A statue of Jesus facing the Golden Dome with its statue of Mary atop the administration building of the University of Notre Dame is seen Aug. 6 in Notre Dame, Indiana. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

Prominent Catholic philanthropist Timothy Busch, co-founder of the Napa Institute — a network that brings together wealthy donors, conservative Catholic bishops and Republican politicians — once boasted that he helped make the Catholic University of America "great again" with a $15 million donation. The university's business school, named after Busch and his wife, has emerged as a high-profile center in the nation's capital, known for its libertarian-inflected economics and pricey conferences that feature wines from Busch's vineyard and talks from powerful political donors like Charles Koch.

Now Busch and the Napa Institute's latest foray into Catholic higher education — funding a new lecture series at the University of Notre Dame that hosted Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as its first speaker — is sparking a backlash from professors at the university, according to interviews with faculty over the past two months. After this publication reported in August that the university's Center for Citizenship & Constitutional Government would launch a new Napa Institute Forum funded by Napa and the Charles Koch Foundation, among other sources, more than two dozen faculty signed an internal letter raising concerns and two professors ended their affiliation with a prominent institute at the university, NCR has learned.

In an October letter to the faculty committee of the university's Kellogg Institute for International Studies, professors wrote that the institute's co-sponsorship and partnerships with Napa and Koch-funded entities on campus contradict the institute's core values of democracy, inclusion and human dignity, and could compromise Kellogg's reputation with international research partners. NCR obtained the letter from a Notre Dame professor who requested anonymity.

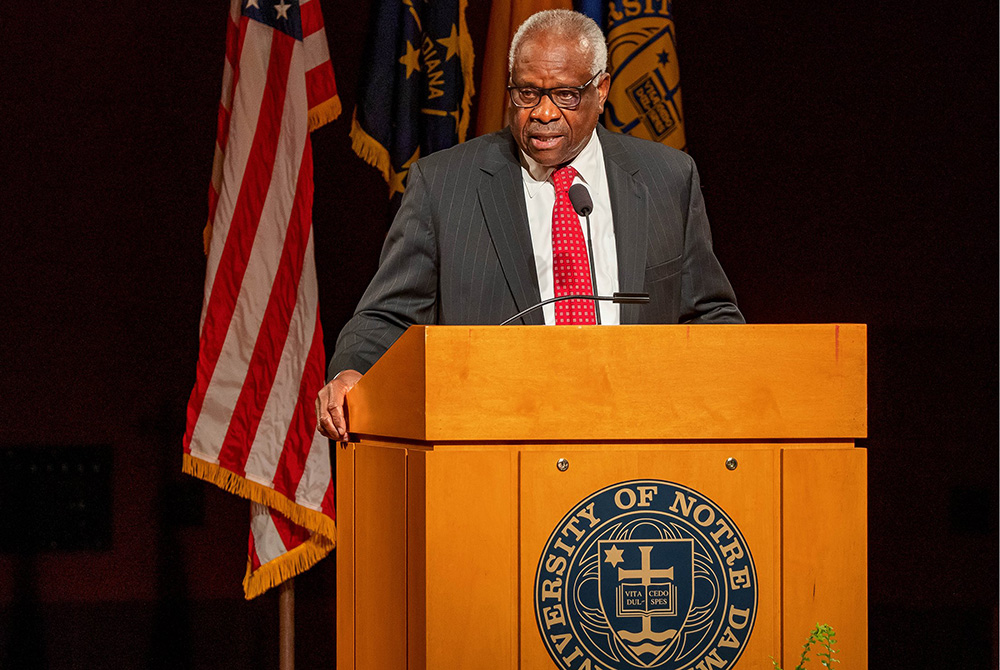

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas delivers the 2021 Tocqueville Lecture Sept. 16 at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. "We are all aware of those who assert that America is a racist and irredeemable nation," he said. "But there are many more of us, I think, who feel that America is not so broken as it is adrift at sea." Thomas also said the court doesn't make decisions based on politics or public opinion and warned against "destroying our institutions" when "they don't give us what we want when we want it." (CNS/Courtesy of University of Notre Dame/Peter Ringenberg)

Faculty began questioning the optics of taking money from Napa after the institute's summer conference, where Timothy Busch denounced the Black Lives Matter movement for "promoting racism, critical race theory, and destroying the nuclear family." This "neo-Marxist movement," Busch said, "operating under some discriminatory theory of Black Lives Matter, is attacking the American experiment, which is based on Judeo-Christian principles. We need to pray it will end or our country will be destroyed."

