St. Mary Parish's cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia, is seen in a 2017 file photo. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Americans don't like talking about death. It makes us uncomfortable. But experts say discussing the end of life is necessary, especially now as the coronavirus pandemic threatens to upend much of our existing dying and grieving processes.

"Now, more than ever, is the time to try to open up these kinds of conversations around fears of death and dying and what that means," said Anita Hannig, associate professor of anthropology at Brandeis University. "For many, doing that during a pandemic might be way beyond their capacity, but when is a better time?"

Hannig, who is an expert on the anthropology of death and dying, said this does not mean Americans should be apocalyptic and assume everyone will die. That's not what this is about — while the virus is more fatal for elderly people, the majority of coronavirus patients will survive. However, people might consider initiating conversations with loved ones around end-of-life wishes because "the last thing you want is to be blindsided," she said.

Multiple experts told NCR that a century of expansions in the medical and funeral industries in the United States have led to a real distancing between the living and the dying. Prior to the 20th century, people used to die in their homes and family members were heavily involved in preparing the bodies for burial.

Over time, as dying moved out of the home and out of the care of immediate family, death as a concept also moved largely out of mind for the average person. Death became taboo in American culture, labeled as "morbid," something we fear rather than discuss.

With the rise of coronavirus, Americans are now being confronted with those fears on a daily basis. Headlines enumerate death tolls and Twitter threads detail miserable battles against the virus. At a March 20 White House press conference, a reporter cited statistics showing millions of Americans are afraid. When asked what he would say to those scared Americans, President Donald Trump responded, "I say that you are a terrible reporter. That's what I say." The exchange has led to further questions about the president's ability to handle this crisis.

With limits on gatherings like funerals, the pandemic is 'really going to impact the way that we're able to find closure in the face of death, which is something that we already fear so much.'

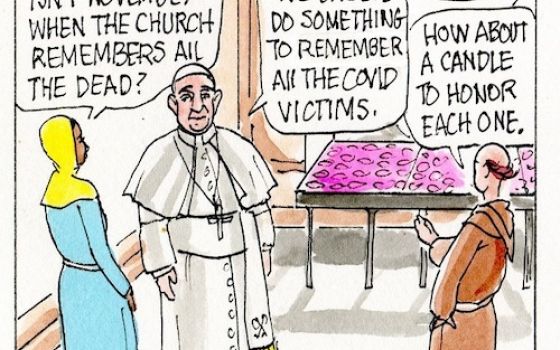

As columnist Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese writes, "A pandemic makes it impossible not to think about death."

At the same time that death is surging in collective American consciousness, preventative restrictions to stop the spread of the virus are widening the existing physical gap between the dying and their families.

In Italy — where many Americans are looking to understand what is to come — people are reportedly dying in isolation without any family or friends around. Compounding the distance, Italy has also banned funerals, replacing them with graveside services for just a few people. Immediate family members are sometimes forced to miss the services, stuck in quarantine themselves.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is recommending that funerals limit the number of mourners physically present and livestream services to family and friends at home. Catholic dioceses around the country are enacting guidelines of their own to restrict funeral sizes.

In Wisconsin, at Mary Flo Werner's funeral, only her nine grandchildren and the priest were allowed inside their Catholic church to limit the gathering to ten, The New York Times reported March 25. Outside, in their cars, her four adult children watched the service on their phones.

This amounts to what Hannig calls a "cruel irony." The pandemic is "really going to impact the way that we're able to find closure in the face of death, which is something that we already fear so much," she said.

(Pixabay/joaph)

For Catholics, the inability to be near loved ones at the end of life or gather together for funerals will be especially hard.

"We use our physical connections to the sacraments and to each other to buoy our faith," said Darleen Pryds, associate professor of Christian spirituality and history at the Franciscan School of Theology in San Diego. "Our faith is very relational."

Pryds, who is an expert on the spirituality of death, said, "Families who are not able to see one another at the end of life are often really quite traumatized by that."

Along those lines, Hannig, the anthropologist, said some historical examples — violent military coups, natural disasters, missing soldiers — show the long-term pain families can suffer when they are unable to perform traditional end-of-life rituals.

Fr. Michael Witczak, a professor of liturgical studies and sacramental theology at the Catholic University of America, told NCR via email that burying the dead is a traditional corporal work of mercy. "The funeral liturgy speaks about 'the bonds we have formed in life.' The funeral liturgy is rooted in the conviction that human beings are related and connected to one another," he said.

In the face of the current crisis, finding creative ways to sustain strong relationships will be essential to minimize potential trauma, Pryds said. Pryds herself participates in a faith-sharing group that meets through Zoom, an online videoconferencing platform.

Advertisement

"The call is really for people to reach out to the elderly through the phone and through letters, and to really encourage and talk through with the elderly the importance of social isolation," Pryds said.

"You don't have to wait until somebody is dying to have those meaningful one-on-ones," said Hannig.

If people are looking to initiate conversations about end-of-life wishes, Hannig said there are a number of helpful resources online that can help people ease into them. Those include the Conversation Project, the Order of the Good Death and Death Over Dinner.

Pryds also teaches an online course on "The Spirituality of Dying and Death" that offers people a Catholic approach to conversations about death, grounded in the Franciscan tradition. The course, which is geared toward both caregivers and people at the end of their life, offers opportunities for prayer, meditations and personal reflections.

Although culture historically has pushed us away from it, Pryds said that Christians are called to reflect on our mortality.

"That is a traditional Christian practice — to reflect on mortality," she said. "Not to be morose and not to be depressing, but in fact to turn that around and realize that each moment is precious and that life is a gift."

[Jesse Remedios is an NCR staff writer. His email address is jremedios@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter at @JCRemedios.]