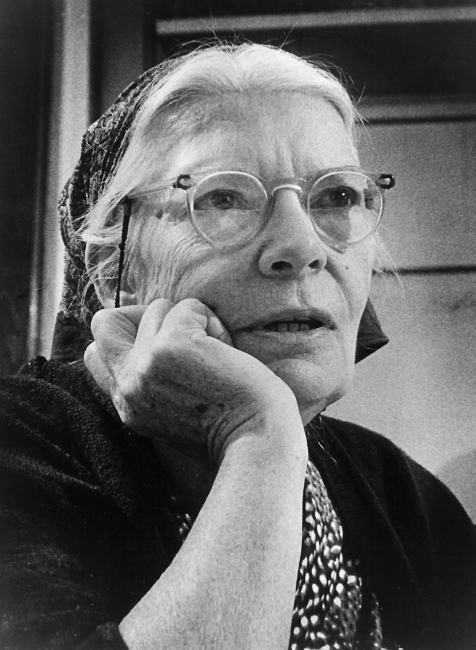

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, spent her adult life as an advocate for the poor and the rights of workers. (CNS photo/courtesy Milwaukee Journal)

I was on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol along with many thousands of others listening to Pope Francis’ address to Congress on Sept. 24, when he singled out and praised Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement. With the mention of her name, the murmured question, “Dorothy Day, who’s she?” was audible over the scattered applause and cheers of the few who know her and who share the pope’s good opinion of her. As a lifelong Catholic Worker who knew and worked with Dorothy Day in my youth, I watched with interest, amusement and some trepidation as over the next hours the worldwide media rose to the challenge of answering that question.

It was disconcerting, but no surprise that a theme picked up immediately by major media outlets was Day’s disapproval of abortion and birth control. Few reports of her neglected to mention that she “ardently opposed abortion,” was “unflinchingly anti-abortion and anti-birth control” and that she “staunchly opposed to the practice” of abortion. The New York Times went along with the trend, but with a significant nuance most lacked. Only moments after the pope’s speech, the Times cited one of Day’s associates who pointed out that “she could have, at any time, come out publicly and politically against abortion. She did not ... When she spoke of abortion, it was in terms of forgiveness, not criminality.”

I arrived at the Catholic Worker in 1975, five years before Dorothy Day’s death and seven years after the encyclical Humanae Vitae condemned artificial birth control and only two years after the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Roe v. Wade, made abortion legal. These were hot topics for the Catholic press in those days, but The Catholic Worker was an exception. I was not yet 20 years old but began writing for the paper not long after arriving, and I was an associate editor before I moved on to another Catholic Worker community in 1979. I do not remember hearing her articulate it as a policy, but there was clear understanding that Day was adamant that birth control and abortion were not among the many controversies that would be contended with in the pages of The Catholic Worker.

This reticence was a 40- year-old tradition by that time. As early as 1935, less than two years after The Catholic Worker’s founding, Day wrote to the archdiocesan censor in response to his suspicions about the editorial line of the newspaper she edited — Day assured him that while The Catholic Worker supports “all that is being done to give free, or reasonably cheap care to mothers in the way of clinics and hospitals, prenatal and post-natal care,” she also insisted that “we are not going into the subject of birth control at all as a matter of fact.”

On only a few occasions, Day lapsed in her resolve, and the unfortunate result is that she has been widely misquoted since the pope’s speech as saying, “to me, birth control and abortion are genocide.” This misconception has its origins in an open letter to Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan that she published in The Catholic Worker in 1972. Writing about Cesar Chavez and the Farm Workers' Movement, Dorothy parenthetically said “(They, together with the blacks, feel and have stated this, that birth control and abortion are genocide)” to which she added, “I agree with them.” This context is critical: Many zealous supporters of abortion rights would also agree with Cesar Chavez that birth control and abortion, when used as a method of controlling the population of the poor and promoted in the absence of healthcare and education, represents no “choice” but is truly a form of genocide.

In 1973 in an article for Commonweal magazine Day made another one of her rare comments on these issues, citing Zachariah, “We have knowledge of salvation through forgiveness of our sins” and continued, “I hope your readers can read between the lines from the above and recognize what my positions on birth control and abortion are.”

