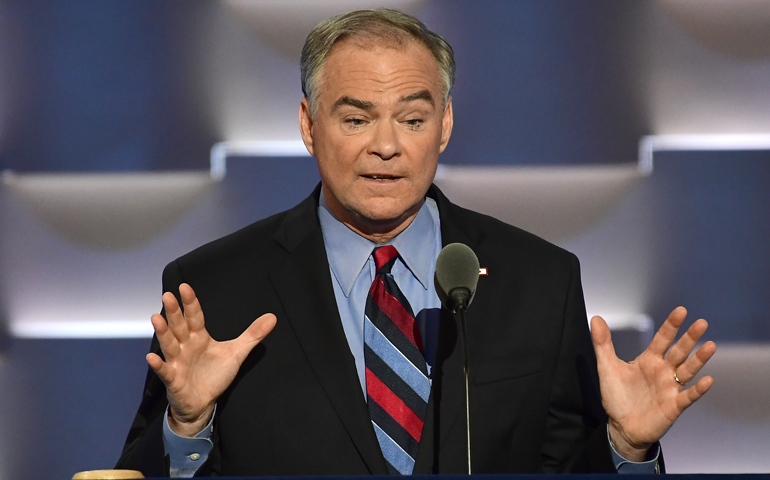

Sen. Tim Kaine (Democrat of Virginia) makes remarks accepting the Democratic Party nomination for Vice President of the United States during the third session of the 2016 Democratic National Convention at the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on Wednesday, July 27, 2016. (Ron Sachs/CNP)

Tim Kaine has got the faith.

Faith in God and the Catholic church. Faith in Hillary Clinton leading the Democratic presidential ticket. Faith that after a heated and divisive election cycle the U.S. can still locate common ground on major issues -- including jobs and immigration -- that would signal the nation is more united than divided.

For Kaine, a self-described optimist, the first step, come January, must start at his current place of employment: Congress.

"That's really where the rubber meets the road," the Democratic vice presidential candidate told NCR in a sit-down interview Aug. 17 in the Kansas City suburb of Overland Park, Kan. "But some strong work early, on areas where there is likely to be common cause, might be a way we can start speaking to people who feel divided."

As predicted by his chief of staff, Kaine, 58, arrived early for the morning interview, the last item on the Kansas City agenda before taking the campaign trail westward. The quick visit in town served as part fundraiser, part homecoming -- his first visit back to the region since accepting the Democratic vice presidential nomination. He reunited with his friends from his Jesuit high school, forgoing the confines of a night in a hotel for the comforts of a bed at his parents' home.

The Virginia senator and former governor arrived to the 2016 presidential election largely unknown.

But the first few weeks after becoming a veep nominee revealed some details about Clinton's new right-hand man: He’s fluent in Spanish (a credit to his missionary year in Honduras); he plays the harmonica (and has pulled it out on the campaign trail, including at a North Carolina brewery); and he's comfortably, in his own words, "boring," illustrated even more through the sitcom dad persona and #TimKaineDadJokes that sprung up on social media following his speech on the third night of the Democratic National Convention ("i bet if tim kaine has leaked voicemails at the DNC they were all reminders to stay hydrated" was one popular tweet).

Tim Kaine thinks the leather wallet you made in that crafts class is pretty cool. https://t.co/MPlEZlH94Y

— Jim McDermott (@PopCulturPriest) July 28, 2016

In an election so far defined by who's hurled (and received) the worst insults, which party is more torn or disconnected, and why, in an examination of the American psyche, so many so dislike the presidential candidates, Kaine comes across as a politician apart.

Kaine, too, has his political flaws. As lieutenant governor and governor of Virginia, he received $160,000 in gifts. (All were determined legal, properly publicly disclosed, and primarily used for work-related travel expenses.) As mayor of Richmond, Va., his compromise solution over a racially contentious mural didn't satisfy everyone. (It was eventually burned down.) And he has received criticism from both the right, for his high rating with Planned Parenthood, and the left, for the 11 executions he oversaw as governor, despite being personally opposed to both abortion and capital punishment.

On the campaign trail, like all running mates before him, Kaine has extolled the positives of his party's candidate, taken shots at the opponent, and shared who he is. That latter has often had him talking about his Catholic faith.

