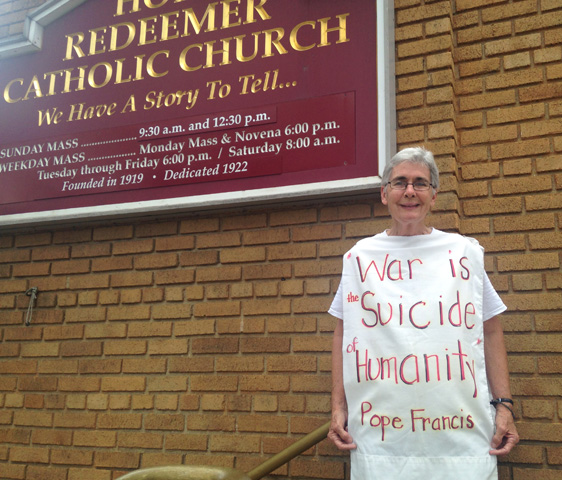

Kathy Boylan stands in front of Holy Redeemer Catholic Church in Washington, D.C. (Judy Coode)

Recalling saint reformers of the past, John Ricard, bishop emeritus of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Fla., recently praised a small group of women who, for years, have stood in silent protest during Mass each week, appealing for an end to the church's discrimination against women and complicity in war.

"I want to thank you for standing, for your witness," Ricard said. "You are a sign that the church can change. There have been others who were reformers -- Ignatius, Teresa of Avila. Thank you for believing in the church and working to change it from within."

The unexpected affirmation came at the conclusion of the 10:30 a.m. confirmation Mass held May 31 at Holy Redeemer Catholic Church in Washington, D.C. Fr. David Bava, the pastor, had just finished the final announcement when Ricard, the morning's homilist, returned to the podium to ask, "Where are the standing women?" and then proceeded to commend them.

The bishop's words of praise astonished the women, who have stood for years during Mass, unacknowledged.

"The only other time we have been affirmed from the altar was by a Jesuit priest," said Jean Sammon, a former field organizer for the Catholic social justice lobbying organization NETWORK who has been part of the standing women's protest since 1999.

"Bishop Ricard's statement was just unprecedented, a hortatory message, almost as if he were exhorting us, to say this is good," Mary Helen Washington said.

A professor of English at the University of Maryland in College Park, Washington has stood throughout every Sunday Mass for almost 20 years. The handful of women who participate in the weekly protest always stand at the back of the sanctuary or off to the side, careful not to obstruct anyone's view of the altar.

"It is a gesture to say, This is a church that does not acknowledge us," Washington said, later adding that she never "intended to stand for so many years. Now, it would be impossible to sit down. My natural position is to stand up for women in the church and in the world."

Across the aisle is Kathy Boylan, a member of the Dorothy Day Catholic Worker in Washington, D.C. Boylan stands each week to reveal various prayers for disarmament inscribed on pillowcases pinned to her shirt. Some read more like placards at an anti-war demonstration than petitions: "Soldiers put down your guns"; "War = Millions of Sandy Hook Massacres"; "No War in Russia, Venezuela, Syria."

"They are half protest, half teaching," said Boylan, who said she wants "to see the church move from just war [teaching] to the nonviolent truth of Christ."

On the morning of the confirmation Mass, she wore a quote from Pope Francis -- "War is the Suicide of Humanity."

The bishop said it was Boylan's pillowcase petition that caught his eye and that he later learned several women were protesting for gender justice. "I saw this woman standing with her message of peace and really sought to commend her," he told NCR.

The current rector of St. Joseph's Seminary in Washington, Ricard was one of the first black bishops in the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He has a long history of engagement with social justice initiatives, serving as chair of Catholic Relief Services, the conference's International Policy Committee, and its Office of International Justice and Peace.

