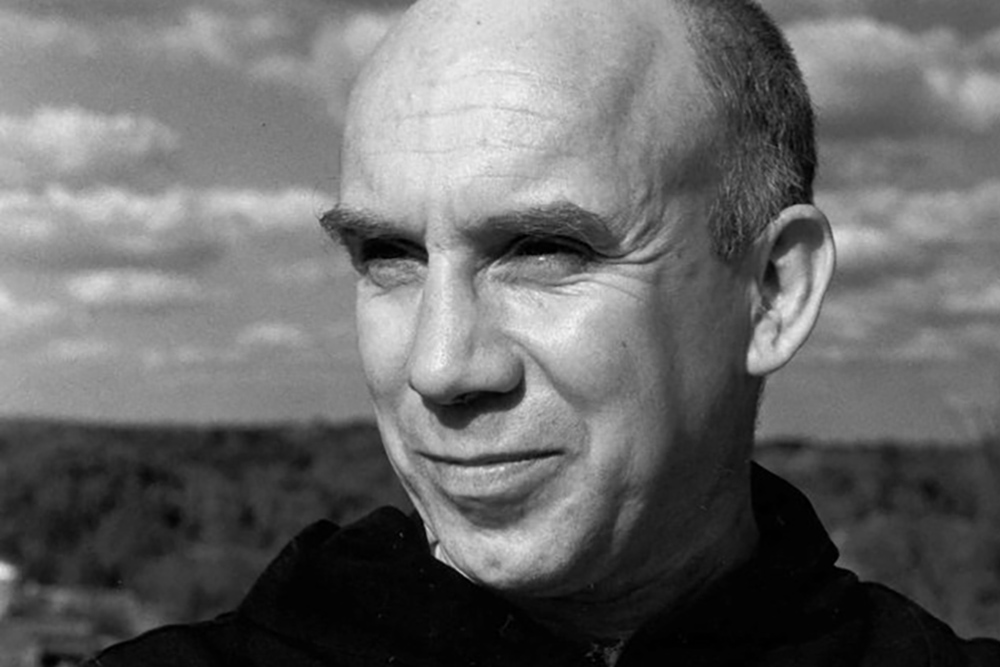

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in an undated photo (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Having read, written, taught, led retreats and lectured on the writing of Thomas Merton for many years, I am used to encountering a range of responses people have to the late Trappist monk and spiritual writer's work and wisdom.

Generally speaking, those who have actually taken the time to learn about Merton — his fidelity to his Catholic faith, his openness to dialogue with other traditions, his keen social analysis and criticism, and the broad range of topics and thinkers he engaged throughout his tragically short life (1915-68) — are usually interested and inspired by his thought and writings.

Still, some of Merton's writings can be particularly challenging and unsettling, even for those who admire him and have read his work. His writings on racial justice, war and nonviolence, and other urgent issues related to social justice can elicit a range of reactions, including resistance and defensiveness, especially when Merton's insights hit the nerves of one's conscience.

One Merton essay that always elicits a strong reaction whenever I teach it in a course or talk about it in a lecture is "A Devout Meditation in Memory of Adolf Eichmann," from Merton's 1966 essay collection Raids on the Unspeakable.

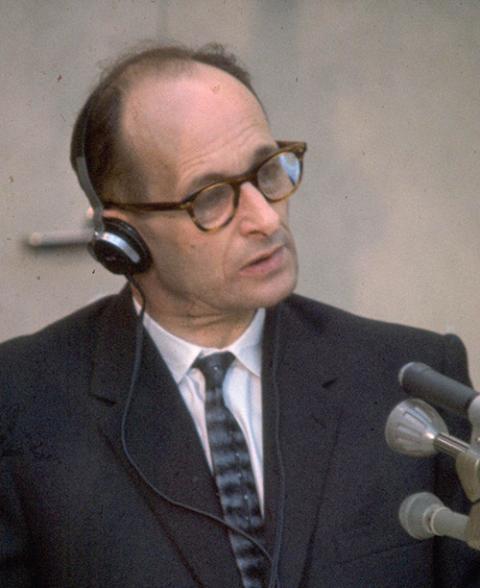

Merton's short yet powerful reflection about the 1961 trial of the notorious Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann opens with the following observation: "One of the most disturbing facts that came out in the Eichmann trial was that a psychiatrist examined him and pronounced him perfectly sane. I do not doubt it at all, and that is precisely why I find it disturbing."

Adolf Eichmann on trial in Jerusalem in 1961 (Wikimedia Commons/Israel Government Press Office/National Photo Collection of Israel)

He then reflects on what the philosopher Hannah Arendt calls the "banality of evil" in her own reporting on and analysis of the Eichmann trial in her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Merton notes that Eichmann was not the monster or "psychotic" the world imagined a Nazi mastermind to be. He was by all accounts a boring, mediocre, "unperturbed official conscientiously going about his desk work, his administrative job which happened to be the supervision of mass murder."

