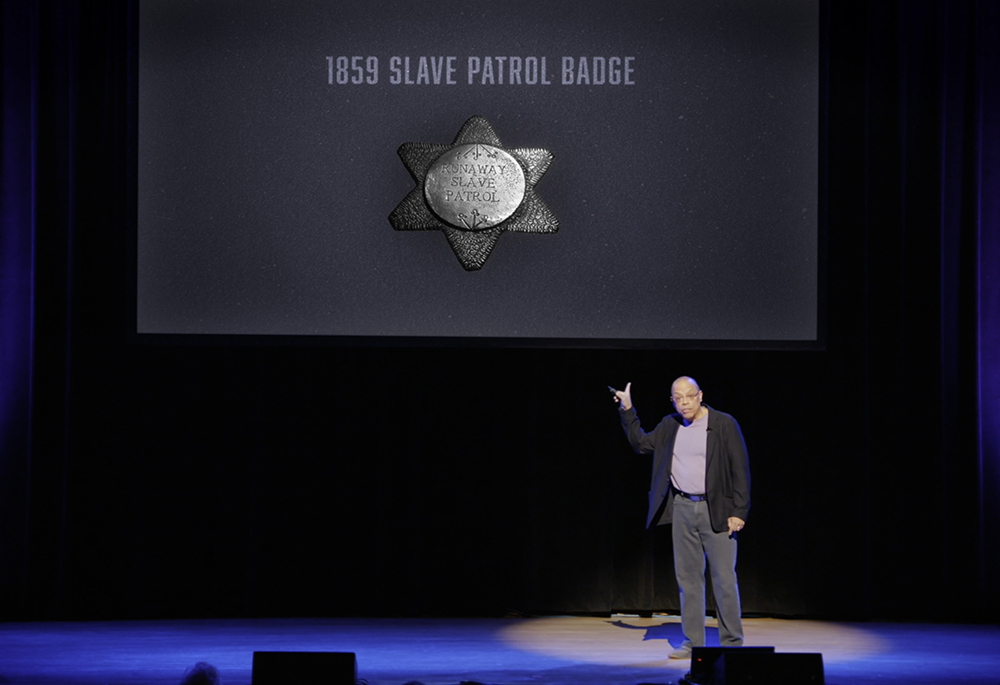

Jeffery Robinson at New York City's Town Hall in "Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Jesse Wakeman)

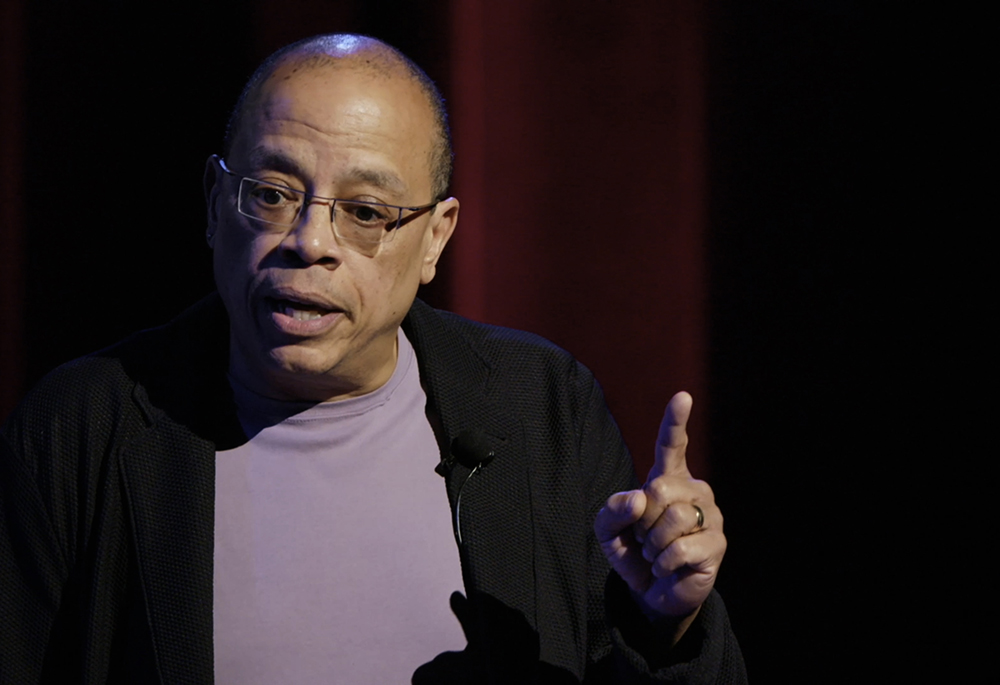

Suddenly becoming guardian of his nephew Matthew Brooks after the death of the 13-year-old's mom in 2011 naturally transformed former ACLU deputy legal director Jeffery Robinson. The Black criminal defense attorney feared what Matthew, as a Black male, would encounter on America's streets.

This fear precipitated the 65-year-old's "deep dive" into American racism. Robinson, Jesuit educated at Marquette University and a Harvard Law School graduate, grew angry and felt ignorant when he "started learning stuff about the history of race in America I had never heard before."

The advocate compiled what he discovered into a persuasive, comprehensive and authoritative presentation on anti-Black racism. The documentary, "Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America," revolves around a Juneteenth talk Robinson gave June 19, 2018, at New York's venerable Town Hall.

Vital and challenging, "Who We Are" was released into theaters in February to coincide with Black History Month. It's now available to stream at Amazon and Vudu. Groups can also request to host a screening at the Who We Are site.

The film is directed by Emily and Sarah Kunstler, best known for their affectionate yet candid portrait of their late father, both beloved and despised attorney William Kunstler, "William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe." The sisters also produced the documentary with Robinson, who wrote the screenplay.

