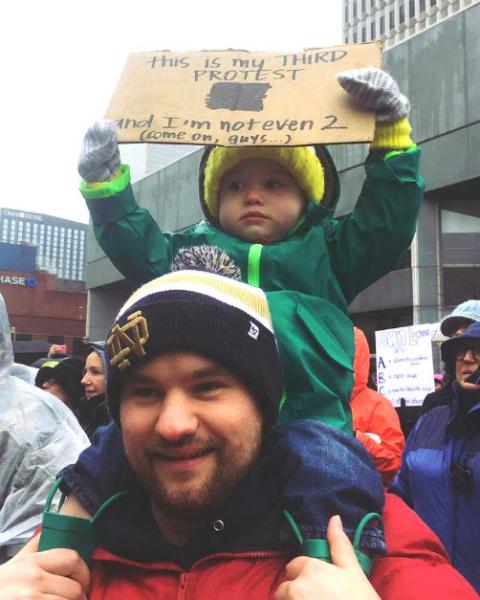

Gillian Mocek and son Simon at the Women's March in Louisville, Kentucky, Jan. 21, 2017

In our bedroom hangs a sign that my family brought to the Women's March in January 2017. It reads, "If he builds a wall, we'll raise our children to tear it down." Around the corner in our son Simon's room, another cardboard sign reads, "Arms are for hugging," from the March for Our Lives event, held after the shooting in Parkland, Florida.

And now, in the living room of our home, there is a new cardboard sign that reads, "No Person is Illegal." My wife made it before the Families Belong Together Rally held in Louisville, Kentucky, that we attended with Simon.

Our son turned 2 in May and he has already been to five protests. I guess that's the result of being born the year Donald Trump was elected president.

These signs, along with the one in our front yard that reads, "No matter where you are from, we're glad you're our neighbor," have become our symbols of resistance. It's impossible to walk around our house without garnering a clear understanding of where we stand on certain issues. There is a crucifix and a protest sign in nearly every room — we're Catholic and proud of it.

Recently, I was discussing these signs with one of my friends. We were drinking scotch on his front porch waving to neighbors and having a lively discussion like the opinionated old-souled millennials we are. We said that in our homes our sons — he has a son Simon's age — will grow up surrounded by our symbols of resistance. Or as my friend put it, symbols of our tribe — a tribe that frankly I'm honored to be part of. A tribe, defined in part by the signs around our house, of inclusivity, compassion, mercy, justice and community.

During our discussion, my friend asked, as one only can drinking scotch on the front porch, what are the responsibilities of living in our tribe? Surely, he continued, if we believe in mercy, justice and inclusivity, we can't exclude those who disagree with us, as that's fundamentally against what we believe.

Advertisement

His conclusion, therefore, was that the greatest example we can set for our children is to invite, share the table and break bread with those who believe different things, even things that are against what we believe to be right. After all, Jesus broke bread with Judas, knowing that he already had betrayed him. There are few greater examples of radical hospitality and love than that.

Henri Nouwen called the dinner table "one of the most intimate places in our lives." Not because of the table, but because of what we do at the table. "Strange as it may sound," Nouwen said, "the table is the place where we want to become food for one another. Every breakfast, lunch, or dinner can become a time of growing communion with one another."

March for Our Lives event in Louisville, Kentucky, March 24

The table is also the first lesson of faith to our children. Before they learn how to pray the Hail Mary, read the Bible, or understand what is happening at Mass, they learn about the ritual of a meal. They learn that families gather for a meal at a particular place, to be together, to pray together and to celebrate with one another.

The table is also the first place we teach our children about community. More specifically, what community means to us as parents, shown through who is invited to sit at the table.

The news the past couple of weeks has included harrowing tales of exclusion from the American table — moments where our country was willing to flirt with the inhumane in the name of protecting a seat.

As Catholics, our tribe has a symbol for togetherness and breaking bread. It's the altar, our table. And as Catholics, if we have a place in the public square, it should be as the table placed squarely in the middle. We should be the place where people can come to understand each other's humanity. This starts at our own tables. And not just the table but who we invite to sit around it.

Would Jesus invite Trump over for a steak dinner? Yes, without question. The only solution to a heart bent on exclusivity is examples of the goodness, grace and love inherent in radical inclusivity.

And, in truth, if Trump showed up on my doorstep I would invite him in. I would offer him a drink and a meal. This is what I do for anyone on my doorstep. That's what Christians should do, because that's what Jesus would do.

He would see the sign in our front yard, the crucifixes on the walls, and he wouldn't miss the "No Person is Illegal" sign as he walked in. Would it have an impact? I don't know. Regardless, it's important to speak truth to power. But it's also important to do it with love and with the hope that with togetherness brings what Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle calls kinship — an understanding that the divine lives in all of us even if it takes a while to see.

[Christian Mocek is director of alumni relations at St. Meinrad, a Benedictine monastery, seminary and school of theology in southern Indiana. You can find his reflections on parenthood, marriage and young adulthood at mocekmusings.com.]

Editor's note: We can send you a newsletter every time a Young Voices column is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page and follow directions: Newsletter sign-up.