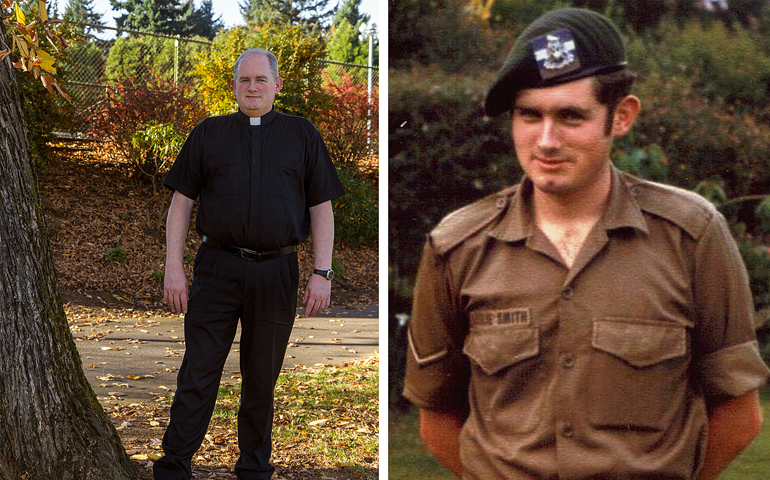

Fr. Peter Smith, vicar general and moderator of the curia for the archdiocese of Portland, Ore., is pictured in a combination photo, showing him today in late October and in his military uniform in the late 1970s. (CNS/Catholic Sentinel/Le Vu)

There's nothing like aimed shots from a zeroed-in, Soviet-made sniper rifle cracking over your head or auguring into the sand around you to clear one's mind on staying alive.

That's how Peter Smith reacted in 1976 when his South African army rifle platoon engaged insurgents in northern Namibia.

"There's nothing like the possibility of sudden death to help one focus on what's really important," said the former infantryman who, at age 18, saw the opportunities of life before him and death an infinity away. "The experience really helped my self-confidence, and it helped me grow."

Now 55, Fr. Peter Smith, vicar general of the Portland archdiocese, is the No. 2 official of the Catholic church in western Oregon. The priest, who also is moderator of the curia, said he would not wish to repeat his wartime experiences in Southern Africa but he is grateful he had them.

"God used those experiences to give me direction in my life," said the canon lawyer, who lives in community with two other priests and a religious brother in north Portland. He is a member of the Brotherhood of the People of Praise.

"When God intervened in my life, I was able to see it," he told the Catholic Sentinel, Portland's archdiocesan newspaper.

He spent almost six months in the bush along Namibia's northern border with Angola, where Soviet- and Cuban-backed insurgents of the Namibian independence-seeking South West Africa People's Organization operated out of sanctuaries in Angola provided by the leftist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola.

His unit operated in the flat savannah, bush-covered desert, setting up ambushes or overturning ambushes sprung on them in so-called "shoot and scoot" small unit skirmishes. The weather stayed in the 100-degree zone many days and was either hot, dry and dusty or hot, wet and muddy, depending on the seasonal monsoons.

The South African troops were better trained than the opposition, but mines and booby traps took a toll on the troops.

"We did a lot with little in the way of resources," Smith said. His majority conscript unit was led by regular South African army officers and noncommissioned officers and included African Namibian troops and bushmen trackers.

The men in his unit had to work together to survive on patrol, though they came from all strata of South African society. The Afrikaans-speakers generally supported everything about the apartheid government, while the English-speakers generally opposed the regime's racist policies, said the priest.

The brutal reality of combat occurred quickly for the priest when two of his friends were killed and several others wounded. One of those killed in action was a mate who joined young Smith at Mass on Sundays when the unit was back at base camp. The two usually read the first and second readings at Mass.

"That brings home the war to you," Smith said.

When he was discharged, he enrolled in college at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa.

The oldest of six children in a middle-class family, he grew up in the city of Pietermaritzburg, an agricultural and manufacturing city of about half a million inland from Durban, the country's largest seaport on the Indian Ocean. His father was an attorney and his mother, an archivist. He could have attended college directly after high school but chose instead to get his compulsory military service finished first.

"I am better for doing it," he said. "I am glad I did. Because military service helped me grow up and deal with the realities of life and what is really important in life."

Smith completed college with a degree in law and business and decided to leave South Africa for the U.S. and joined the People of Praise. Since he arrived in western Oregon and finished studies at Mount Angel Seminary, he has served at several parishes and now works at the Archdiocesan Pastoral Center and helps out at various parishes on weekends.

He said he misses the parish schools where he could visit at times when he needed a pick-me-up from the pressures of parish work.

"The young children are a great blessing," he said. "They have no cares in the world and often joyful enthusiasm."

As the U.S. observance of Veterans Day, Nov. 11, approached, Smith looked back on his military service and its challenges as an experience he appreciates.

"That time also helped me grow in faith," he said. "I carried a rosary my father had given me at age 10 through it all and I still have it today. It is a reminder of God's protection, blessing and direction for me."

In particular, his wartime experiences help him connect to veterans today who were in war or military service. Their experiences are common to all.

He remembers to thank his mail carrier for his service. The postman wears an American Legion poppy on his uniform, symbolizing the poppy field-covered graveyard in Flanders, Belgium, a World War I battlefield. Veterans Day was originally Armistice Day, the anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I in 1918.

"In Flanders Field" by John McCrae is a one of the most-quoted poems written during World War I. Its references to red poppies grown over the graves led to poppies becoming a memorial symbol for the dead. "In Flanders fields," it begins, "the poppies blow between the crosses, row on row."

[Robert Pfohman is editor of the Catholic Sentinel, newspaper of the archdiocese of Portland, Ore.]