New York may be the talk's setting, but the Memphis, Tennessee, of the speaker's childhood is uppermost on his mind as he presents.

Jeffery Robinson at New York City's Town Hall in "Who We Are" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Jesse Wakeman)

Robinson was 11 years old on March 28, 1968, when his Catholic father, Herbert, took him and his older brother, Herbert Jr., to a march backing the unionization drive of the city's Black sanitation workers.

Until that moment, "to my young eyes we had been on a path to racial justice that was amazing," Robinson says. "There was the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act. We were at a tipping point."

"We could," he says, "roll forward with this momentum for racial justice or we could roll back. Then April 4, 1968, happened, and it felt like the whole thing rolled back."

More than three years ago, Robinson couldn't have anticipated the national reawakening on race that occurred in the summer of 2020 in the wake of George Floyd's murder.

Advertisement

But the attorney seemed prescient when he argued that because "young activists are calling us into account; we have reached another tipping point."

"And the question for all of us in this room," he continues, "is what are we going to do about it?"

Robinson proactively attempts to attenuate the listeners' preconditioned defensiveness. "Slavery," he says, "is not our fault. We didn't do it. We didn't cause it."

"But," he quickly adds, "it is our shared history."

Jeffery Robinson at the "Hanging Tree" on Ashley Avenue in Charleston, South Carolina (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Jesse Wakeman)

White supremacy, Robinson says, was baked into the Constitution, as manifest in the clause that required runaway slaves to be returned to their owners. So important to the framers, the provision couldn't be banned or amended until 1808, almost 20 years after its drafting, Robinson says.

Post-Reconstruction, the attorney details how suppression laws reduced Black voters' ranks from a high of 700,000 in 1868 to 5,000 in 1898. From 1877 to 1950, more than 4,000 lynchings embodied white supremacy, according to Robinson.

Robinson's presentation resembles an outstanding TED talk you'd recommend to your friends, but the road trips he undertakes lend "Who We Are" its texture and resonance.

Robinson meets people such as Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, who was killed by a New York police officer in 2014. Carr describes their connection to Black history, but Robinson, returning to his hometown, most importantly reconciles with his own place in that history.

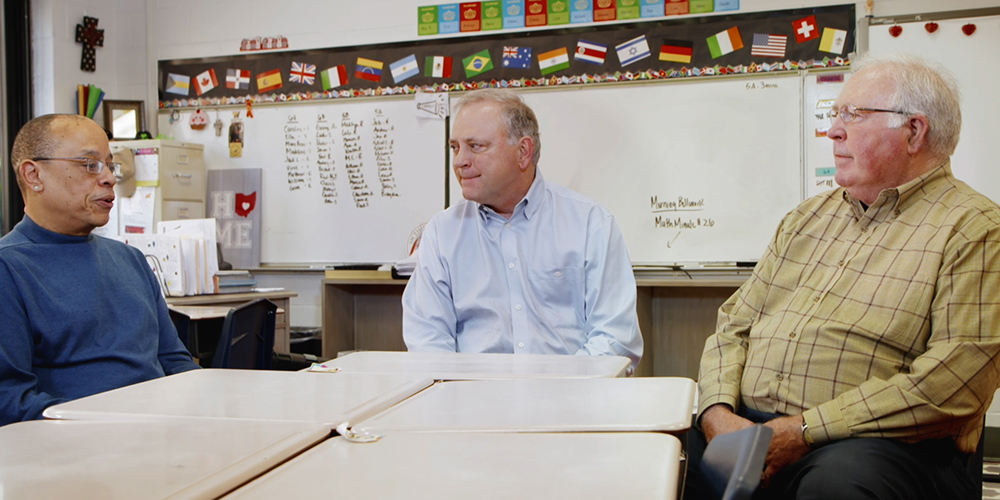

His reunion with his white best friend from St. Louis Catholic School, Robert "Opie" Orians, and Opie's older brother, Richard, is particularly evocative and touching. Robinson and his brother integrated into the school in 1963.

Richard, who coached Robinson and Opie's high school basketball team, tells the story of a game in the Memphis suburb of Walls, Mississippi, when the host school's parents didn't want their kids to play against an integrated team until the school's pastor overruled the parents. Robinson discovers Richard didn't tell him about the parents' reaction to protect him from their prejudice. The revelation palpably deepens the affectionate bond between the trio. Such moments elevate "Who We Are," but it has some flaws.

From left: Jeffery Robinson with Robert Orians and Richard Orians in "Who We Are" (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics/Jesse Wakeman)

Perhaps not wanting to draw unfavorable comparisons to Ta-Nehisi Coates' acclaimed 2015 book Between the World and Me — a raw, searing, protracted epistle to his then 15-year-old son, Samori, about being a Black male — Matthew doesn't appear in the documentary. Nonetheless, hearing about his uncle's influence upon him would have been helpful and interesting.

Also, Robinson updates racism's widely accepted definition of prejudice plus power to racism defined as prejudice plus social power plus legal authority.

It would have been clearer to viewers not familiar with these definitions if Robinson also said that although persons of color can be prejudiced, they can't be considered racist because they lack the power white people possess. Because whites possess power persons of color don't, only whites can perpetrate or benefit from racism.

In that sense, as William Kunstler said to the directors, "all white people are racists." White people can recover from their racism, Robinson suggests, by being mindful of their "white privilege" that understands "you walk through the world differently than Black and brown people."

Despite its defects, "Who We Are" is essential viewing, arriving at a crucial moment when too many deny racism happens.

Be sure to watch through the credits for a joyous rendition of the movement anthem "Woke Up This Morning with My Mind Stayed on Freedom." It's precisely what your spirit needs to do the work that still needs doing.