(NCR graphic; photo: Wikimedia Commons/Jnn13)

If last year began with the hope that normalcy might return, a hope that was often thwarted, this year the politics of the nation are marked by a fear that the signs of decline in the very fabric of our democracy might become dominant. Worse, no one is exactly sure how to combat this threat.

A poll of young people conducted by Harvard's Kennedy School Institute of Politics last autumn found that 52% of those aged 18-29 thought America's democracy was "in trouble" or worse, that ours is a "failed democracy." These are young people!

There was a distinct partisan skewing of the results. Seventy percent of young Republicans thought that democracy was "in trouble" or "failed" compared to 45% of Democrats.

Forty-six percent of young Republicans thought there was an even chance that America would experience a second civil war in their lifetime. Thirty-eight percent of young independents and 32% of young Democrats thought the same.

On climate change, similar divergences arose. Sixty percent of young Democrats said climate change had already impacted their community, and 74% predicted it would impact their own decisions in the future. Only 23% of young Republicans said their community had already experienced the impact of climate change, and 32% agreed it would have an impact on their future decision-making.

The lack of faith in the future of democracy has two components. The most immediate is concern with the way election laws are being changed, mostly by Republican state legislatures, changes that invite abuse of the democratic process. The second problem is that if the government can't deliver on issues like inflation that really matter to people, or issues like climate change, which will really matter, people understandably begin to wonder if democracy really is so valuable.

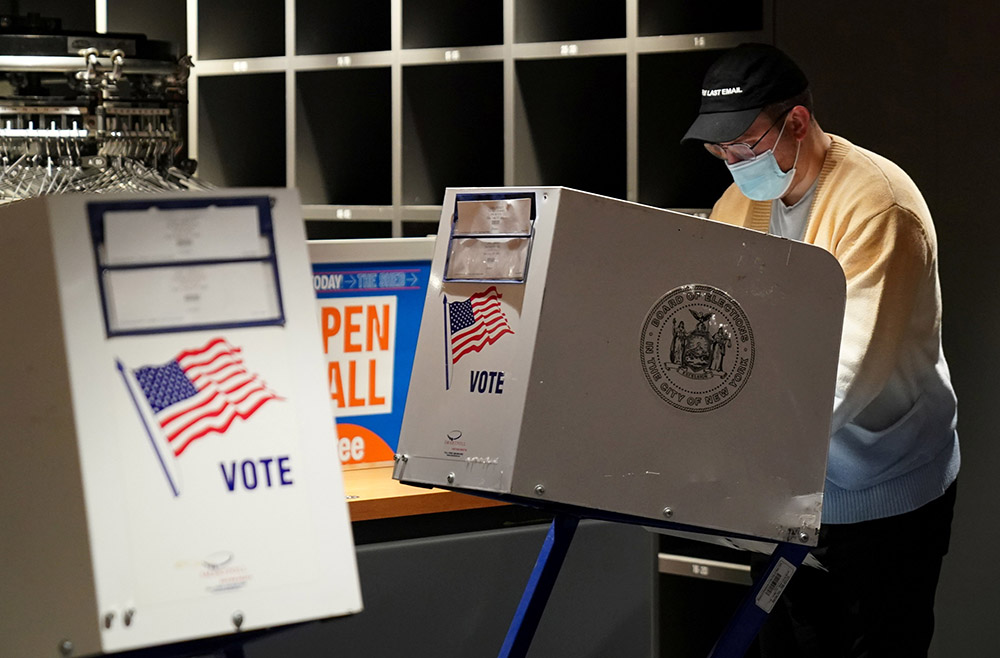

A voter in New York City fills out a ballot at Hudson Yards during early voting Oct. 24, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Bryan R Smith)

What can be done to save our democracy in 2022? We in the media need to continue to shine a light on the challenges to democracy and promote dialogue. "Democracy dies in darkness" has become the official slogan of The Washington Post, but all of us should make it our own.

The decision by eight Republican-controlled state legislatures to shift control over elections from nonpartisan to partisan groups is deeply alarming. Arizona and Georgia are the only two of the eight to be battleground states, but the trend is part of a worrying phenomenon: Republicans at all levels of government are more concerned with power and specifically with fealty to the Trumpian narrative that the election was stolen than they are to the kinds of bipartisan democratic norms that have shaped ours and other successful democracies. How do we counteract this?

In the weeks after the 2020 election, the courts became the primary venue for legal challenges to the election results. More than 40 challenges were filed by President Donald Trump or his political acolytes, but they all failed. The U.S. Supreme Court largely stayed aloof from the proceedings, finally refusing to hear the last challenge to the election results in Pennsylvania in April.

Those court rulings, and the aloof posture of the highest court, upheld the results the 2020 process yielded. If the changed processes yield a "Heads I win, tails you lose" effect in states that now have a partisan process, will the courts defend democracy? The judiciary may be the last, best hope we have to apply the 14th Amendment to defend the simple proposition without which democracy is meaningless: one person, one vote.

There is a further, related question: Will future rulings of the courts be respected? Recently, Sen. Elizabeth Warren advocated expanding the number of justices on the Supreme Court. The commission set up by President Joe Biden was divided about adding justices, but seemed more inclined to support term limits for Supreme Court justices.

People walk past the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington Dec. 1, 2021. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

It is impossible to deny that any effort by Biden to pack the court would have the effect of diminishing the court's authority as an organ of government above partisan politics. The problem is that Sen. Mitch McConnell has, in effect, already packed the court by refusing to consider an eminently qualified nominee, now-Attorney General Merrick Garland, put forward by President Barack Obama.

