The Christ the Redeemer statue is lit up with an image of Pope Francis to mark the launch of his book, “Life: My Story Through History,” in Rio de Janeiro, May 23, 2024. (AP/Silvia Izquierdo)

In major Latin American countries, Catholic support for ordaining women as priests has risen significantly in the last decade, while Pope Francis’ popularity has declined somewhat, according to a survey released Thursday (Sept. 26) by Pew Research Center.

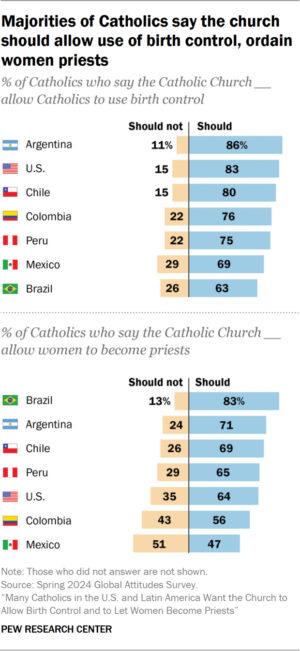

Peru saw the highest increase among the surveyed countries — which also included Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico — with 65% of Peruvian Catholics supporting the ordination of women priests, up from the 42% average across three surveys taken between 2013 and 2015. Brazil saw the smallest jump but also maintains the highest overall support, with more than 8 in 10 Brazilian Catholics in favor.

Pew’s poll, which surveyed Catholics from across six countries that together account for roughly three-quarters of Latin America’s Catholics, gauged attitudes on Pope Francis, women’s ordination and a host of other church reforms. It also compared those responses to the results of a February survey of U.S. Catholics.

After Peru, Mexico saw the highest jump in support for women’s ordination, with an increase of 16 percentage points (31% to 47%). Support went up 13 points in Colombia (43% to 56%), 20 points in Argentina (51% to 71%), 6 points in Chile (63% to 69%) and 5 points in Brazil (78% to 83%). In the U.S., support for women’s ordination was stable across the decade, at 62% and 64%, according to the February survey.

Younger Catholics across Latin America are more likely to support women’s ordination to the priesthood — except in Brazil, where support is equally high across generations — whereas in the U.S., Catholics over age 40 are more likely (66%) than their younger counterparts (57%) to support women’s ordination. The largest generational gap is in Mexico, where 64% of 18- to 39-year-olds support women’s ordination compared with 34% of those 40 and older.

The survey also found that Francis’ popularity has dropped throughout Latin America in the last decade, though significant majorities of Latin American Catholics still view him favorably. Currently, Francis enjoys the highest popularity in Colombia, where 88% of Catholics view him favorably, down from 93% a decade ago. He is least popular in Chile, where his favorability among Catholics has fallen 15 percentage points over the past decade (from 79% to 64%).

The majority of the general population in the Latin American countries surveyed, which includes non-Catholics, continue to view Francis favorably — with the exception of the Chilean population, among whom his favorability hovers around or just below half (48%).

The Rev. Gustavo Morello, a Jesuit and professor of sociology at Boston College who studies Latin America, said that despite some declines the relative popularity of Francis, also a Jesuit, surprised him.

"I couldn’t find any other ranking of a leader who has been in charge for the last 10 years that has a better image than the pope," Morello told RNS, noting that only some dead U.S. presidents did better in opinion polls. "It’s a sign of the lack of global leadership," Morello said.

Morello believes local experiences impact each country’s view of Francis, pointing to both politics and church scandals in the various countries.

Majorities of Catholics say the church should allow use of birth control, ordain women priests. (Courtesy Pew Research Center)

In Chile, which has seen recent political turmoil over proposals for constitutional reform, the church has also experienced a significant clergy abuse crisis. In 2018, Francis provoked angry protests when he defended a bishop accused of participating in a cover-up, before eventually accepting the bishop’s resignation. These events may impact Francis’ low favorability, Morello said.

