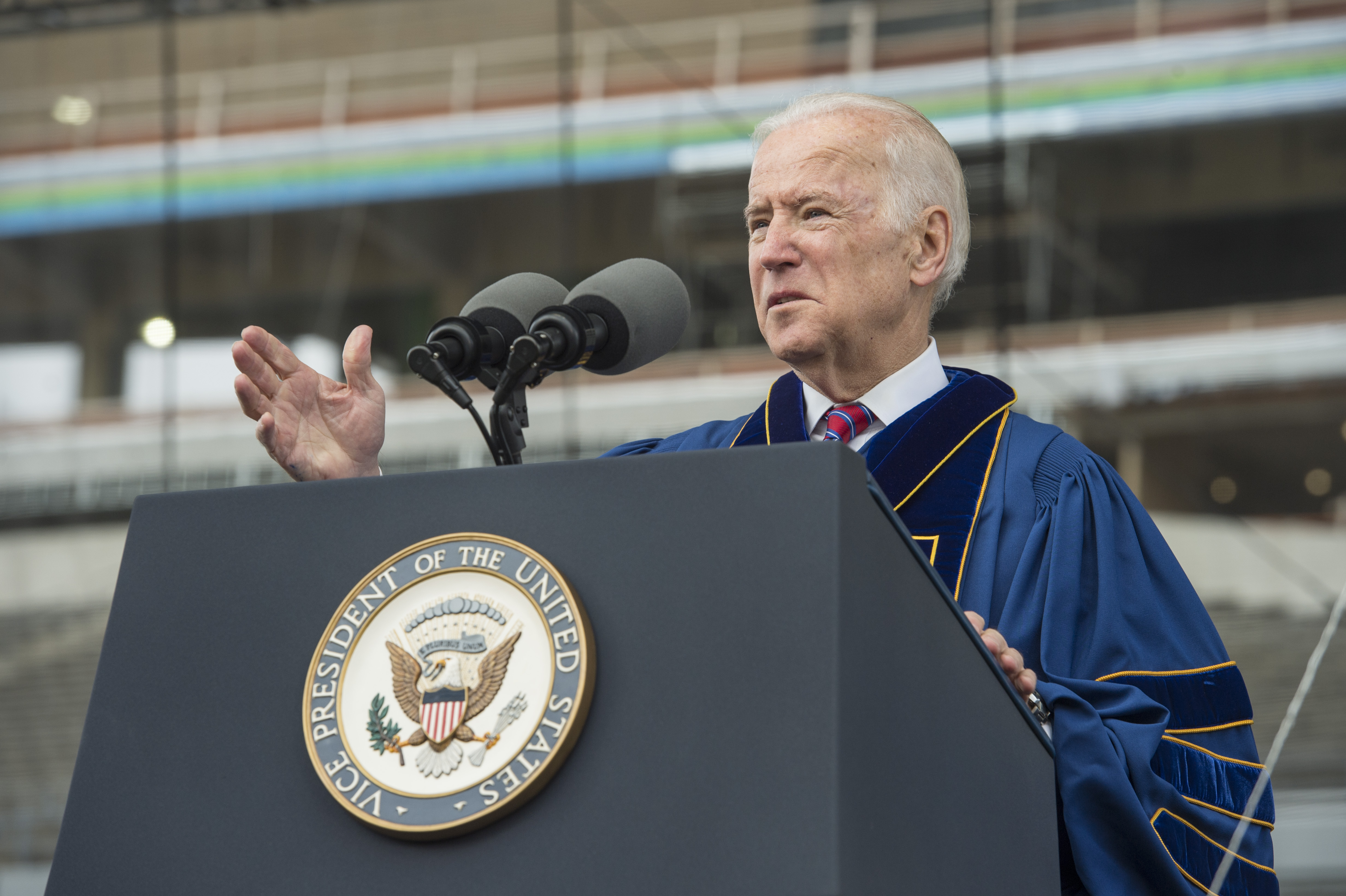

In a 2016 file photo, then U.S. Vice President Joe Biden delivers an address after receiving the Laetare Medal during a commencement ceremony May 15 at Notre Dame Stadium in Indiana. (CNS/Barbara Johnston, University of Notre Dame)

The first salvo in the 2020 campaign Communion wars was fired Oct. 27 when a pastor in Florence, South Carolina, refused the Eucharist to former Vice President Joe Biden.

The issue was Biden's stance on abortion, which Fr. Robert Morey, pastor of St. Anthony Catholic Church, described as contrary to Catholic teaching.

"Any public figure who advocates for abortion places himself or herself outside of church teaching. As a priest, it is my responsibility to minister to those souls entrusted to my care, and I must do so even in the most difficult situations," Morey wrote in a public statement after the incident.

The former vice president, considered among the frontrunners for the Democratic nomination for president in 2020, offered a muted response to the eucharistic snub.

"That's just my personal life and I am not going to get into that at all," he told MSNBC's Andrea Mitchell Oct. 29. Biden is a lifelong Catholic and reportedly attends Mass at St. Joseph on the Brandywine Church in Greenville, Delaware, part of the Wilmington Diocese.

Biden previously opposed public funding for abortion, but changed his stance after it came under attack from other rivals for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination.

In an Oct. 5 tweet, he wrote: "Roe v. Wade is the law of the land, and we must fight any and all attempts to overturn it. As president, I will codify Roe into law and ensure this choice remains between a woman and her doctor."

While Biden described the refusal of Communion as a personal issue and Morey promised to pray for the former vice president, the incident was reported extensively in the mainstream media and commented upon exhaustively in the Catholic blogosphere.