The knowledge that Day had had an abortion herself as a young woman was held in secret from most who knew her until after her death. Dorothy’s own position on abortion and birth control was held almost as privately and close to her heart as that. Far from being ardent, unflinching and staunch, as it is reported these days, her opposition to abortion and birth control was quiet and personal. Her positions on these matters were such that, in her own words, one would need to “read between the lines” to find.

Dorothy never spoke, wrote or marched in favor of criminalizing abortion. This may be because while the draconian laws forbidding abortion that were in place in 1920 did force her into a back alley, they did not save the life of her unborn child. Moreover, she believed for years that she was made sterile by the crude and unsanitary procedure she suffered, so that she regarded the later birth of her daughter Tamar as a miracle. Laws against abortion offered her no protection but only added more pain, destruction and degradation to a most wretched experience in her life.

In this same open letter where she mentioned abortion and genocide in the same parentheses, the solution Day offered was not the passing of restrictive laws but the reformation of the church. “Up and down and on both sides of the Hudson River religious orders own thousands of acres of land,” she lamented, “cultivated, landscaped, but not growing food for the hungry or founding villages for the families or schools for the children.” She well understood, she said, the biblical phrase “in peace is my bitterness most bitter.” Day confessed to Dan Berrigan her inner struggle to “reconcile this with Jesus' new commandment of non-resistance, of loving others, forgiving others seventy times seven — forgiving and loving.” The ones Day prayed for the strength to forgive were not the pro-abortionists, but “the enemies of our own household,” the comfortable churchmen she described in the harshest terms, who dared stand in judgement of poor women and their families.

Day often spoke to me of one of her favorite novels, Bread and Wine, and of her love for its author, Ignazio Silone. Set in Fascist Italy, the story’s protagonist is a Communist partisan operating clandestinely in the disguise of a Catholic priest. He cannot avoid being led to the bedside of a young woman dying from a botched abortion without blowing his cover. He cannot offer her sacramental absolution, of course, but does give her this consolation: “Have no fear; you are forgiven. What will not be forgiven is this evil society that forced you to choose between death and dishonor.”

The media’s preoccupation with reproductive issues above others is not their own invention, this time. In 2000, Cardinal John O’Connor launched the process to canonize Dorothy Day a saint along with a number of dubious details about her life and thought that have since become entrenched in the public perception of her. Some of these were aimed at promoting her as a saint “especially for women who have had or are considering abortions.” More recently, in November 2012, it was reported that when the U.S. Catholic bishops unanimously voted to support Day’s canonization, Cardinal Francis George “drew applause … as he promoted Day’s canonization by enlisting her in the bishops’ battle against the Obama administration’s contraception mandate and endorsement of gay rights.” “Dorothy Day is a good woman to have on our side,” George said.

The emphasis on questions around human reproduction that Day largely avoided in her lifetime has become a successful distraction since her death, all too often overtaking her unrelentingly ardent, unflinching and staunch condemnations of militarism and capitalism and the evils that come from them. This much is clear — Dorothy is not being enlisted into the bishops’ battle against contraception, as Cardinal George suggested. Expending his unfortunate and militaristic analogy, it is better to say that she is being drafted, conscripted posthumously and against her will into battles that are not hers.

Pope Francis, thankfully, did not invoke Dorothy Day on the side of the U.S. bishops’ culture war, and he had previously criticized such “obsessions” with abortion, gay marriage and contraception as detrimental to the other issues of justice, peace and provision for the needs of the poor. “It is not necessary to talk about these issues all the time,” Pope Francis said, a truth that Day realized more than eighty years ago.

We are in the midst of a Third World War, Pope Francis noted while visiting the Philippines last year, “spread out in small pockets everywhere.” The current world war, the pope says, is “one fought piecemeal, with crimes, massacres and destruction.” In the midst of a world war and catastrophic climate change, the world desperately needs Day’s call to a revolution of hospitality, resistance to war, simple living and nonviolent love.

[Brian Terrell lives at the Strangers & Guests Catholic Worker farm in Maloy, Iowa, and is a co-coordinator of Voices for Creative Nonviolence. Find him on Facebook.]