In Colombia, Francis backed a peace deal between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia guerrilla group, or the FARC, which may have contributed to his popularity, Morello said.

Francis saw his greatest drop in popularity in Argentina, his home country, going from 98% favorability among Catholics a decade ago to 74% favorability in 2024. His favorability in the general population is at 64%, down from 91% a decade ago.

Morello said that his research from 2015 and 2016 in Argentina shows that support for the pope is nuanced.

Interviewees have told him they supported Francis’ intervention at the international level with institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Economic Forum because they felt voiceless in those places. (The IMF has held a substantial amount of Argentine debt.)

However, they told Morello they disliked when the pope weighed in on national politics in Argentina, where they could vote and felt he was taking power away from them.

Francis’ loudest critics have often been those who say he’s made too many changes in the church, yet Pew’s poll found that Latin American Catholics who viewed Francis very favorably were more likely to say he represented a major change than those who viewed him less favorably.

The poll also asked for Catholics’ views on a number of church teachings, including on contraception, receiving Communion while unmarried and living with a romantic partner, married priests and gay and lesbian marriages.

Significant majorities of Latin American Catholics support allowing contraception despite the church’s official stance against it. Argentina had the highest support, with 86% of Catholics supporting contraception. Although Brazil was most in favor of church reform on women priests, it was least in favor of allowing contraception, with only 63% of Brazilian Catholics supporting it.

Support for birth control rose in every surveyed country over the last decade, except in Chile, where there was a slight drop (from 83% to 80%), and more dramatically in Brazil, where support dropped 12 percentage points (from 75% to 63%).

Similarly, majorities of Catholics in every country surveyed except Mexico supported allowing cohabiting romantic couples to receive Communion. Argentina was most supportive, with 77% of Catholics expressing support, while only 45% of Mexican Catholics said the same.

Advertisement

Smaller majorities of Catholics in Argentina, Chile and Colombia support allowing married priests, ranging from 65% (Chile) to 52% (Colombia). Half of Brazilian Catholics support married priests, while only 38% of Mexican and 32% of Peruvian Catholics say the same.

Support for married priests either rose or remained the same in every Latin American country surveyed, except for Brazil, which saw a 6-point drop (from 56% to 50%). (While a small number of Catholic priests are allowed to be married, the vast majority are not.)

Only Argentina (70%) and Chile (64%) had Catholic majorities who supported recognizing the marriages of lesbian and gay couples. In the other countries surveyed, support ranged from 46% of Catholics in Mexico to 32% of Catholics in Peru.

Across these church reform measures, Pew’s researchers wrote that Catholics who pray daily were less likely to support reform and that, where the sample size allowed analysis of frequent Mass attenders, frequent Mass attendees also were less likely to support reform measures.

This survey was the second that Pew released using a new survey method that focuses on asking similar questions in select countries in order to allow for broader comparison across the world. The questions in this survey were similar to those asked in the U.S. in February.

Previously, Pew had designed surveys around specific regions. In the Latin America survey a decade ago, more countries were surveyed, and there were more region-specific questions.

Jonathan Evans, the senior researcher who led the report, explained that Pew used a face-to-face method in Latin America, where a mix of urban and rural places are randomly selected. Then, depending on the size of a location, researchers will have a pattern to follow for which doors to knock on, for instance, every fifth door, where an adult household member will be randomly selected to participate. If that adult is unavailable, the researcher tries to reach that adult another time.

Morello cautioned that door-to-door methods may miss the wealthiest, given that they may live in gated communities, and the poorest, who may live in areas hard to access. Nevertheless, he praised Pew’s methods. "I don’t have any fear about the methodology. In any case, if they couldn’t do this, nobody can," the priest and sociologist said.The survey collected responses from 3,655 Catholics in Latin America from January to April of this year. In the six Latin American countries, the margin of error ranged from plus or minus 4.9 percentage points to 6.0 percentage points.