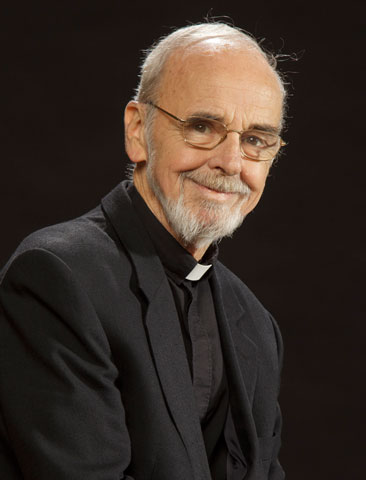

Jesuit Fr. John F. Kavanaugh (James Visser Photography)

On Nov. 5, we lost a prophet in St. Louis. Jesuit Fr. John F. Kavanaugh, beloved author, professor of philosophy, America columnist, and member of the St. Louis University community, died far too young at 71. His influence went far beyond St. Louis, but he was rooted in this city. He leaves behind a crowd of witnesses at least in part because he loved and challenged all he met.

Once he came to dinner at my house along with my dad (a fellow St. Louis University High School and St. Louis University alumnus). I worried about what the author of Following Christ in a Consumer Society: The Spirituality of Cultural Resistance might say about my home in the suburb of Webster Groves. As soon as he walked in the door he said, "Prettiest house on the street!" immediately putting me at ease, and making me think again about whether I should move somewhere else.

I was drawn to Kavanaugh because of his profound critique of consumerism and injustice. When he rose to give a homily at St. Francis Xavier College Church, I would whisper to my three boys, "Listen. There's a prophet." Like many in College Church community, I valued the way he went right to the hard parts of Jesus' teachings, instead of explaining them away. He never let us off the hook.

In Faces of Poverty, Faces of Christ, he exposed the harshness of material poverty and told us, "Christ came not to bless this poverty, but to change it … to challenge all that would degrade and dehumanize human beings, to eliminate the grinding and blinding poverties that make us alien even from ourselves, that imprison and suffocate, that render us mute objects, that oppress and mutilate the spirit."

He challenged all who would listen to see and respond to that soul-crushing poverty that is not only far away but so close to where we live.

Though Kavanaugh's prophetic denunciations drew me in, what kept me coming back was something I wasn't initially looking for: his joyful embrace of human weakness. Over and over, he insisted,

We are not God. We are not full, not complete, not finished, not secure, not self-sustaining, not self-insuring. This lack is poverty, but a poverty which is blessed, pronounced good with all created being. We are not God, but we are good.

Though we try to run from this vulnerability, Kavanaugh kept gently urging his listeners to accept it, and then to enter more fully into the personal form of life, approaching solitude, friendship, family, and accompaniment of the marginalized just as we are. For in our vulnerability, we are loved and able to love.

Love and challenge drew people to Kavanaugh. On the Sunday after he died, College Church was filled. Longtime friend Jesuit Fr. John Foley presided. Jesuit Fr. Vince Hovley, another good friend, preached, speaking with warmth and gratitude of how Kavanaugh was the image of Christ for him.

Everyone else knew what he meant. The young students who had loved his classes. The Catholic Workers for whom he was a kindred spirit. The faculty from across the university who know his work was at the heart of their mission. Catholics working in every kind of organization devoted to social justice all over the city who were inspired by him. Alumni who had known him as a young, bearded Jesuit who said Mass in the dorms, gave great hugs, and jammed with the St. Louis Jesuits. Friends who remember the wonderful Kavanaugh family Irish music concerts. Parents whose weddings he celebrated and kids he baptized. Parishioners from College Church and St. Margaret of Scotland who made it a point to be there for his homilies. Men and women in religious life who cherished his example. They were all there.

Kavanaugh's last months were difficult, as he struggled with tuberculosis and bone marrow disease. In a blog devoted to giving updates about his progress, his brother Tom and sister-in-law Maureen wrote about his progress. In one post, they wrote that they wished they could say John was resting comfortably, but in reality, he was in a great deal of pain. Yet he shared with his family that he identified with the words of Pedro Arrupe, the late superior general of the Society of Jesus:

More than ever I now find myself in the hands of God. This is what I have wanted all my life, from my youth. And this is still the one thing I want. But now there is a difference: The initiative is entirely with God. It is indeed a profound spiritual experience to know and feel myself so totally in his hands.

One of Kavanaugh's best students, the photojournalist Mev Puleo, whose photos complement his reflections in Faces of Poverty, Faces of Christ, died at 32. In his homily at the funeral, Kavanaugh said that at the end of her life, as she struggled with a brain tumor, "she became the poor she loved."

Kavanaugh, too, embraced poverty and vulnerability at the end of life, leaving those who loved him with yet another image of comfort and challenge.

[Julie Hanlon Rubio is an associate professor of Christian ethics at St. Louis University.]