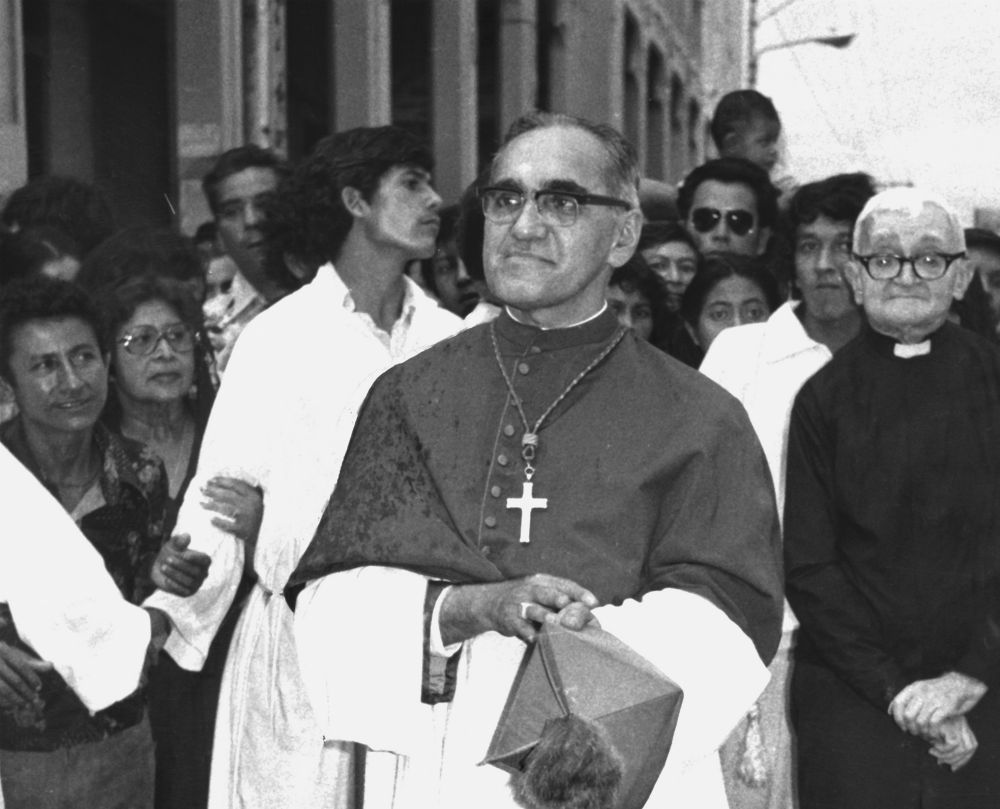

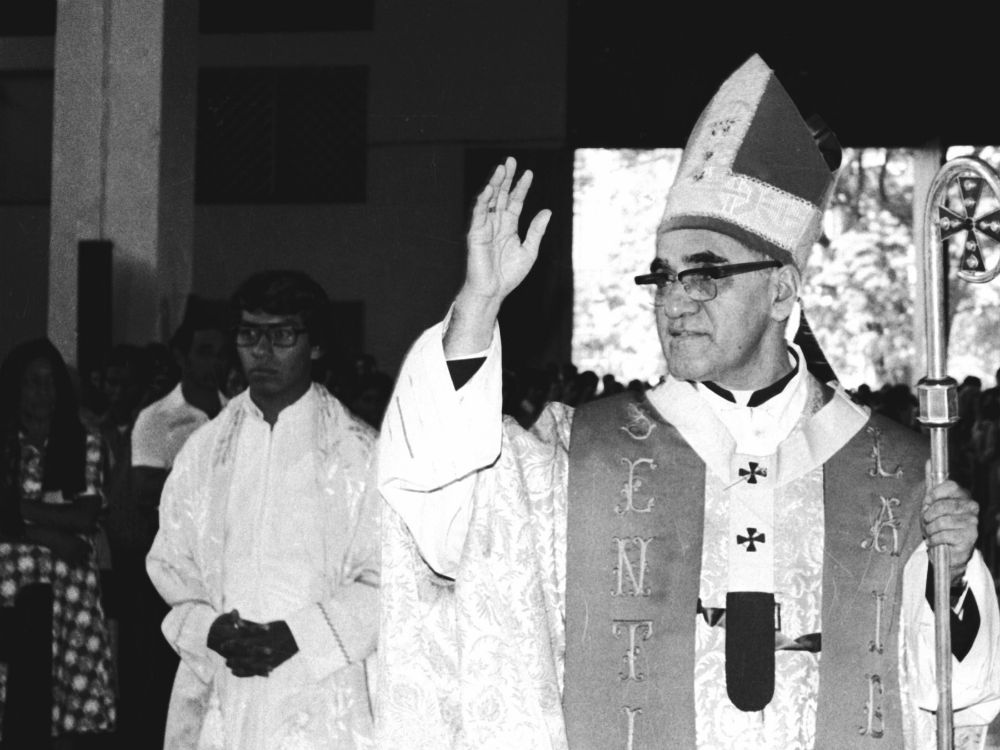

Blessed Óscar Romero is seen during a procession through the streets of San Salvador, El Salvador, in 1979. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero will be declared a saint later this year as Pope Francis has approved a miracle attributed to Romero's intercession.