"What I've tried to do is be a religious person and just share who I am with people. Not to proselytize, not to make them be who I am … because if I tell people I like to play the harmonica, and I like to camp, I got three kids, I'm married, why wouldn’t I share what's the most important thing to me?" he said.

Kaine is the third Catholic to appear on a presidential ticket in the past two election cycles, all VP nominees. (Current Republican vice presidential candidate Mike Pence was raised Catholic but now identifies as an evangelical Christian).

In 2008, Joe Biden said that while others may talk about his faith, he seldom does, instead driven by his Irish upbringing to allow his actions to speak for themselves. Four years later, Paul Ryan was greeted with a chorus of criticism in 2012 for his interpretation of Catholic social teaching to justify a budget proposal that included deep cuts in programs assisting the poor.

And it was John F. Kennedy, the only Catholic to win the presidency, who in 1960 responded to questions of papal influence over his decision-making by famously saying, "I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic." Kennedy added, "I believe in a president whose religious views are his own private affair, neither imposed by him upon the nation, or imposed by the nation upon him as a condition to holding that office."

Rather than bury it or force it on others, Kaine said he chooses to share his faith as insight into his motivations in a life of public service, but also to allow people -- and voters -- to understand how he might approach an issue, whether the economy, foreign policy or another yet to rise to prominence.

"I think when we share our own spiritual insights, our motivational insights, it's kind of a Teilhard de Chardin principle -- that everything that rises must converge, that's all wisdom building on each other and it makes us all smarter. So that's kind of the way I've tried to do it," he said. "Neither walling it off nor mandating it, but just sharing my motivation in the hopes that others will share theirs and they can learn from me and I can learn from them."

'Maybe I can figure it out'

By now, the story of Tim Kaine's Catholicism has largely come into focus.

He was raised in a working-class Irish family that rarely missed Mass on Sunday. He attended the Jesuit-run Rockhurst High School in Kansas City, Mo., where the "men for others" motto became a huge influence on his faith formation, as well as his public life. After finishing in 1979 an economics degree from the University of Missouri in three years (he at first entertained journalism), he enrolled at Harvard Law School, only to temporarily step away to spend a year (1980-81) as a missionary with Jesuits in Honduras.

"I went to Honduras because I didn’t know what I wanted to do and everybody in law school seems so sure, and I figured, well, if I take a year off maybe I can figure it out," he said.

Kaine did.

Profoundly moved by his experience in Central America -- where he witnessed extreme poverty while a military dictatorship, with U.S. training, kidnapped, tortured and killed civilians -- and now fluent in Spanish, he decided to apply his legal skills toward twin goals: social justice and racial reconciliation. The two first came together in his 17 years as a civil rights lawyer in Richmond, Va., working on housing discrimination.

As Kaine witnessed life under a military regime, which cracked down on the Jesuit priests he would later call "the heroes of my life," he left with greater awareness of inequity in his own country. Martin Luther King Jr.'s description of 11'o clock Sunday morning as "the most segregated hour in America" in particular spoke to him, and also rang true of his own Mass experience back home.

When Kaine arrived in Richmond in 1984, he and his soon-to-be-wife, Anne, daughter of former Republican Virginia Gov. A. Linwood Holton Jr., joined St. Elizabeth Catholic Church, a predominantly African-American parish where they were married later that year and still remain parishioners.

The worship environment at St. Elizabeth, influenced by the neighborhood's Baptist and Protestant roots, transported Kaine back to Honduras, where he had fallen in love with a Mass structured less around keeping a schedule and more around communal prayer.

"I was used to going to Mass where it was 45 minutes because they had to clear out the parking lot ahead of the next Mass. So cut and dry," Kaine told David Gregory on his podcast in May. "But in Honduras, there would be two weddings, three baptisms, the kiss of peace would last 15 minutes, kids and chickens would be everywhere. But it was just so full of life and not organized and kind of chaotic, but chaotic in a beautiful way."

The parish has become the heart of Kaine's spiritual life. He's also a regular at the U.S. Senate's Wednesday morning prayer group. Although a proponent of the separation of church and state, he told NCR he sees parallels between the two:

"Neither faith nor politics would exist if humans didn't have an instinctive belief that what is is not as good as what could be. If we didn't perceive the gap between what is and what could be, there wouldn't be religion and there wouldn't be politics, either. But it's our awareness of our own imperfections and our instinctive understanding that society can be better and I can be better. That's why it's the gulf between the is and the ought that is where both religion and politics come. And that is an instinctive reaction that we have, and I view that as, that is a divine question mark that's put into every person, that from some point in early age we start to be able to perceive that what is isn’t as good as what could be, both individually and in society. And so that's the deep connection, I think, between religion and politics done right."