Another Napa conference speaker, the veteran Republican political activist L. Brent Bozell III, described President Biden as "the president of the most radical leftist ideology in history" and signed a letter that called Donald Trump "the lawful winner of the presidential election."

Disgruntled faculty have also noted that one of Napa's signature donors is Leonard Leo, the influential Washington insider who was a key architect behind Donald Trump's Supreme Court nominations. The co-chairman and former executive vice president of the Federalist Society is reportedly now working with a network of dark money organizations that, according to investigative reporter Jane Mayer of The New Yorker, are involved in multifaceted campaigns to oppose mail-in ballots and other reforms that have made it easier for people to vote, while Republican-led state legislatures are rolling back voting rights in ways that disproportionately impact voters of color.

"We should not accept money from organizations that undermine democracy or promote science denialism," said John Duffy, an English professor who has taught at the university for more than two decades. "Notre Dame is a rich, diverse place and there are a lot of competing intellectual interests here. While I disagree with many of Justice Clarence Thomas' decisions, I have no problem with inviting him here to speak. That is what a university is supposed to be about. We argue diverse viewpoints. My concern is taking money from organizations that are doing dangerous things."

Duffy also cited Koch's well-documented history of bankrolling groups that oppose efforts to address climate change. At a $2,500-a-ticket conference at Catholic University in Washington in 2017 that featured Charles Koch, the Napa Institute's Busch said Koch "shares our values" and joked: "I tell Charles he's a Catholic, he just doesn't know it."

Said Duffy: "When we take money from those organizations, we're providing cover and legitimacy to those causes and we're saying those values align with our values."

In October, the professor presented his concerns about the center's funding in an address to the university's Arts and Letters College Council, an advisory body to the dean of the College of Arts and Letters that reviews policies, practices and procedures. Duffy warned that the university would be perceived to be, in his words, "throwing in our lot with the conspiracy theorists, the race baiters and the climate deniers," if it took funding from Napa and Koch.

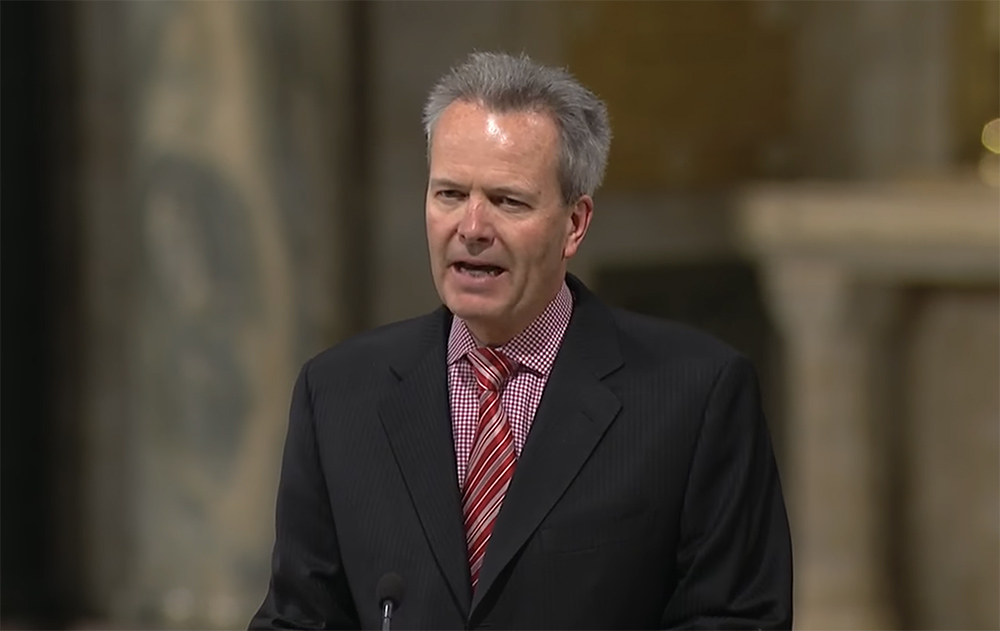

Timothy Busch speaks at the opening Mass for a Napa Institute symposium in March 2017 at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. (NCR screenshot/YouTube/National Shrine)

Dennis Brown, a university spokesperson, said Notre Dame has clear policies to vet potential contributions from donors.