Romero, who was shot dead while celebrating Mass in 1980, was influenced by the death of his friend, Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande, who was assassinated alongside two laypeople in 1977 after speaking out against the Salvadoran government.

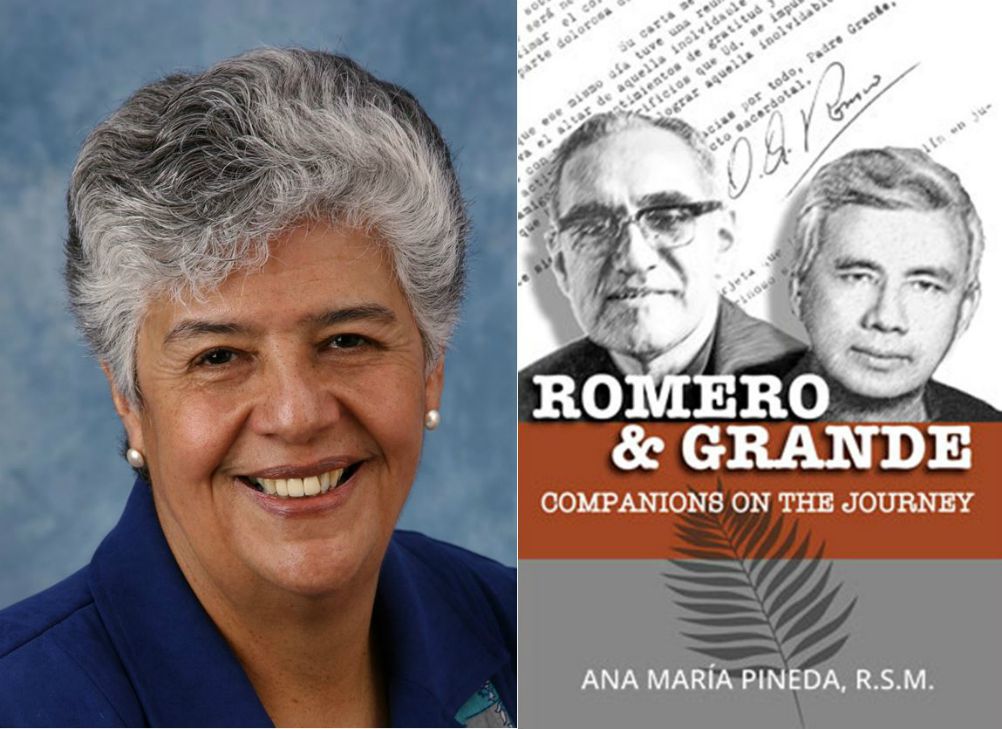

Mercy Sr. Ana María Pineda, a theologian at Santa Clara University, focused on the relationship between the two men in her 2016 book Romero & Grande: Companions on the Journey.

Pineda spoke about the friendship between the priest and the archbishop in a January NCR interview, during which she also gave details about Romero's spiritual life and considered the meaning of his pending sainthood for the global Catholic Church.

Following is that interview, edited for clarity.

Mercy Sr. Ana María Pineda, left, and the cover of her her 2016 book, "Romero & Grande: Companions on the Journey" (Sisters of Mercy, Lectio Publishing)

NCR: What do you think the canonization of Archbishop Romero signifies or says to the global church?

Pineda: I think his canonization affirms the importance of social justice in the church and what he stood for, and how it's important for us as Christians and as Catholics to be on the side of the poor … despite the difficulties, despite the challenges that might bring about.

For El Salvador, I think it affirms the fact that the way he lived his life and what he was doing was in fact what was Gospel. I think it's a tremendous affirmation of a Christian way of living that's manifested in Archbishop Romero's life.

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, the promoter of Romero's sainthood cause, has called him "a martyr of the church of the Second Vatican Council." What do you think that means?

I know Archbishop Romero had a tremendous love for the church and for the pope. He saw himself as being a faithful son of the church. The documents of the Second Vatican Council were extremely important to him. And he really understood them and lived them, and tried to follow what the council was indicating. I believe it was indicating a new way of being church and a way of being present in the world as the church, as a dialogue between the church and the modern world.

Advertisement

I'm not sure that he completely understood all its implications, but he followed the Second Vatican Council so closely. And for him it was the document from the church to follow. For a while he was even conflicted over the importance of Medellín. It took him a while to accept that Medellín was also an important church document.

Paglia has also said that it is impossible to know Romero without knowing Rutilio Grande. How do their stories fit together?

