Connelly Library at La Salle University is pictured May 2016. La Salle University Art Museum is located in the basement of Olney Hall. (Wikimedia Commons/Beckwoodworth)

La Salle University, a Catholic school in a low-income north Philadelphia neighborhood with an $81.6 million endowment, has deaccessioned 46 of its museum's artworks. La Salle, named for school teachers' patron saint and the Brothers of the Christian Schools founder, hopes the Christie's sale will bring in $4.8 million to $7.3 million. But as the university downplays the decision, which supports its "new strategic five-year plan," experts say it guts its coffers and threatens to disincentivize art collectors from donating to university museums in the future.

"I was there when the appraisal was done, and we picked the works that you'd tell the fire department to save first," said Carmen Vendelin, director of New Mexico's Silver City Museum and a La Salle curator from 2006 until 2014. "They're selling off a lot of the strongest work in that collection — artistically strongest and definitely the artworks that will bring the most money in. Once you've sold it, it's gone."

Selling artwork for any reason other than strengthening collections or conserving artwork is anathema in the museum world, according to Vendelin. "It's not supposed to go to keep the lights on or to the heating bill," she said. In a joint statement, the American Alliance of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors "strongly opposed" the sale.

La Salle claims it strove to protect its collection's integrity, but Madeleine Viljoen, curator of prints at the New York Public Library and a former director and chief curator at La Salle's museum, said that's "total nonsense."

"They have basically skimmed off the very top of the collection and taken all of the big names," with the exception of Henry Ossawa Tanner's "Mary," she said. "I can't imagine what the gallery is going to look like now. They don't have enough in their vault to hang suitable substitutes."

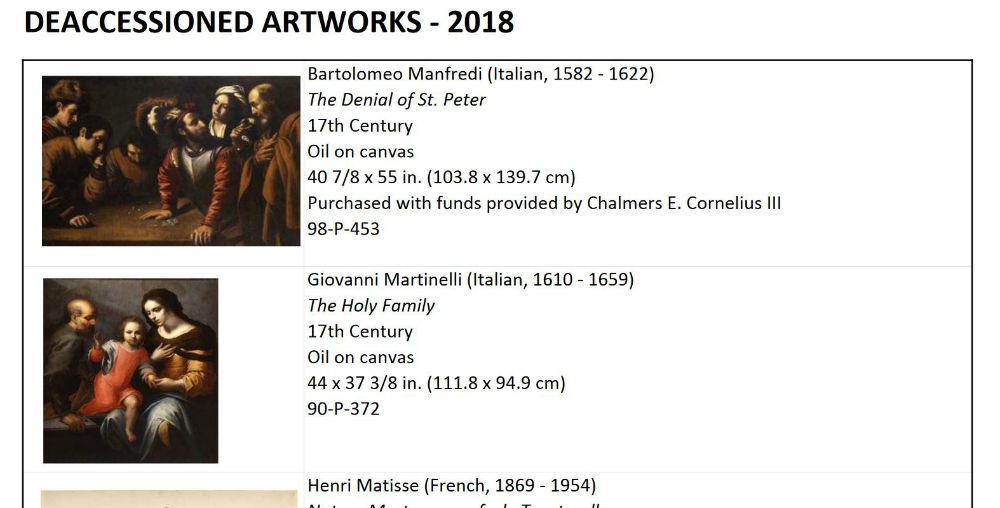

Clip from PDF of La Salle University's list of deaccessioned artworks planned for sale this spring at auction.

Among the 46 deaccessioned works are eight that the late Benjamin D. Bernstein donated, or that were purchased with funds he donated. Bernstein had a close friendship with former La Salle president Daniel Burke, who was also a Christian Brother and founder of the university's art museum, said his daughter Robin Bernstein.

"My father believed very strongly in donating to education," she said, noting that her father also donated art to Villanova University and to other schools and museums. "He felt it was important for people to be exposed to art."

Bernstein learned that her father's work was being deaccessioned via email, and then in a letter from the university. "I was more annoyed about that than that they were doing it, to tell you the truth," she said. "It is what it is. You can't control from the grave."

Although she is disappointed, Bernstein, who serves on other university boards, understands that La Salle is having financial challenges. "They've picked some good works with which to maximize their return," she said. "Does it make me happy? Of course not. My father loved Daniel Burke. I'm sure Fr. Burke would not be happy about this. But as they say, stuff happens."

Advertisement

Bernstein acknowledges that big and small museums alike can have shifting missions, or can change priorities under new leadership. But she has learned from La Salle's deaccession.

"For myself, I would be more apt to give to an art institution than a school, because of this experience," she said.

