People attend Pope Francis' celebration of Mass adjacent to the airport in Tacloban, Philippines, Jan. 17, 2015. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

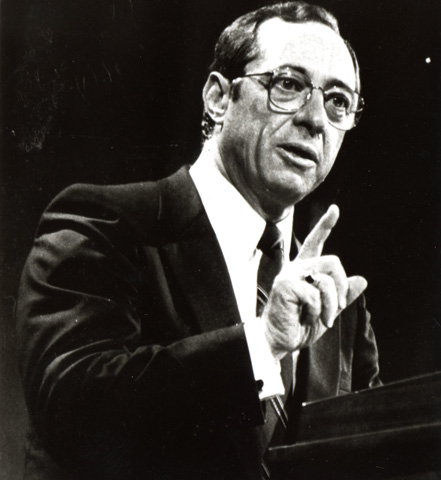

Amid the sweeping tributes for former New York Gov. Mario Cuomo following his death on Jan. 1 at 82, some of the loudest praise is coming from liberal Catholics for the brand of moral and political seriousness that Cuomo brought to public life. The reaction was understandable: Cuomo, whose son Andrew was sworn in for his second term as the state's governor the same day as his father's death, was the Democratic Party's most engaging defender of classic liberal policies and an eloquent promoter of Catholic social justice teachings.

The son of Italian immigrants who worked his way up society's ladder, the elder Cuomo repeatedly invoked his Catholic faith and his church's doctrines to advance policies ensuring that others would have the same chance, and that if they didn't, they would not be abandoned.

Cuomo was also just as famous for elaborating a rationale by which Catholic politicians like himself could be personally opposed to abortion but could still support and defend a legal right to abortion. Cuomo's nuanced position was seen as key to allowing Catholics who support abortion rights -- mainly Democrats -- to run for office without continually running afoul of the Catholic hierarchy, or alienating Catholic voters.

Yet even as these "Cuomo Catholics" grieve for the great orator who was the Democrats' greatest foil to Ronald Reagan, they may want to consider whether Cuomo's moral calculus has come back to haunt them. Now, a new generation of Catholics conservatives -- mainly Republicans -- invoke the same kind of "personally opposed" ethos to part ways with their church on issues like economic and foreign policy, the death penalty and immigration reform.

Indeed, Catholic GOP leaders and their intellectual allies have repeatedly used the principle of "prudential judgment" -- that is, using one's best ideas as to what policies would best achieve desired ends -- to argue that while they respect the bishops, prelates should not be telling politicians what to do, or how to do their job.

That was the central takeaway from Cuomo's 1984 address on religion and public life at the University of Notre Dame, a lecture that is a cornerstone of his legacy as a Catholic politician. It was, as Washington Post columnist (and proud liberal Catholic) E.J. Dionne wrote, "the liberal Catholic Speech Heard Round the World."

At the time, Cuomo was in his first term as governor and was engaged in a fierce running battle with Catholic leaders -- mainly the outspoken archbishop of New York, Cardinal John O'Connor -- over whether you could be a good Catholic and still support Roe v. Wade.

The issue was emerging with particular force as the Supreme Court's 1973 decision legalizing abortion was becoming settled law, and also a cornerstone of the Democratic agenda.

At the same time, the Catholic hierarchy was taking a decidedly more conservative turn under Pope John Paul II. Abortion was the salient issue for the U.S. bishops, a nonnegotiable point that no Catholic pol could ignore if he wanted to stay in the good graces of the bishops, or, in the view of some, be eligible to take Communion.

Rep. Geraldine Ferraro, Cuomo's fellow New Yorker and Italian Catholic, had just made history as Walter Mondale's running mate, and she also supported abortion rights. It was left to Cuomo to provide a Catholic intellectual defense against her many critics.

"While we always owe our bishops' words respectful attention and careful consideration, the question whether to engage the political system in a struggle to have it adopt certain articles of our belief as part of public morality, is not a matter of doctrine: It is a matter of prudential political judgment," Cuomo said in the landmark Notre Dame speech.

Cuomo even anticipated conservatives' adoption of his stance when he asked if he would have to follow the bishops' teaching on economic justice "even if I am an unrepentant supply sider?" And he pointedly quoted Michael Novak, known as the Catholic "theologian of capitalism," who wrote: "Religious judgment and political judgment are both needed. But they are not identical."

The speech was supposed to defend Cuomo-style Catholics and perhaps find some common ground for a truce in the emerging intra-Catholic culture wars.

But the reactions, both positive and negative, were so "explosive," as Dionne put it, that it only exacerbated the debate. Liberals saw it as the final word, while conservatives saw it as the creed of "cafeteria Catholicism," a red flag to rally more passionate opposition.

Cuomo's vision may have won out, since nearly all Catholic politicians are cafeteria Catholics now -- picking and choosing which Catholic teachings they want to highlight.

Yet at least two critical differences should not be overlooked in the post-mortems.

First, throughout the Notre Dame speech, Cuomo was clear, repeatedly and insistently, that he supported church teachings against abortion and even contraception. It's hard to envision many Catholic Democrats -- or even many Republicans -- doing either today.

Second, Cuomo was also clear that outside of a legal ban on abortion -- which he argued could be counterproductive -- he wanted to find ways to reduce abortions, a position that even Democrats who used to invoke the "safe, legal and rare" mantra now seem disinclined to deploy.

In reality, the so-called "social issues" agenda that features opposition to (or support for) issues like abortion and gay rights are not working for either party. Instead, they are giving way to arguments over economics where the roles are reversed: Conservatives argue for less government control, and liberals argue for greater state intervention.

Yet Cuomo was also a relic, in some respects, in arguing that American society could not ignore the moral aspects and ramifications of either the economy or personal behavior.

In his Notre Dame speech, he specifically cited the "seamless garment" argument of Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, then archbishop of Chicago, arguing that Catholics in public office, both conservative and liberal, are challenged to protect and foster life at all stages.

Bernardin's legacy would be eclipsed soon after Cuomo's own political career ended -- Bernardin died in 1996, two years after Cuomo left office -- yet it has actually made an unlikely comeback under Pope Francis, who is clear that Catholic teaching on economic justice, immigration and war and peace cannot be separated from Catholic doctrine on abortion, and in fact needs to be preached more vigorously.

The difference is that when the pope makes his first U.S. visit in September, he will have no obvious choir to preach to, as John Paul and Benedict XVI did. Instead, his views will face a tough sell with the faithful in both parties.

Mario Cuomo is dead, yes. But "Cuomo Catholicism" will likely long outlast him.