Measured by the Catholic yardstick

Beyond insight into his motivations, Kaine says that sharing his faith also provides people a yardstick to hold against him, a way to see how he measures up and when he falls short.

The yardstick has received ample use throughout his 22-year political career, one in which, he proudly touts, he is 8-0 in winning elections.

When news broke of his selection as Clinton's running mate, Catholic social media buzzed about his faith in action. A popular hive was abortion -- which despite its factious nature is largely a non-voting issue for most Catholics. (Among all voters and Catholic voters, it ranks behind a dozen other issues, according to Pew Research Center.) While Kaine has voiced his personal opposition to abortion, he has 100 percent ratings from Planned Parenthood and NARAL Pro-Choice America.

In June, he told "Meet the Press": "I deeply believe, and not just as a matter of politics, but even as a matter of morality, that matters about reproduction and intimacy and relationships and contraception are in the personal realm. They're moral decisions for individuals to make for themselves. And the last thing we need is government intruding into those personal decisions. So I've taken the position, which is quite common among Catholics. I've got a personal feeling about abortion, but the right role for government is to let women make their own decisions."

Pro-life critics skewered the stance as trying to have it both ways. Richmond Bishop Francis DiLorenzo released a statement shortly after the veep announcement that the Catholic church makes clear to elected officials that all human life is sacred from conception to natural death, and that every Catholic must decide "their worthiness" to receive the Eucharist.

Less subtly, a Dominican priest tweeted to Kaine, "Do us both a favor. Don't show up in my communion line."

Senator @timkaine: Do us both a favor. Don't show up in my communion line. I take Canon 915 seriously. It'd be embarrassing for you & for me

— Fr. Thomas Petri, OP (@PetriOP) July 24, 2016

Kaine was able to extinguish some of the abortion backlash among pro-life Democrats by reiterating his support of the Hyde Amendment -- passed in 1977, it blocks federal funds from paying for abortions -- despite the Clinton and the Democratic Party platform supporting its repeal.

Even with the Hyde repeal in the Democratic platform, Kaine sees space for pro-lifers in the party, and that neither the Republican nor the Democratic Party is right about everything. Among Democrats, he said he commonly sees examples of the good Samaritan -- people who respond to a neighbor in need. The attitude of Democrats toward party platforms is akin to Catholics toward church doctrine: There's rarely unanimity among all members.

"How many of us are in the church and are deeply serious about our faith and agree with 100 percent of church doctrine? I would argue very few Catholics are in that position. We’re all working out our salvation with fear and trembling. We love the Catholic church, I know I do, I'm very serious about it. I'm not going to say I'm a good Catholic or a great Catholic, but I know that I'm a better person because I'm a Catholic," he said.

Then there's the death penalty.

"The hardest thing about being a governor was dealing with the death penalty," Kaine told NCR. "I hope on Judgment Day that there's both understanding and mercy, because it was tough."

As Virginia’s 70th governor (2006-2009), Kaine oversaw 11 executions. In each case, he personally opposed capital punishment but held fast to his perceived moral obligation to his oath to uphold the law -- even laws he disliked.

In one case, Kaine granted clemency, believing the man had mental health issues, but he refrained from the temptation to use the policy as a way to in effect eliminate the death penalty in a state that is behind only Texas and Oklahoma in executions since 1976. When the Virginia Legislature sent him bills expanding the death penalty, he vetoed them. His staff at the time described the governor on days of executions as quieter and withdrawing to his office before they began, where they believed he was praying.

Before entering politics, Kaine took on two pro-bono capital punishment cases. In one case, he shared his client’s final meal with him, had a priest come to celebrate Mass, and walked the client to the death chamber, holding his hand as he was strapped to the table.

Kaine has spared no words about his desire to see the death penalty die, and is encouraged that Clinton, though she has not called for its end, has "expressed great reservations about it in implementation and that way that it's used." He sees the American public, through juries issuing death penalty sentences, largely in line with that view.