"Denying Communion to politicians, Democrat or Republican, is a bad idea. If you deny the sacrament to those who support abortion, then you must also deny it to those who support the death penalty. How about those who don't help the poor? How about 'Laudato Si'? Where does it end?" tweeted Jesuit Fr. James Martin, a popular author and commentator.

But Fr. Frank Pavone, national director of Priests for Life, said that denying Communion to politicians like Biden is justified.

"I hope more priests will follow his lead by refusing the sacrament to politicians who not only support abortion but who advocate for taxpayer funding for the murder of children," Pavone said in a press release.

Both Morey's opponents and supporters quoted canon law.

Supporters of Morey cited Canon 915 of the Code of Canon Law which states that Communion should not be given to those "who obstinately persist in manifest grave sin."

Denying Communion to Catholic politicians who support keeping abortion legal is a recurring issue, most notably in the U.S. during the 2004 presidential run of John Kerry, also a Catholic. In that year, then Archbishop Raymond Burke of St. Louis said he would deny the Eucharist to the Democratic nominee.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), then prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, wrote a memo that year which stated, "Regarding the grave sin of abortion or euthanasia, when a person's formal cooperation becomes manifest (understood, in the case of a Catholic politician, as his consistently campaigning and voting for permissive abortion and euthanasia laws), his pastor should meet with him, instructing him about the Church's teaching, informing him that he is not to present himself for Holy Communion until he brings to an end the objective situation of sin, and warning him that he will otherwise be denied the Eucharist."

But Nicholas Cafardi, a canon and civil lawyer, and former dean at Duquesne University School of Law in Pittsburgh, told NCR that the question is not so simple. And he also noted that Morey is not Biden's pastor, a prerequisite cited in Ratzinger's memo.

He quoted Pope Francis, who wrote that the Eucharist "is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak."

Those who would deny Communion to politicians like Biden have a broad interpretation of Canon 915.

"It's not manifestly clear that Vice President Biden has met the conditions," said Cafardi. By denying Biden Communion, Mosey was making a judgment that the former vice president had broken his relationship with God, he said.

Other canons argue against such a broad interpretation, said Cafardi. Canon 18 says that church sanctions should be interpreted narrowly and Canon 912 argues that baptized persons have a right to the Eucharist.

And Biden was provided no process. "Is the priest supposed to act as a judge at the moment?" asked Cafardi. And, he argued, Biden, like all under canon law, had a right to privacy in the matter, which was violated by the public nature of the act of refusing Communion.

History offered fodder for both sides.

Pope John Paul II offered Communion to European politicians known for their stance in favor of legalizing abortion. He offered Communion to then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, an Anglican at the time, who took a pro-choice stance on abortion.

While a few bishops in 2004 seemed anxious to comment on the Communion issue, this time bishops contacted by NCR shied away from the controversy. A spokesperson for the Charleston Diocese, where Mosey serves, directed questions to the pastor. Bishops in Iowa and New Hampshire, two other key primary states where Biden has been campaigning, did not respond to NCR inquiries.

But Biden's home bishop, William Francis Malooly of the Wilmington, Delaware, Diocese, is on record for allowing the Eucharist for the diocese's most famous Catholic.

In a 2008 interview in The Dialog, the diocesan newspaper, Malooly said, "I look forward to the opportunity to enter into a dialogue on a number of issues with Sen. Biden and other Catholic leaders in the Diocese of Wilmington." He said, "I do not intend to get drawn into partisan politics nor do I intend to politicize the Eucharist as a way of communicating Catholic Church teachings."

The bishop said it is "critical to keep the lines of communication open if the church is going to make her teachings understood and, please God, accepted. It is my belief that Catholics of all occupations have the same duty to examine their own consciences before determining their worthiness for the reception of communion. I think I will get a lot more mileage out of a conversation trying to change the mind and heart than I would out of a public confrontation," he added.

The Wilmington Diocese cited that 2008 statement in response to inquiries over the current situation.

Supporters of Mosey cited the historic case of Archbishop Joseph Rummel, who publicly excommunicated three prominent political figures in the Archdiocese of New Orleans for their refusal to support the racial integration of Catholic schools in 1962. That stance was largely cheered in liberal circles at the time. Rummel, a German immigrant who spent his early years as a priest in New York's Harlem, was known as a fierce advocate for civil rights. He died in 1964.

But Cafardi said that action was different. Excommunication, he noted, is a juridical process and those who are affected by it can appeal. That was not the case with Biden being denied Communion.

Advertisement

Others argued that Communion issues in this era almost always involve abortion. They point to officials such as William Barr, the attorney general, who has worked to reinstate capital punishment in federal law, contrary to Francis' recent changes in the Catholic Catechism. Barr is a Catholic.

Some argued for a ceasefire on all sides in the Communion wars.

Stephen Schneck, retired professor of political science at the Catholic University in Washington, writing for US Catholic*, noted, "While I utterly oppose Attorney General Barr for his role in the executions ordered by the Trump Administration and will lift up the church's teaching on the death penalty at every chance, I urge my fellow American Catholics on all sides in public life to forego any new rounds of the Communion Wars. Regarding the sacraments, we are wrong to judge and wrong to politicize."

Cafardi agreed, arguing that Catholics, liberal and conservative, don't want their pastors immersed in electoral politics. He counseled pastors and bishops to preach the Gospel and church teaching, not to involve themselves in partisanship.

"The Eucharist should not be used as a political weapon," he said.

[Peter Feuerherd is NCR news editor. His email address is pfeuerherd@ncronline.org.]

*This story has been updated to correct the source for Schneck's comments.