When he advises clients, Evan Beard, national art services executive at U.S. Trust, Bank of America, encourages collectors who are considering donating art to consider the mission of the institution when assessing risks.

"If you're gifting works to an institution, whose mission is broader than the arts mission, there's going to be a point in time where maybe that educational mission is going to go in a different direction than the arts," he said.

La Salle's deaccession sounds like it's filling a budget shortfall, according to Beard, who isn't dogmatic about a school deciding that hanging a Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painting on the wall isn't fulfilling its educational mission. "I don't actually fetishize over an institution selling that to someone else, who could have better use for it," he said. But it should be completely upfront and own up to art not fitting its five-year strategic plan.

"If you're gifting works to an institution, whose mission is broader than the arts mission, there's going to be a point in time where maybe that educational mission is going to go in a different direction than the arts."

— Evan Beard, national art services executive at U.S. Trust, Bank of America

"If they want to sell the most valuable works, they should think long and hard on whether they should have an arts educational mission at all that's in the form of a museum," Beard said.

Universities are risky places to donate artwork to, because the museum reports not to a museum board, but to the university's board of trustees. And that board's mission is broader than shepherding artwork, according to Beard, who foresees an evolving museum field, as many institutions have large operating budgets coupled with small endowments.

"We're entering, I think for the first time ever at least in U.S. history, a period of mergers, alliances, and in some cases potentially acquisitions in the museum space," Beard predicts.

Irrespective of the museum's long-term status, the current deaccession of the 46 works is a surprisingly unethical decision for a Catholic school in an impoverished part of Philadelphia, which was founded on the value of charity, according to Viljoen, the former La Salle museum director. "It's exactly what the university prides itself on — it's there for the poor. It's there for the needy," she said.

The museum's collection belongs to the university, Viljoen allows, but it is also part of the public trust, and gutting it not only hurts the university but also the underserved populations who visit it. "It's immoral what they are doing," she said. "It's a huge disservice."

La Salle students making a sign protesting the sale of 46 pieces from the university's art collection (Courtesy of Sarah Palma and Brittany Cohen)

And the timing of the deaccession, which came just over two years after Burke died, is also suspicious. "I think it would have put him in his grave," Viljoen said. She adds that La Salle has brought in a lot of high-paying senior managers, who crafted a strategic plan that gives short shrift to the humanities.

The current university president, Colleen Hanycz, is the school's first secular appointment. "I find it hypocritical," Viljoen said. "It doesn't seem right to be professing this ethical consciousness while doing something that I think is really heinous."

La Salle declined several opportunities to comment.

The university has drawn the ire of alumni as well. A Change.org petition has drawn nearly 1,300 signatures. "Selling the university's most valuable asset can't be the only option," it states.

Alex Palma, who holds both undergraduate and graduate degrees from La Salle, was "utterly devastated" when he heard about the deaccession. "The sale goes against everything I learned in graduate school about museum collections," he said. "I really doubt that the public will ever regain access to all 46 of these works. You can't put the genie back in the bottle."

The sale, to Palma, undermines longstanding Catholic commitments to intellectual and artistic traditions. "Nationally, I think there are a lot of institutions that are keeping an eye on this sale, because if the La Salle administration can pull it off, weathering the controversy to make a quick buck, I'm sure that you'll see more deaccessions like this from other universities and colleges popping up pretty quickly," he said.

La Salle, and any others that follow, err in their assumption that art museums are liquid assets, said Vendelin, the New Mexico museum director.

"There's this perception that museums have cash resources. That's not usually the case," she said. "The value is in the collection that's been donated, and then that's really something where you're needing to raise money and continue taking care of it."

Burke helped assemble La Salle's museum at a time when such a strong collection could be constructed. Today, art is pricier and tax deductions for donors are less generous. La Salle's collection, uniquely, showcases women modernist artists, who don't typically receive such prominent attention in museums, as well as religious works, according to Vendelin.

"In Renaissance paintings, you're going to see a lot of religion. When you get to modern, maybe that's more unusual that we had a 20th century temptation of St. Anthony and other subjects like that," she said. "I think that is important — that these topics are still relevant, and we are looking at them in new ways that have a lot to do with our contemporary context."

Viljoen would certainly think twice before donating artwork. "I can't imagine what the donors of the institution feel about this," she said.

"They did it on Jan. 2, thinking they would not get as much press, but of course everybody has come down on them like a ton of bricks," she added. "You can't get away with this. If they proceed, it will be under a dark cloud that will follow them in perpetuity."

[Menachem Wecker is the co-author of Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]