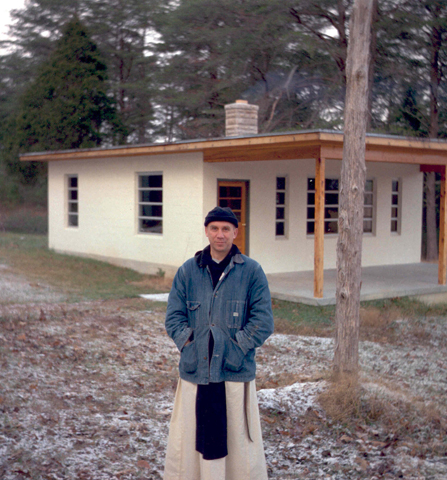

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in an undated photo (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

When Trappist monk Matt Torpey speaks of his mentor, teacher and friend Thomas Merton, the words flow like a gentle stream, befitting the memory of a Merton, a man well-known even in his own time and now recalled as perhaps the most influential Catholic writer of the 20th century.

Yet Torpey wonders if the man with whom he spent so many hours would recognize himself in the larger-than-life and occasionally hagiographic portrait that has been constructed in the years after his untimely death in 1968.

While Merton was funny, compassionate, widely read, loving, and sometimes touchy, Torpey said "being seen as a saint would kill him. They elevate you into another species. He was not another species."

Torpey, 87, entered as a monk at Gethsemani Abbey when Harry Truman was president. Torpey is also, even at a distance, a rather remarkable character. A longtime member of the community of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, Ga., he has suffered a number of medical setbacks in recent years, but the emergencies have done little to dim his puckish sense of humor or disarming candor.

"Life is very good," he said. "I've been very blessed."

Speaking of the man he knew so well, he said, "I want the guys [his fellow monks] to know how it was, but I also want the whole church to know it."

With a clarity undimmed by the years and an incisive recall of details, he conjures up a picture of a monastic era long past and sets in that context the prodigiously talented and yet very human Merton, a man Torpey said "had a most lively relationship with God."

Torpey entered monastic life in 1950. Those days before the Second Vatican Council included Latin Masses, stringent penances, almost-absolute silence, and a hierarchy in which the abbot made many, if not most, decisions on behalf of the community.

"I lived [in community] with Merton for seven years, and the first two in his daily presence were in absolute silence," Torpey said. "Basically, we used simple sign language. We did not really talk to each other. We did not talk at all without permission."

During the years that followed, Merton was both Torpey's "master of scholastics" (instructor to monks pursuing priesthood who had taken their first set of vows, known as temporary vows), as well as his spiritual director.

As Torpey recalls, Merton's lectures in the Flamingo Room (he had chosen to paint it pink) encompassed any topic that happened to be of interest to him, including not only the social issues of the day but more esoteric matters, like the significance of "cargo cults," an unusual religious practice that arose when South Pacific islanders encountered ships from Europe.

Merton also "liked to talk about guys who became saints when something went wrong in their situation ... unlikely people who became God's people," Torpey said.

Though Torpey treated his spiritual director with as much respect as he did his abbot, he said there would be times when Merton would say, " 'It looks like this,' and I'd say, 'I don't see it, but I probably will when I walk down the cloister now.' " Not infrequently, he said, he'd leave the session with Merton and have something occur to confirm Merton's insights. Merton also had a talent for mimicry, one he'd use occasionally to enliven their meetings.

Merton would sometimes be so overcome with the power of a Scripture reading, like the story of Jonah, that it would show despite all his efforts to hide it while listening to it at the Eucharist or during the daily office, Torpey said.

As popular as he was outside the monastery walls, Merton was not universally liked within them -- like "a prophet within his own household, not because of any fault, but here was a bunch of guys supposed to be hidden, away from the world, and here was this guy getting all sorts of attention," Torpey said. "We bother some people just by who we are."

Toward the end of Merton's life, his interest in Eastern religions grew, and he became involved in a romantic relationship he later renounced with a nurse, Margie Smith.

Torpey, by then a member of a Trappist monastery in another part of the country, had a chance to discuss Merton's feelings for the younger woman. As he and some of Merton's biographers see it, the relationship was a chance to resolve some of his feelings for women -- and a chance to experience being loved.

"I don't think he let himself feel love. That's huge," Torpey said. "Merton, like a lot of young guys, was a bit afraid of love, of this impulse to give ourselves to another. God creates use for love and aims it at himself, but not exclusively."

Sometimes, as Torpey puts it, God chooses to write with crooked letters.

"My opinion of Merton is that it was a helpful experience of being loved that he let himself have. As an old witness, I get the impression that it was a life-expanding experience," Torpey said, adding that he doesn't believe it "got very far."

"But the abbot at the time assured me that Merton wasn't going anywhere -- that wasn't Merton, and he wasn't going off with the nurse, and he wasn't going off to join the Buddhists. He knew that this [life as monk] was his vocation."

When Torpey heard of Merton's death in an accident involving an electric fan in Thailand, he could envision the monk's last moments: "He was a technological klutz."

But in the end, what defines Torpey's friend Merton was another kind of power -- that of a faithful but imperfect life.

"The man was compassionate, had a great sense of humor, was very human and wanted me to have life," he said. "He bestowed a lot on me."

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist at Lancaster Newspapers Inc. and a freelance writer living in Glenmoore, Pa.]