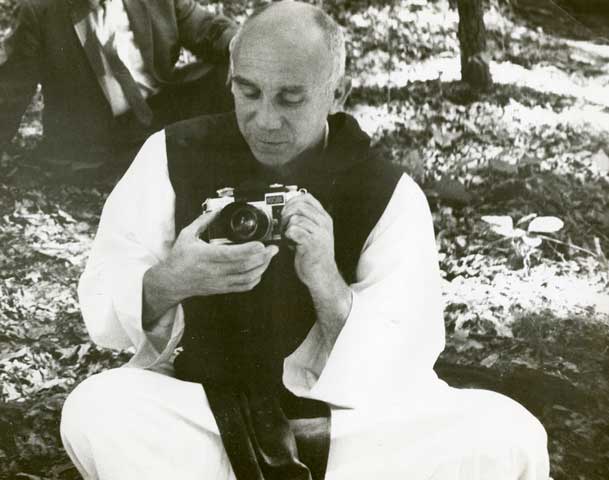

Trappist Fr.Thomas Merton in 1966 (Estate of John Howard Griffin)

In his published novel, My Argument With the Gestapo, Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton writes, "If you want to identify me, ask me not where I live, or what I like to eat, or how I comb my hair, but ask me what I am living for, in detail, and ask me what I think is keeping me from living fully for the thing I want to live for."

A good measure of Merton's identity is contained in the exhibition "Seasons of Celebration: Thomas Merton at 100," which opened Feb. 2 at Columbia University's Butler Library and runs through May 29. In a dozen glass cases, the exhibit profiles Merton the writer, interfaith dialogue partner, peace and racial justice activist, as well as the photographer, cartoonist, calligrapher and correspondent.

Though the viewer sees many photos of Merton the monk in his Trappist black-and-white habit, it is harder to fit his mysticism and contemplative yearnings into display cases. Where these are most apparent are in the monk's own photo studies of nature and landscapes.

On display is the Swiss-made Alpa 6c camera loaned to Merton by his biographer John Howard Griffin. Its case open and the camera beside it, the viewer can almost feel Merton's fingers around the device.

Griffin thought lending the camera to Merton "was like placing a concert grand piano at the disposal of a gifted musician who had never played on anything but an upright. ... The camera became in his hands, almost immediately, an instrument of contemplation."

The device, Griffin wrote, became for Merton an expression of "his vision: the challenge to capture on film something of the solitude and silence and essences that pre-occupied him."

Merton loved Columbia University, where he was a student from 1935-41. Turned loose in its library, Merton was "turned on like a pinball machine," he wrote, by the works of William Blake, St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Jacques Maritain and "the sacraments of the Catholic Church."

This turn was quite a contrast to his previous year of debauchery and drinking at Britain's Cambridge University -- which he left not in scholarly disgrace, but facing a possible paternity suit. His financial guardian in London shipped Merton off to his maternal grandparents in Long Island, N.Y. Once enrolled at Columbia, he won appointments to edit the school's yearbook and work on the university review The Columbia Jester.

Merton also made friends for life at the university. His six closest mates -- three of them Jewish, all of them writers and/or teachers -- attended his baptism in November 1938 at Corpus Christi Catholic Church in New York, and his ordination at the Abbey of Gethsemani in rural Kentucky a decade later.

Another close friend, Columbia University Professor Mark Van Doren, recognized Merton's poetic gifts when the young Englishman enrolled in his English literature course in 1935. Before departing for Gethsemani in 1941, Merton sent Van Doren typed copies of all his poems. Donated to the Columbia library by Van Doren, these poems and other manuscripts constitute a chief element of the exhibit.

So, too, do the original manuscript pages of Merton's autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, which the monk gave to Salvatorian Sr. Therese Lentfoehr, with whom he corresponded over many years. Lentfoehr organized an early Merton exhibit at Marquette University Law School in 1949, only months after his autobiography had become a best-seller, and his book on contemplative life, Seeds of Contemplation, had sold 40,000 copies in just four months.

Gazing at Merton's original manuscripts -- all of them written before computers or even Wite-Out or correction paper -- one is dumbfounded by the sheer manual labor required to type X's across words, sentences and entire paragraphs in the editing process. Imagine, if you can, Merton writing 50 books plus seven volumes of diaries all during the four hours allotted daily for work in the monastic schedule.

Columbia sparked Merton's dual vocation -- the scholar-writer and the priest. In a letter to Van Doren inviting him to his ordination, Merton confided: "I know the priesthood is going to be something tremendous. A kind of death to begin with. But that is good."

He added that once he put on his priestly vestments, "I was bowled over by the awareness that this was what I was always supposed to wear, and everything else, so far, has been something of a disguise."

The exhibit also discloses the importance of the Virgin Mary in the monk's life. In 15 years as master to scholastics and novices preparing to become Trappist priests and brothers, Merton devoted more than a third of his lecture conferences to the mother of Jesus. In a note on the Marian hymn "Salve Regina," Merton calls it more than art or choral prayer: "It is a mystical cry from the inmost depths of fallen man."

Fr. Raymond Rafferty, the retired pastor of Corpus Christi, hopes the exhibit will introduce Merton to younger people and show them the depth and width of his life. The exhibit shows the great arc of his contacts with writers, government officials, and people representing various religions, the priest said.

"I think people can learn much from him as to what we can do in this world today, and how we can treat people," Rafferty told NCR. "I believe his own inner and liturgical life opened him eventually to people, so that even from a monastic cell, he was a voice."

When Notre Dame Sr. Kathleen Deignan, a Merton scholar and professor of religious studies at Iona College in New Rochelle, N.Y., reflects on Merton, she sees someone who "keeps expanding" even as he recedes from us. "We have to catch up to do the analysis and the work he has set before us," she wrote in an introduction to the exhibit.

Merton described that work in 1967: "The contemplative has nothing to tell you except to reassure you and say that if you dare to penetrate your own silence and risk the sharing of that solitude with the lonely other who seeks God through you, then you will truly recover the light and the capacity to understand what is beyond words and beyond explanations because it is too close to be explained."

"Seasons of Celebration: Thomas Merton at 100" is open and free to the public Monday through Friday in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

[Patricia Lefevere is a longtime NCR contributor.]