"A gift must be consonant with Notre Dame's mission," Brown told NCR in an email. "We have turned down many gifts that did not meet this criterion. If the purpose of a gift has the potential to compromise Notre Dame's integrity, we will not accept it."

According to university guidelines, Brown said, "benefactors may not use the gift as a means to propagate a political or other ideological agenda." The university's specific agreements with donors are private, he said.

Vincent Phillip Muñoz, an associate professor of political science and the founding director of the university's Center for Citizenship & Constitutional Government, did not respond to several requests for comment. The Napa Institute and the Charles Koch Foundation also did not respond to requests for comments.

Muñoz announced the Napa Institute Forum lecture series at Napa's summer conference in July, highlighting Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as the first speaker.

"I couldn't be more proud to be bringing Justice Thomas back to Notre Dame, and I can't be any more thankful to Tim and Steph Busch and the Napa Institute for allowing us to make that happen," Muñoz said in a video address to the conference focused on religious liberty issues and the Supreme Court.

The new center at Notre Dame, which launched in May, "plans to expand its focus on political leadership by bringing more national political figures to campus and hosting regular events in Washington, D.C., especially with established and aspiring Catholic politicians," according to a university news release.

Notre Dame's department of political science website touts that under Muñoz's leadership the center has "raised over $16,500,00 in grants, gifts, and pledges." Francis Maier, a longtime adviser to former Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput and a member of the Napa Institute's board of directors, has been named as a research scholar at Muñoz's center.

"Those of us who object to accepting Napa funding have to be careful that we're not perceived as limiting free speech on campus," said Clark Power, a professor of psychology and education in the Liberal Studies program. "I want to see controversial issues debated and discussed, particularly in Catholic institutions. We don't want to come across as liberals trying to shut down conservatives."

But, he added, "upholding free speech does not mean that we should accept funding from Napa or other organizations whose agenda and values appear to contradict the basic tenets of Catholic social teaching. When we begin co-branding with Napa, we lend legitimacy to the Napa organization and to the political positions it sanctions. We also allow Napa and other such organizations to color how others perceive Notre Dame. This deeply concerns me."

The Golden Dome with its statue of Mary is seen Aug. 6, atop the administration building of the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana. (CNS/Chaz Muth)

A flurry of high-profile conservatives

In addition to tensions over Napa and Koch funding, some professors also cited the flurry of recent high-profile conservatives invited to speak at Notre Dame as an example of how faculty who are well connected to Republican leaders and conservative money sources can influence what issues get prioritized on campus.

Attorney General William Barr speaks in the McCartan Courtroom Oct. 11, 2019, at the University of Notre Dame's Law School in Indiana. (CNS/University of Notre Dame/Matt Cashore)

William Barr, U.S. attorney general in the Trump administration, addressed the law school on religious liberty issues in 2019, a talk co-sponsored by the university's de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture. The center's director, O. Carter Snead, is a past board member of the Napa Institute.

Justice Thomas' September speech at Notre Dame was a rare public appearance for a justice who has largely shunned the public spotlight. During his time on campus, Thomas also co-taught a one-credit undergraduate course with Muñoz, according to the South Bend Tribune.

Only two weeks after Thomas' lecture, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito gave an address at the university entitled, "The Emergency Docket," just a month after the divided court denied an emergency appeal filed by abortion providers to block a Texas law that effectively bans abortion in the state. According to the university's website, Alito's lecture was presented by the Kellogg Institute for International Studies and the institute's Lab on Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law, and co-sponsored by the Notre Dame Law School.

Catherine Bolten, an associate professor of anthropology and peace studies at Notre Dame, resigned as a faculty fellow with the Kellogg Institute after Alito's address, which was announced only a few days before he came. Bolten resigned, she told NCR in an interview, because "the institute's name and labor were being used to promote perspectives that were anathema to the institute's founding." (Bolten still remains an associate professor at the university.)

"Dignity and development is the focus of the institute, and there was nothing further away from that mission than having a Supreme Court justice speak about the shadow docket," Bolten said. "We lose sight of the important work Notre Dame is doing on the preferential option for the poor around the world when we invite any Supreme Court justice now given that the Court itself is facing a crisis of legitimacy."

Bolten added that faculty unrest over Napa and Koch funding — along with the recent attention on conservative speakers from the court — makes her fear that "the loudest voices are heard even though they are not representative of the majority in the Notre Dame community."