The U.S. bishops "wrote the pastoral on peace some time ago," Ricard said. "I believe we need to be strong on this issue. Always. Certainly, the current pope leads us to support peace. We are called to be peacemakers, to work for peace, especially among ourselves, as Americans, and in the world. We live in a very polarized society."

Unequivocal in his support for strengthening the church's efforts to end war, the bishop was more muted on the subject of women. Asked if reform within the church included expanding their role, he said, "I leave it up to the current pope. He respects the dignity of all women and their contribution in the church, so I stand with him."

But Washington, who is also African-American, said the respect the church offers women is covered "with a veil of semantics, where they will say respectful things but deny you a position of leadership. If the church denied black people this kind of equality, it would be unthinkable, but it's not for women."

Holy Redeemer inherited the standing women and their two protests when St. Aloysius, a Jesuit parish located near the U.S. Capitol, merged with the church two years ago. In 1993, then-parishioner Gigi Gruenke, a clinical social worker, began standing during Mass as a simple "direct witness" on behalf of women, she said.

"Every time a woman goes to Mass, we are being discriminated against because we are women," Gruenke said. "We are not priests, not deacons, not dispensers of the sacraments. Mass at St. Aloysius used to be the better part of two hours. It was not comfortable for standing. The discomfort of standing was congruent with the discomfort of being a woman in the church."

Gradually, a few women joined Gruenke. The small but persistent group's numbers ranged from two to as many as 10 on any given Sunday. When parishioners at St. Aloysius purchased pews for the downstairs sanctuary, the protesting women bought one and inscribed it with the words: "Standing for women in church and society."

While the women's witness was accepted at St. Aloysius, Boylan's petitions for peace, which started in the mid-1990s, were not. Unlike many standard peace prayers, her appeals called for the faithful to take responsibility. Each week, during the open intercessions of prayers of the faithful, she prayed Catholics would disassociate themselves from war-making -- that soldiers would put down their guns and refuse to kill, that no young person anywhere in the world would join the military, and that everyone else would refuse to pay taxes for war.

"We can pray for an end to war, but how is that going to come about?" Boylan said.

The intercessions rankled many parishioners at St. Aloysius, some of whom had children fighting in Iraq or Afghanistan. Even peace activists within the community found Boylan's approach alienating and uncharitable. (Her critics said she once referred to taxpayers as "collaborators" and likened critics of pacifism to those who would have opposed abolition of slavery.)

At the height of the controversy, the pastor and parish council sent Boylan a letter, threatening to bar her from church premises if she continued to "violate the norms of this parish."

The threat came after lengthy meetings and extensive correspondence, copies of which Boylan has meticulously saved in a manila folder. The file is a fascinating chronicle of one parish reckoning with its response to war in the context of the Mass.

"All of creation is present during the Mass, standing with us before God," Boylan said. "We may not be able to see the billions of people, most of whom are starving, suffering in war, tortured. We don't hear their cries. Those brothers and sisters understand this prayer."

At Holy Redeemer, the deacon sings the Prayers of the Faithful. Individual petitions are recorded in a book brought up to the altar during the Mass. Not wanting to speak over the singing deacon, Boylan decided to write her peace appeals on pillowcases. "I've only been standing during Mass for a little more than a year," she said.

"I will keep standing during Mass until women have positions of equality," Washington said. "I plan to stand for a long time."

So, too, Boylan. The peace activist said she was grateful and encouraged by Ricard's remarks. "I would love to invite him for tea," she said.

But Boylan emphasized she wanted to "restore" -- rather than reform -- the church to its early expression of Christianity, when being baptized required leaving the military.

"The people of God are baptized into the life of Jesus, the Prince of Peace, and we need to go back to his example," Boylan said. "I support gender justice in the church and women in the priesthood. The truth of our baptism is that we are all priests, prophets, and rulers, and we have responsibility to live as such."

[Claire Schaeffer-Duffy is a longtime NCR contributor. She is a member of the SS Francis and Therese Catholic Worker of Worcester, Mass.]