It is this disturbing truth that led to the harsh blowback against Arendt's book in the 1960s and it is what upsets so many readers of Merton's essay today. Merton uses the psychological diagnosis of Eichmann's sanity as a launching point for considering how so much evil — not just the unspeakable horror of the Holocaust — is daily perpetrated by "sane," "rational," "ordinary," "logical" women and men.

Merton writes: "The sanity of Eichmann is disturbing. We equate sanity with a sense of justice, with humanness, with prudence, with the capacity to love and understand other people. We rely on the sane people of the world to preserve it from barbarism, madness, destruction. And now it begins to dawn on us that it is precisely the sane ones who are the most dangerous."

Terms like "sane" and "insane" are today considered inappropriate when referring to mental illness, but classifications like "sane" and "logical" can still be helpful when thinking about how such things are determined by particular cultures. One is considered "sane" if one conforms to the expectations of the society in which one lives and works.

Merton writes: "We can no longer assume that because a man is 'sane' he is therefore in his 'right mind.' The whole concept of sanity in a society where spiritual values have lost their meaning is itself meaningless."

As if the acknowledgement that terrible evils can be perpetrated by ordinary people — bureaucrats and office workers — and not just by fantastical monsters and psychotics weren't enough for the reader, Merton makes an important move that shines the light of analysis on Christianity itself.

What business have we to equate "sanity" with "Christianity"? None at all, obviously. The worst error is to imagine that a Christian must try to be "sane" like everybody else, that we belong in our kind of society. That we must be "realistic" about it. We must develop a sane Christianity: and there have been plenty of sane Christians in the past. Torture is nothing new, is it? We ought to be able to rationalize a little brainwashing, and genocide, and find a place for nuclear war, or at least for napalm bombs, in our moral theology. Certainly some of us are doing our best along those lines already.

Is Merton saying that Christianity is insane? Well, yes. At least he is making a point similar to the one St. Paul does in opening chapter of the First Letter to the Corinthians. Namely, that Christianity does not align comfortably with "worldly" wisdom or logic (1 Corinthians 1:18-31). In fact, Paul goes to great length to explain that what Christians profess to believe is foolishness in the eyes of those who view the world through the lens of religious and societal standards of the time.

Advertisement

Merton's point, like Paul's, is not to denigrate Christianity. On the contrary, Merton is challenging self-identified Christians to evaluate their own understanding of their faith tradition, and consider how it does and does not inform their views and actions in the world. If we're being honest, most contemporary Christians see little dissonance between what it is we say we believe and how we live in the world.

As Pope Francis continually reminds us, the simplicity of the Gospel ought to challenge our complacency, comfort and conformity to the values of the "world," as Paul says.

In "The Joy of the Gospel," Francis points to Jesus' teachings and how we so often complicate and qualify them so that we remain unbothered by our faith. "This is especially the case with those biblical exhortations which summon us so forcefully to brotherly love, to humble and generous service, to justice and mercy towards the poor. Jesus taught us this way of looking at others by his words and his actions. So why cloud something so clear?"

To love our enemies, do good to those who persecute us, forgive our brothers and sisters 70 times seven, to respond to violence with nonviolence, and to love one another as ourselves are absolutely "insane" according to the standards, logic and wisdom of modern society.

Unfortunately, too often the gospel that is preached by Christians in word and deed is not that of Jesus Christ, but of power, influence, politics, control and fear.

The contrast between the "sanity" of the world and the "insanity" of Christianity Merton discusses reminds me of Duke University ethicist Stanley Hauerwas, who once wrote: "I cannot avoid the reality that American Christianity has been less than it should have been just to the extent that the church has failed to distinguish America's god from the God we worship as Christians."

Do we have the courage to risk appearing foolish, unrealistic or even insane according to the "logics" and "sanity" of big business, military powers and political agendas? Or are we content to create a god in our own "sane" image and likeness, and therefore calling the worship of such an idol "Christianity"?

Merton wrote:

Even Christians can shake off their sentimental prejudices about charity, and become sane like Eichmann. They can even cling to a certain set of Christian formulas, and fit them into a Totalist ideology. Let them talk about justice, charity, love, and the rest. These words have not stopped some sane men from acting very sanely and cleverly in the past.

Perhaps individual and collective examinations of conscience are long overdue to assess just how "sane" our Christianity actually is and whether or not we are willing to follow Jesus Christ with all the insane consequences that entails or simply continue deluding ourselves into worshiping "America's god."