Tamara Kay, a professor of global affairs and sociology at the university, also resigned her faculty fellow affiliation with the Kellogg Institute as a way to highlight her broader concerns over racial equity and representation on campus.

"I wanted to start a dialogue," Kay said. "For me, it's not only about where the money is coming from, but I'm worried about maintaining the reputation of Notre Dame as a university that values diversity, inclusion and justice. The majority of people here are not racists or bigots, but for me it was important to acknowledge the fact that there is a contingent of people who are quietly, and sometimes less quietly, making inroads by putting together these programs and conferences and perspectives that actively cause harm to human beings, including Black, Indigenous, people of color, women and LGBTQ people."

Kay is helping to lead a new coalition made up of faculty, staff, graduate and undergraduate students who are strategizing about how to address issues involving speakers and events moving forward. "We support academic freedom, but we do want to be prepared when it comes to funding questions, and respond and counter speakers and events that support and spread bigotry. If Justice Kavanaugh comes, that's fine. But we will organize a teach-in on sexual harassment and an expert panel on labor rights."

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito speaks at the University of Notre Dame Sept. 30, about "The Emergency Docket," which allows the court to issue expedited rulings outside its typical process of hearing arguments and issuing lengthy opinions. It's often referred to as the "shadow docket," a term Alito called misleading, saying it "has been used to portray the court as having been captured by a dangerous cabal that resorts to sneaky and improper methods to get its ways." (CNS/Courtesy of University of Notre Dame/Matt Cashore)

The impact of major donors

The October letter to Kellogg's faculty committee also noted that unlike visits from the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor in past years, which were announced well in advance and widely advertised on campus, Alito's talk appeared to be kept closely guarded until a few days before his address. It also raised red flags about accepting Koch foundation money given what the faculty described as the Koch networks' history of funding climate change denialism.

In response to the letter, Kellogg director Paolo Carozza met with Kellogg Institute faculty fellows on Dec. 2. The meeting, which included about 50 people on Zoom and in person, was civil but also at times became tense, according to a professor who participated but who asked to remain anonymous.

In an email to NCR, Carozza defended his invitation to Alito, saying it aligned with the goals of the Kellogg Institute's Lab on Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law, which he said seeks to engage judges from "a wide variety of different constitutional and international systems, and different ideological perspectives."

"The fact that we began with Justice Alito is due to the simple fact that I have had an academic relationship with him in the field of comparative constitutional law for more than a decade," Carozza said. "I would very much like to bring other U.S. Supreme Court justices to our events as well in the future."

Carozza said neither he nor the Kellogg Institute have any relationship with the Napa Institute, but he acknowledged that faculty who have objected to Napa and Koch funding have sincere concerns since "every university has to draw some principled lines about the sources of its funding."

But, he added, "in actual practice it's an extremely difficult judgment to make in a balanced way. To focus on Koch and Napa and not, say, foundations that fund abortion advocacy or individual benefactors who have made and used their fortunes in any number of other ways that might be deeply objectionable to some members of the university community, is certainly approaching that complex moral question from one very specific and narrow ideological perspective alone."

Dianne Pinderhughes, a professor in the departments of Africana Studies and political science, agrees that funding questions are rarely simple. But she also noted that major donors can have an outsized influence at a university and impact "the hiring of certain kinds of professors, and the establishment of institutes and centers in ways that someone who is donating a thousand dollars doesn't have."

"If you have a lot of money that can make a tremendous difference in shaping the ideological agenda," she said. "The structural inequality in society then gets reproduced in the university as well."

News of the Napa Institute funding, Pinderhughes said, "was alarming and certainly prompted a lot of attention and concern among faculty."

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas delivers the 2021 Tocqueville Lecture Sept. 16 at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. (CNS/Courtesy of University of Notre Dame/Peter Ringenberg)

Those debates were heightened even more after Thomas' and Alito's back-to-back appearances at the university. "We've had visits by Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, but they didn't come within weeks of each other," Pinderhughes observed. "There are faculty who are pushing back at parts of the university that have been willing to co-sponsor these events, and there are people who feel the lectures were part of an unusual pattern. And that needs to be addressed in a very direct way."

Faculty disagreements over when funding from a donor should be considered incompatible with the university's values or in conflict with Catholic social teaching raise "sensitive and complicated" questions, said Scott Appleby, dean of Notre Dame's Keough School of Global Affairs. He described professors and deans as "regularly engaged in sometimes intense conversation and debate" over where lines should be drawn when it comes to soliciting or accepting money from individual donors and foundations.

