Irma Locasia holds a photo of her son Salvador Locasia Jr. in Manila, Philippines, Feb. 13, 2019. Her son was killed in a police operation on this street Aug. 31, 2016, a victim of the war on drugs of President Rodrigo Duterte. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

A Catholic bishop in the Philippines said his government's controversial war on drugs is really a war against the country's poor.

"There is no war against illegal drugs, because the supply is not being stopped. If they are really after illegal drugs, they would go after the big people, the manufacturers, the smugglers, the suppliers. But instead, they go after the victims of these people. So, I have come to the conclusion that this war on illegal drugs is illegal, immoral and anti-poor," said Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan.

The Philippines has suffered for years from widespread drug abuse, principally shabu, a cheaply produced form of methamphetamine. President Rodrigo Duterte ran for office promising a crackdown on drug use, and since he took office in 2016, rights groups say more than 20,000 people have been killed in extrajudicial killings, mostly carried out by the country's police.

Church leaders have grown increasingly critical of the violence. The country's Catholic bishops conference acknowledged in a Jan. 28 pastoral message that they had been slow in responding as a "culture of violence has gradually prevailed in our land."

The bishops spoke "of mostly poor people being brutally murdered on mere suspicion of being small-time drug users and peddlers, while the big-time smugglers and drug lords went scot-free." While they said they had "no intention of interfering in the conduct of state affairs," they said they had "a solemn duty to defend our flock, especially when they are attacked by wolves."

Duterte has repeatedly slammed the church in response to its criticism, and David, who also serves as vice president of the bishops' conference, has become the principal target of Duterte's angry outbursts at the church.

In November speech in Davao, Duterte said: "I'm telling you, David. I am puzzled as to why you always go out at night. I suspect, son of a bitch, you are into illegal drugs." At other times, he has accused the bishop of stealing church funds.

David has not turned the other cheek, instead responding quickly in social media posts: "I think it should be obvious to people by now that our country is being led by a very sick man. We pray for him. We pray for our country," he recently posted on Facebook.

Advertisement

"I think he picks on me because I'm quick in responding to his sound bites," David told Catholic News Service.

"I have discovered social media. I don't even have to talk to the media, they can follow the sound bites online. So, when he said that addicts are not human, I posted that I beg to disagree. I said no civilized society in this world would agree with him that addicts should be treated as nonhumans. And when he calls them nonhumans, does that mean we can do nothing about them except exterminate them? That's immoral. His statement had to be questioned. The problem is people don't question it, and when he repeats it over and over, it becomes gospel truth."

Duterte has often referred to drug users as "the living dead" as he justifies his policies.

"I think he has been watching too many zombie movies," said David. "It is a kind of 'othering,' labeling them so that when they are found dead on the streets, people will be happy and respond, 'Good, that's one criminal less.' "

David said he is becoming increasingly desperate as he hears cries for help from the urban poor communities in his diocese. He has complained publicly about mass arrests of people without warrants and has criticized police detention without charges of young children who he said are kept in cages for weeks as their parents attempt to have them freed.

"Sometimes I have a feeling that we are back in the Nazi days, when people are somehow aware of what's going on, but they play deaf and dumb because they also like what's happening, because they are persuaded by the sound bites that this is the best way to get rid of criminality. You can get rid of criminality through criminal means? If that's true, then you have created a criminal government," he said.

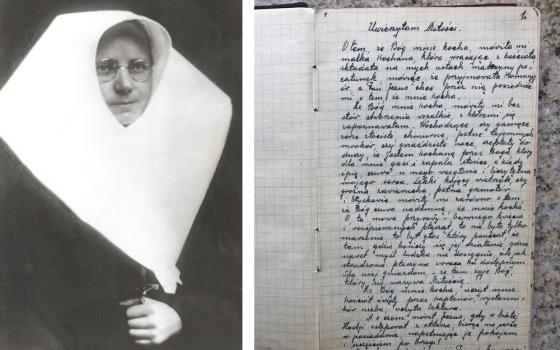

Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan, Philippines, pictured in a Feb. 15, 2019, photo, says his government's controversial war on drugs is really a war against the country's poor. David also serves as vice president of the bishops' conference. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

While his diocese has responded to the crisis by working with some local governments to set up an effective community-based drug rehabilitation program, David said the war on drugs has pushed the church even further, forcing it closer to the side of poor communities that bear the brunt of arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial killings.

"The war on drugs got me closer to the poor. Maybe that's the blessing of it. It's so easy for bishops and priests to just go through the motions of doing our jobs, jobs that are institutionalized and defined for us. Our parishes are old and tired institutions that cater to church-going people, just the usual people. Our access to the poor is really the big challenge for us," said David.

Although Sunday Masses at the cathedral parish in Kalookan are standing room only, David said the church is reaching just a fraction of the people in his diocese. Instead of starting new parishes, which he said is cumbersome, expensive, and takes time, he has opened mission stations in the slums of his diocese, staffing them with religious from around the world.

"We are getting acquainted with the poor because of our mission stations. These are not parishes, but rather the church being present among the poorest of the poor. We have mission partners who I ask to live right there in the slums, among the poorest of the poor, so that the church will be accessible, so that the church will have quicker access to the poor and their needs," he said.

David said those mission workers keep him directly informed of arrests and killings and have even witnessed extrajudicial executions. They also frequently appeal to the bishop to intercede with officials on behalf of detained children.

"Our mission stations are like new wine bursting the old wineskins," he said. "Pope Francis keeps talking about going to the periphery, and this is the perfect opportunity. A mission station is a church without a church building, without a chapel. I send missionaries to live with them and they do community organizing and set up basic ecclesial communities. The sense of community is going down here in the city. There is no common ethnicity nor common language nor common origin. All of these people have migrated from the different provinces, and so they are strangers to each other. Who will build them into a community? They are very transient, they come and go, looking for where they can find jobs. Our role is to build community among them."