As law professor Kermit Roosevelt has pointed out, "The concern that Republicans might manipulate the size of the Court for partisan advantage in the future if Democrats do it now overlooks the fact that they've already done it, in the very recent past. Refusing to consider any Obama nominee (and pledging to do the same to Hillary Clinton if she won) is exactly that."

On balance, I side with those who oppose enlarging the court for a simple reason: Three of the justices were appointed by the man who remains the greatest threat to democracy. If they refuse to conspire at any attempts to subvert an election result, it will have greater authority than if an expanded court with three or four new Democratic-appointed justices did the same.

Besides, a court-packing scheme is never going to happen, and Democrats need to make themselves be seen as a party that gets things done.

The Supreme Court's decision in the abortion case Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization will generate a great deal of attention, but it is far from clear what effect it will have on politics in 2022. During last November's elections, both former Gov. Terry McAuliffe in Virginia and Gov. Phil Murphy in New Jersey leaned hard into their support for abortion rights, convinced it would galvanize women voters. McAuliffe lost and Murphy barely won. Other issues like education and taxes predominated.

A family is seen near the U.S. Capitol in Washington Nov. 18, 2021. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Over time, I fear the backlash against overturning Roe will be large and consequential, but not necessarily in 2022.

As the year ended, and all eyes in Congress turned to the midterms, the prospect for the Democrats is grim. Historically, the party that controls the White House loses seats in the midterms, and the slim Democratic margin in the House means that they are likely to lose their majority. That has become a self-fulfilling prophecy as 20 Democratic incumbents have announced plans to retire, compared to only 11 Republicans. Add to that the effects of highly partisan gerrymandering and it is hard to see how the Democrats could maintain control of Congress.

Consequently, the Democrats desperately need to get back to passing some of the key elements of Biden's Build Back Better plan. Sen. Joe Manchin is a problem to be sure. He insists that he is a fiscal conservative and always has been, but the only path for Democrats to become a majority, governing party is to embrace progressive economic ideas and more moderate social ones.

Back in 2019, I called attention to research by political scientist Lee Drutman that demonstrated pretty conclusively that less than 4% of voters fit the profile of moderation articulated by Manchin while 28% are socially moderate and economically progressive. If the Democrats want to change the trajectory they are on, they should make sure Manchin gets a call every morning from Biden, followed by a sit down with Drutman!

Manchin is not the only problem facing the Democrats. There are plenty of others who want the party to lead with hot-button cultural issues. Fights over the way race and gender issues are taught in the schools and regulated in society will not play out well for the Democrats until they free themselves from the demands of the left's cultural avatars.

For example, conservative media has been intensively covering the story of Lia Thomas, a transgender swimmer at the University of Pennsylvania who has broken a host of women's swimming records, and done so by exceedingly large margins. There is nothing about the story at The New York Times or The Washington Post.

Former Olympic champion Nancy Hogshead-Makar, while voicing support for allowing transgender athletes to compete, and showing evident concern for the plight of those confronting gender dysphoria, nonetheless said such participation could only be fair if "these individuals can show that they've mitigated the athletic advantages that come with male puberty."

Advertisement

Hogshead-Makar added, correctly, that Thomas' "domination of the 'women's sports' category is doing nothing to engender greater empathy for inclusive practices throughout society for the trans community."

Democrats need to find ways to advocate for transgender rights while also recognizing the legitimacy of concerns about the integrity of women's sports. Those who insist on overturning traditional ideas about the significance of gender and sex need to own the degree to which their own extremism helps elect Republicans.

Similarly, the left needs to find ways to discuss the teaching of American history that does not cover up the nation's sins, but which also does not buy into ideological narratives that articulate an exceedingly hostile account of the nation's past. There is a revolution afoot in school board elections, and Democrats need to creatively defend teaching the truth about history while putting Republicans on the defensive for the extremeness of their own demands.

But Democrats will not get there if they question why parents should have any say over what their children are taught in schools, as McAuliffe did during his failed campaign and as "1619 Project" creator Nikole Hannah-Jones did on "Meet the Press" just last week.

Parents and community members in Ashburn, Virginia, attend a Loudoun County School Board meeting June 22, 2021, which included debate over "critical race theory" in the school curriculum. (CNS/Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

Discussions of race are always fraught in American life, not just when it comes to education. While it is morally necessary to address the ongoing, pernicious effects of racism, buying in to some of the more extreme voices on the issue will doom Democrats.

For example, Republican gains among Latinos are rooted in large part in the distaste many Latinos have for highly negative assessments of the country coming from the left. First and second-generation Latinos know their parents or grandparents struggled mightily to reach this country. If you aspired to come to America, you do not respond well when people tell you it is a hot bed of hypocrisy and racial animus.

What is more, many Latinos — and many Black voters — are not as culturally liberal as the academic talking heads that present themselves as spokespersons for their communities in the media.

Finally, there is the pandemic. Americans are tired of coping with it but the virus is indifferent to our emotions and attentive to our physical vulnerabilities. Until the virus is largely spent, Biden will be incapable of delivering on his No. 1 campaign promise: a return to normalcy. If we can round the corner on the virus, and if the administration and, especially, the Federal Reserve can tame inflation while the gains in wage levels remain, Biden's approval ratings and the Democrats' prospects could rebound quickly.

There is a fringe group of Americans who detest Biden, but most Americans don't. The president embodies a pragmatic political approach that has served our nation well but that has been failing to deliver for the American people in recent decades. If he can make progress on infrastructure, child care and climate change — and the pandemic is in the rearview mirror — the resilience of American democracy might be the leading story of 2022. Otherwise, the alternative is not a return to conservative politics and policies. The alternative story about 2022 would be the gathering storm of fascistic impulses that could spell the end of the American experiment in republican governance.