"The views of our faculty at Keough range across the spectrum," Appleby said. "Some would prohibit our faculty or units from soliciting or receiving funds from any foundation or institution that actively supports causes inimical to integral human development, including fossil-fuel driven climate change deniers. Others would keep the restrictions only to the content of the grant itself — say, if the grant itself called for research to debunk climate change science," he said. "On the other side of the debate are those who resist any general rule governing all cases, arguing that 'orthodoxy tests' can be quite subjective."

But Appleby said there is agreement on some general principles at the Keough School, which he said "have been clarified by the debates over the Napa Institute controversy."

If the school is deciding whether to seek grants from what he called "potentially controversial sources," the deans and directors at Keough "should be transparent and broadly consultative with the faculty before doing so."

There is also consensus, he said, that "academic freedom is inviolable, with the exception of hate speech." Appleby also noted that the Keogh School's commitment to integral human development — which includes a preferential option for the poor and stewardship of the environment — must recognize that its "specific application is always open to civil discussion and debate."

A history of right-wing money

Controversy over donors is not unique to the University of Notre Dame. For years, the Koch foundations' major gifts to colleges and universities across the country have faced backlash from professors, students and advocates. After pressure from student activists and faculty led to the release of donor disclosures that revealed the Charles Koch Foundation had a say in the hiring of some professors at George Mason University, Virginia's largest public research university, the school tightened its rules governing donor agreements in 2019.

At Creighton, a Catholic university in Omaha, Nebraska, the school's Institute for Economic Inquiry, a center that has received Koch foundation funding, has faced criticism for favoring "a brand of economics that contradicts long-established Catholic social thought," according to the Omaha World-Herald.

At the University of North Carolina, Walter Hussman Jr., a $25 million donor whose name is on its journalism school, sent a flurry of emails to university officials criticizing the hiring of award-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in the weeks before her application for tenure was halted. Hannah-Jones, who won a Pulitzer Prize for leading the 1619 Project for the New York Times Magazine, was later granted tenure by the university but after the public controversy left for Howard University in Washington.

And at Yale University, Beverly Gage, a professor who has led one of the university's most prestigious programs, resigned at the end of September after she claimed the university failed to insulate the program in the face of pressure from conservative donors, including a former U.S. Treasury secretary under Ronald Reagan and a leading Republican donor who made a $250 million gift, the largest in the school's history.

Advertisement

Nancy MacLean, a professor of history and public policy at Duke University, has chronicled the more than 60-year-old effort by conservative donors to mainstream libertarian ideologies and anti-government philosophies in her book, Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America.

Centers and institutes at universities that are backed by ideologically driven donors, MacLean said, provide beachheads for cultivating research, speakers, faculty and developing a pipeline of students who will go on to other conservative networks.

"These centers at universities often have innocuous sounding names, but they are really part of an integrated strategy on the right that is connected with think tanks and conservative state policy networks," MacLean said. The Koch foundation has been particularly successful at making inroads at universities and law schools by funding niche centers, she said, including at Catholic universities where the church's social teaching clashes with libertarian, market-oriented ideologies.

"It gives these donors and causes tremendous legitimacy when they can invest in Catholic and other faith-based institutions that have a long history of social justice activism," she said. Compared to liberal donors who are often characterized by what MacLean described as driven by "causes that are often siloed," the right has "a more integrated strategy."

At the University of Notre Dame, tense debates over funding, academic freedom and what alliances with donors put Catholic values at risk won't be resolved easily.

"We have every kind of Catholic here," said Ann Mische, an associate professor of sociology and peace studies at the university. "We have progressive Catholics, liberation theology Catholics, moderate Catholics and conservative Catholics. This intra-Catholic dialogue is one of the things I love about Notre Dame."

But Mische worries that taking Napa funding after what she calls "gross mischaracterizations of the Black Lives Matter movement" crosses a line.

"The Black Lives Matter protests were attacked and belittled at Napa's convention as racist, violent and hate-filled," Mische said. "Rigorous social science research has found that the protests are overwhelmingly nonviolent and multiracial. They defend the rights of people of color in our country for protection against police brutality and other forms of inequality and exclusion. These attacks go against our core values at Notre Dame as a research institution that pursues the truth, as well as our moral commitment to human dignity and flourishing."