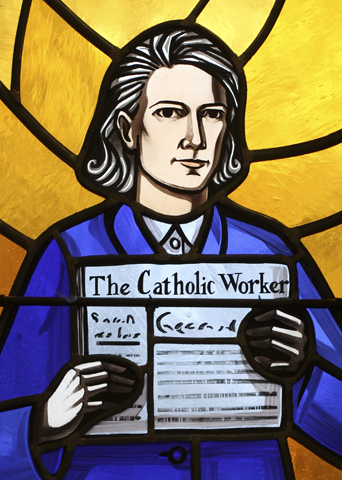

Dorothy Day is depicted in a stained-glass window at Our Lady Help of Christians Church in the Staten Island borough of New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Is it time for St. Dorothy Day? The Brooklyn, N.Y.-born co-founder of both the Catholic Worker movement and the Catholic Worker newspaper in 1933 has a gathering of both the voiceful and voiceless calling for her to be canonized.

An early tailwind wafted in when Cardinal John O'Connor of New York announced in St. Patrick's Cathedral in 1997 that it might be time to begin the bureaucratic process to get a halo atop Day, who died in Lower Manhattan in 1980. O'Connor followed through by petitioning the Vatican's Congregation for the Causes of Saints. In 2012, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops unanimously endorsed the idea. Adding heft, an advocacy group, the Dorothy Day Guild, has been formed.

On the advisory board is Robert Ellsberg, editor-in-chief of Orbis Books, the publishing house of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers. I'm hard-pressed to think of anyone whom I admire more for believing personally in the Word while professionally using full energy to get truthful and needed words into print. In 1975, at 19, Ellsberg dropped out of college to join the Catholic Worker community in New York. His five years of service were fully appreciated by Day, who made him managing editor of her newspaper.

The current issue of the Catholic Worker, selling for a penny a copy and 25 cents a year as it has since the first press run, carries a literate Ellsberg essay that argues the case for saintliness: "Ultimately the question of Dorothy's canonization is not about drawing greater attention to her, but whether, through her witness, more attention will be drawn to Jesus, and more people will be inspired to comprehend and joyfully embrace his message of radical love. I believe the answer is yes. That is why I support her canonization."

Eloquent, yes. Convincing, no. The American hierarchy's endorsement is little more than a self-serving gesture. Now that Dorothy is safely in heaven, gone for good from the picket lines, let the hosannas commence -- as assuredly her calls for pacifism and anarchism were never embraced by the church establishment, much less preached from pulpits.

And why wouldn't Catholic bishops keep their distance from the rebellious agitator? In a published 1970 interview in Kansas City, Mo., by the editors of NCR, Day spoke of "the corruption in the institutional church through money and through their acceptance of this lousy, rotten system."

What's afoot with Dorothy Day is hardly new. She is being defanged by selectively hailing her decades of running soup kitchens for the homeless while ignoring her persistent damnings of American militarism and the hierarchy's complicity. The protocol equals the sanitizing of Martin Luther King Jr., sung as the "I have a dream" man, but unsung as the condemner of the United States for having the world's most violent government.

I met Day several times, the first in 1962, when she spoke to the priests and brothers in the chapter room of the Trappist monastery in Conyers, Ga. I spent part of an afternoon with her a few years later at the Catholic Worker farm in Tivoli, N.Y.

She was a font of stories, much less about herself than about those she served. She was the soul of the American left, credible because everything she wrote in her books and newspaper columns was backed up and buffed by her daily works of mercy and rescue.

I went to her funeral on Dec. 2, 1980. Six of her grandchildren carried the pine coffin from Maryhouse on East Third Street to Nativity Catholic Church on the edge of the Bowery. In the street procession were longtime friends like Caesar Chavez and Michael Harrington, mingled among the tattered, tired and "least of these" -- the victims of the nation's economic violence.

Tellingly, no Catholic bishop was at the requiem Mass. An empurpled Cardinal Terence Cooke did show up, to sprinkle holy water on the coffin as it entered the church door. Then, his driver waiting, he hastened off.

On the canonization issue, I'm with Maggie Hennessy who, in line with Dorothy's well-known wish, "Don't call me a saint," was quoted in Kenneth Woodward's 1990 book, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn't, and Why. In reply to a group supporting sanctification, Hennessy said, "I am one of Dorothy's granddaughters and I wanted to let you know how sick your canonization movement is. You have completely missed her beliefs and what she lived for if you are trying to stick her on a pedestal. ... Take all your monies and energies that are being put into her canonization and give it to the poor. That is how you would show your love and respect to her."

Amen.

[Colman McCarthy directs the Center for Teaching Peace. His new book is Teaching Peace: Students Exchange Letters With Their Teacher.]