"For there to be an end to the death penalty in the United States, it’s going to have to be because the public decides, you know what, we just really don’t need to do it," he said. "Other nations don’t do it. Americans aren't worse than other nations. The nations that have the death penalty aren't the ones that we want to be on the same lists with. And I do see some evolution in that thinking."

Francis' challenge to Congress

Statements on the sanctity of life and the death penalty brought differing factions of Congress to its feet when Pope Francis uttered them in his address to a joint session last September as part of his first-ever visit to the United States.

The junior Virginia senator opted to remain in his seat for it all, his hands muted except for applause at the beginning and the end.

The experience, Kaine would tell a Georgetown University audience days later, "brought tears to my eyes." Seeing a Jesuit pope from Latin America resurrected memories of his friends in El Progreso, Honduras, some of whom after Kaine's departure were jailed or killed. He would love nothing more than someday (and after the election) to sit down with Francis and talk about those priests, whom he suspects the pope may recognize, not personally but through their similarities to clergy that Jorge Mario Bergoglio knew in Argentina during its political upheaval.

"It was a tremendous honor to be in the chamber," Kaine told NCR.

Ahead of the papal visit, Kaine, along with other members of Congress, had responded to a question from NCR about what they hoped to hear from the pope. The senator responded in part, "There is nothing this pope could do that would improve the world as much as putting the church on a path to ordain women."

While he accepts church teaching on women's ordination, it's one area where Kaine prays a change may eventually come. He was happy when the pope in early August announced the commission to study the issue of women deacons, what he viewed as a first step forward.

"I think as long as women in the great world religions are treated in any kind of a second-class way, then it provides justification for treating women in a second-class way in earthly matters, too. And I just feel that very profoundly," Kaine said in the interview.

The decision by Francis to choreograph the congressional speech around four Americans -- Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day and Fr. Thomas Merton -- in particular spoke to Kaine.

"He was holding up people with very obvious flaws who through the grace of God didn’t shed their flaws but could transcend them. And that’s what we’re called to do," he said.

He told the Georgetown event that the pope's words on abortion and the arms trade particularly spoke to him -- the challenge of deciphering the degree to which church teachings on sexuality are doctrines on personal behavior or warrant passing laws applicable to people of different religions; and the challenge, as a member of the Armed Services Committee, of deciding how to provide weapons to nations with legitimate defense needs but avoid the transaction becoming, as Francis described it, "drenched in blood, often innocent blood."

More broadly, he heard Francis deliver a powerful challenge to Congress to recognize America’s many past achievements and to find the collective will to address the global challenges of the present and future. In a time when public sentiment toward Congress nears historical lows, the pope arrived "to set high expectations," Kaine said, "not only for us but through us to the American public."

The senator with a penchant for bipartisanship is convinced that even in the current political climate -- one he sees as having the most divided electorate since the post-Watergate and post-Vietnam 1976 election -- that high bar can be reached.

Kaine said Clinton is "very mindful of this," and the two have discussed how they might address Washington gridlock should they take the White House in November. Part of that is campaign strategy: draw clear distinctions with the GOP but don’t needlessly trash motives. A larger part is selecting the issues where consensus can develop early on. The optimist Kaine sees Clinton's 100 days priorities -- grow jobs in the economy, place immigration reform back on the table, and reform the political system -- as a way forward, all of which he referred to as inclusion goals.

"We have to really look for opportunities to focus on areas where we can find agreement. There's plenty where we don't agree, but we can save those debates for later. Let's start out by focusing on some areas where we do," he said.

Any chance to reach compromise in Congress would likely involve some level of intervention by the vice president, who presides as president of the Senate. And however the two chambers go Nov. 8, Republican votes. Kaine spoke of the respect he has for the willingness of Speaker of the House Ryan to negotiate, pointing to the 2013 bipartisan budget deal he reached with Sen. Patty Murray (Kaine is on the Senate budget committee). Others have spoken of Clinton's ability as a senator to work with those who largely opposed her or her husband.

Kaine has faith that early consensual action could demonstrate to the American people that the federal government may not be broken and the nation not so divided. But that happening may also require an assist from the faithful, as he believes an important role exists for religious communities to not only model civil dialogue amid differing views, but to command it from its legislators.

"Our churches in this country are strong voices for themselves but they've also tended to be strong voices for pluralism and civility. And we really could use that now."

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]