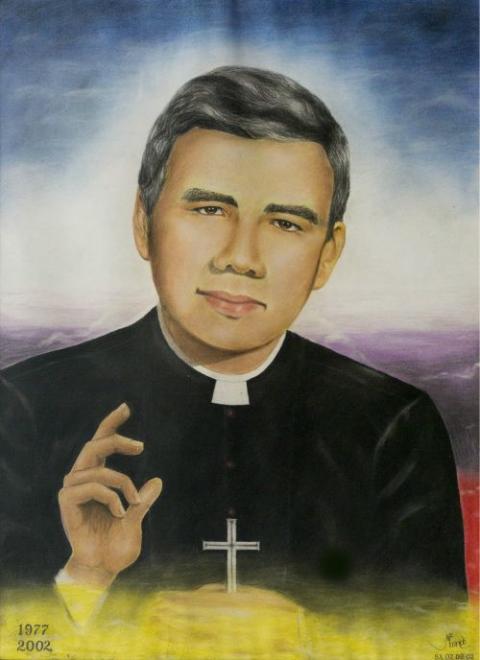

A painting of Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande is seen in the rectory of San Jose Church in the town of Aguilares, El Salvador. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

On this point, I probably hold a different perspective and thought [than others]. In the popular imagination and in popular devotion, the lives and deaths of these two men have been linked intimately. There is this very popular thought that when Rutilio Grande died that this created a dramatic moment of conversion for Romero, and that it was because of the death of Grande that Romero changes dramatically.

But in my research and in looking at Grande's archive, I get a less dramatic picture. From my perspective, Archbishop Romero, from his childhood, was a man in search of God and in search of the truth.

He's not a perfect man. Neither of them are. But in the midst of this, Romero is faithfully always looking for God, always looking for the truth and trying to become a better person, a better Christian, a better priest. And then he meets Rutilio Grande. But there's 10 years difference between the two of them, and they come from two different social backgrounds. Rutilio comes from a dirt-poor, little hamlet, El Paisnal. He's more toward the center of the country. And Romero is raised in Ciudad Barrios, in a working family.

In 1967, Romero is sent to San Salvador as secretary of the bishops' conference and lives at the seminary. According to what I have researched, it's there that there's a friendship that develops. But Rutilio is like the young brother to Romero. And he's the young brother that seems to provide Romero with more insight into the world because he was more progressive than Romero.

When Rutilio is killed, I think that's another piece in the journey of conversion for Romero and where he gets another moment of tremendous insight because he had great affection for Rutilio. And when he sees this man, who had a reputation for being a good man, he might have asked himself, "If they're killing him, this is saying something for what he was doing," which was defending the poor.

Rutilio is important to him and significant, but he's one additional part of his journey not the part of his journey.

"I think it's a tremendous affirmation of a Christian way of living that's manifested in Archbishop Romero's life."

—Mercy Sr. Ana María Pineda

In canonizing Romero, the church is also canonizing a bishop. What model do you think a St. Archbishop Romero gives to diocesan bishops? What does his life and witness teach bishops about how to be bishops?

I think the model for me has been that bishops are human beings, filled with goodness and fragility. Romero for me is a model of how one lives with that fragility and what one does with your humanity and your limitations.

Romero is very conscious of his limitations. He doesn't arrive to this preferential option for the poor, or any part of how he lives his Christian life, overnight. It's a journey. And if one were to read his spiritual diary, you see constantly how he's asking God to be a better person. He's asking God to please help him forgive, to be a more patient person.

I think he had little patience sometimes for priests, and so he would pray for patience: to be a better person, to treat them more kindly, more lovingly. He had a bit of a temper, which is hard to believe because what we see is the Romero of the last three years. His image and presence is very calm and tranquil. But apparently his temper is something he dealt with all his life. And I believe he was willing to ask for forgiveness when he realized he had done something that was incorrect.

He was willing to listen and to learn. I think that's what happened with Rutilio. They have fondness for each other, but Rutilio is a very progressive young priest, 10 years younger. And Romero is able to see in him perhaps what he doesn't quite have yet, and to learn from it and to listen.

I think all of us, whether we're bishops or not, we're called to that. We don't all have the answers. We all have human limitations of fragility. We all have to depend on the goodness of others to become better people in the world and to understand the needs of the world and where we're called as Christians. I think Romero's life is a wonderful model for bishops and for all of us.

Blessed Óscar Romero is seen in an undated photo. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

Romero's canonization comes at a time of incredible violence in the world. Pope Francis has spoken about a third world war, fought piecemeal. What message do you think Romero's sainthood gives to the world about the Christian witness of nonviolence?

I think it teaches us the ultimate need to respect humanity and human dignity, and the need for us to be creators of a world where everyone is seen as a brother and a sister on equal terms. And what we need to do in order to make that possible.

It's towards the end of Romero's life that perhaps you see the fruits of his labors, if you will, where he unconditionally gives himself to protect the most vulnerable and to be on their side. And this costs him a great deal because he was a timid man. He was very intellectually gifted, but he was a timid man. And yet he is emboldened to get up and to speak and to proclaim the need for us to be brothers and sisters to one another on equal terms and to make it possible for people to live a life of human dignity.

The treatment of the poor, or those who didn't have, he did it with tenderness and compassion. I think he, toward the end of his life, deeply learned the plight of the poor and what he needed to do as their pastor. And he even sometimes gave thanks that he was called to be the pastor of the suffering people, because that was what the church was called to be.

[Joshua J. McElwee is NCR Vatican correspondent. His email address is jmcelwee@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @joshjmac.]