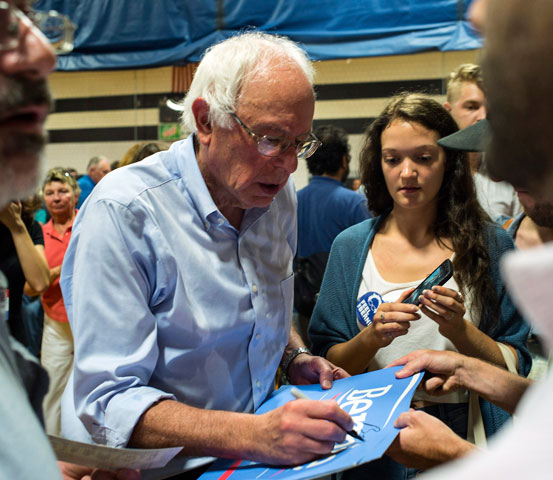

Sen. Bernie Sanders signs autographs during a town hall meeting in Conway, N.H., Aug. 24. (Newscom/EPA/CJ Gunther)

Bernie Sanders is a climber -- not a social climber, for sure, but a poll climber, rising steadily as his unapologetic liberalism attracts donors with money and supporters with zeal. Within hours of announcing his campaign for the presidency, $1.5 million poured in, most of that in small sums, and 175,000 volunteers signed up. Polls now show him besting Hillary Clinton, with the rest of the Democratic field gasping in the air of irrelevance.

Amid the slew of pandering Republican mediocrities and flameouts seeing themselves as the next president, Sanders could have half the mother wit and moral power that has long marked his politics and still be a singular force for true reform. His net worth is $330,000, that in a current Congress where for the first time, reports the Center for Responsive Politics, more than half its members are millionaires. When debating food stamps, the minimum wage, and unemployment benefits who is closer to those realities: the congressional moneyed class or someone like a shallow-pockets Sanders?

With that as a financial reality, it's no surprise that the junior senator from Vermont is warning that the United States is a "plutocracy." There he is, nesting on the Senate floor amid his well-fixed colleagues as they loophole tax laws favoring the richest of the nation's rich, themselves included.

"Think about the working elderly," Sanders suggests, "people 60 to 65, who have worked their entire lives to put away a few bucks for a dignified retirement. [Now] some of them are packing groceries in supermarkets and wondering how they are going to heat their homes this winter."

The income inequality gap grows. The Progressive magazine states: "In 1970, the ratio of the top 100 corporate CEOs and the average worker's pay was 40 to 1. Today it is 331 to 1, with the average CEO earning almost $1 million a month."

Few others at the highest levels of American politics can speak with the credibility of Sanders when the issue is money and how it is legislatively spent: "Very often at budget hearings," he told The Washington Post in June, "you will hear me say as the major deficit hawk in the committee — and I refer to myself as that because I voted against the war in Iraq, I voted against tax breaks for millionaires, I voted against the Medicare prescription drug program, I voted against the deregulation of Wall Street, which has caused so many problems. … I'm a deficit hawk when I say we have to ask the wealthiest people and the largest corporations to pay their fair share. That's a deficit hawk."

I go back a ways with Sanders. I interviewed him in the early 1980s, not long after he became the mayor of Burlington, Vt., with a pebble-slide victory of 10 votes. Personable, he was politically astute and able to joke about his supporters being labeled Sanderistas. We talked about his pre-Vermont days in Brooklyn, N.Y., and his intellectual kinship with socialist presidential candidates Eugene Debs and Norman Thomas and how their unthinkably wild calls for workers' rights, paid vacations and fair wages would became standard political fare.

Dismissed by establishment elites as an electoral fluke, Sanders became a get-it-done mayor who filled potholes, worked the neighborhoods, remembered names, and other sprucings of local politics. He brought in a minor league baseball team, the Vermont Reds. Well, it could have been the Vermont Trotskys.

In the interview, I don't recall either of us predicting that he would rise from a small-town mayor to serving more than 25 years in the House and Senate, and all the while giving fits to no-spine centrists forever needing their bluffs called.

In the mid-1990s, we met again, at Goddard College near Burlington where Sanders' wife, Jane, was the provost and had invited me to speak to the students. Sanders, in town, came to the talk. It wasn't the best use of his time, if I may self-deprecate, but he endured my gab graciously as I tried to outliberal the stoutest liberal in Congress.

Of late, crowd turnouts at Sanders' rallies have been getting larger. A yearning is present, one as stirring and authentic as the good man arousing it.

[Colman McCarthy, directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, D.C. His recent book is Teaching Peace: Students Exchange Letters With Their Teacher.]