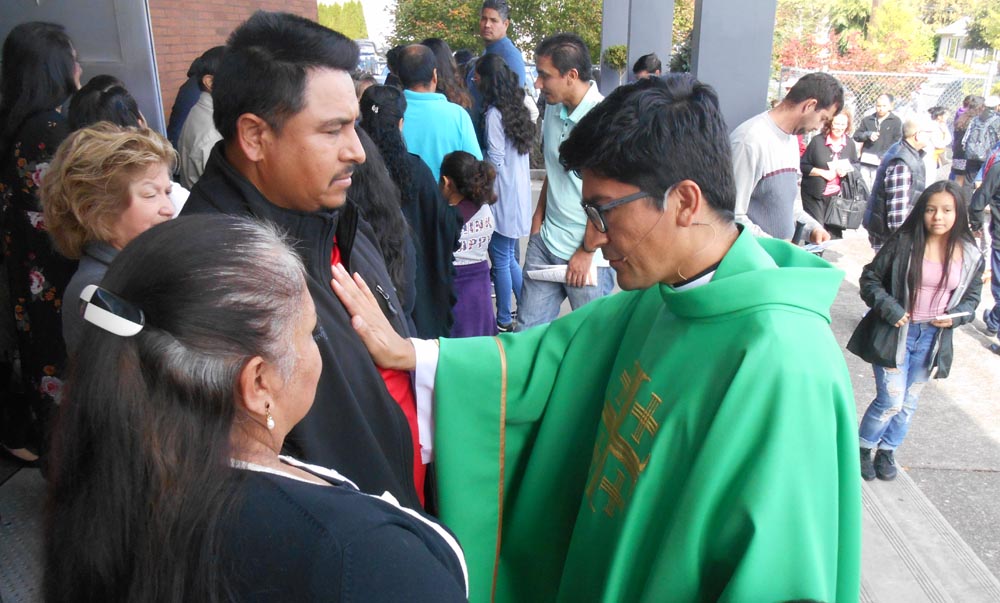

Fr. Raul Marquez outside St. Peter Church after a Spanish Mass, in Portland, Oregon (Peter Feuerherd)

When a handful of men marched in front of St. Peter Church here during a Sunday Spanish Mass in January, they scored a strange and threatening trifecta.

Calling themselves Christians, the men scolded women going into church for their appearance, claiming it was overly provocative. They voiced displeasure with both the Catholic Church and the Mexican-American presence at St. Peter.

A child in first Communion class said she was scared. Older parishioners expressed both fear and bewilderment.

The next week, something unusual happened. Thanks to social media, the word got out about the demonstrators. In this mostly secular, largely non-Catholic and white city, about 200 counter-demonstrators appeared. They expressed support for Mexican-Americans and their right to practice their Catholic faith peaceably. The anti-Latino, anti-Catholic and anti-women demonstrators didn't show then and haven't been seen at the parish since.

Fr. Raul Marquez of St. Peter Church in Portland, Oregon, thanks people who came to stand vigil outside his church Feb. 5. The crowd formed a human shield a week after a group of eight men stood outside the front door of the church during a Spanish Mass and yelled insults about Catholicism, immigrants and the morals of the parish women. (CNS/Francisco Lara, Catholic Sentinel)

"It was amazing to see," said Dinorah Jimenez, a volunteer catechist and parish secretary. The result of the fracas was ultimately positive, she said, noting that the publicity helped attract new parishioners and the spirit of the parish solidified.

In some ways, the show of support here was not unusual. This is an anti-Donald Trump city — Hillary Clinton won here by a 3-to-1 margin. While it is the whitest large city in the U.S., with a relatively small minority population, it's not unusual to see Black Lives Matter signs on the lawns of Portlanders. They revel in diversity, with a popular slogan being "Keep Portland Weird."

On Oct. 11, a group of Portlanders were arrested for standing in front of an ICE bus filled with immigrants being sent to a detention center for deportation.

But what happened at St. Peter extended far beyond this city. Letters came from around the world expressing support once the story hit the internet. Parishioners appreciate the widespread resistance to the hate-filled demonstrators.

Still, while the peculiar demonstrators left, a different kind of fear continues to linger in the parish, this one with a steady, everyday flavor.

On Oct. 8, pastor Fr. Raul Marquez spoke in his homily at the 9 a.m. English Mass about St. Paul's admonition to avoid anxiety as expressed in St. Paul's Letter to the Philippians.

Fr. Raul Marquez, during Mass at St. Peter Church (Peter Feuerherd)

The approximately 200 worshipers heard the priest counsel them to pray about anxious events pervading the headlines, including the Las Vegas shootings. Three hours later, the 800-seat church was nearly filled as Marquez spoke on ansiedad, the Spanish word for anxiety. The cause for this portion of his flock are Trump administration immigration policies. These days Marquez spends much of his time protecting his flock from threats that they are no longer welcome here.

"It's what I hear everyday," Marquez, himself an immigrant from Colombia, told NCR after Mass. "It is in the heart of everybody."

A woman in her 20s from nearby Gresham said her husband, born in Mexico and without documents, fears being expelled everyday when he goes to work. Others told NCR similar stories.

Dinorah Jimenez (Peter Feuerherd)

Marquez noted that families are being broken up, with a mother or father sent back to Mexico on a regular basis. Some of their children, including the 20-year-old Jimenez, who plans to study theology and wants to make a career of church work, are hanging on to the thread of the Deferred Action for Child Arrivals program, also known as DACA, that for now allows them to stay in the country. She came here when she was 2 years old.

Marquez hears the ansiedad regularly in his role as pastor. "Father, it's my last Sunday here," he will be told by parishioners facing deportation orders. Much of his time is spent writing letters to judges in support of his beleaguered parishioners. He goes to court on a regular basis and stands with those facing deportation. Sometimes, establishing an undocumented immigrant's place in a church community will help. Often it doesn't.

"We do a lot of tamale fundraisers," said Marquez, noting that the parish tries to defray the cost of immigration attorneys when it can.

Despite the immigration obstacles, if Steve Bannon, former White House chief strategist for the Trump administration, wanted proof for his controversial thesis aired on "60 Minutes" that the Catholic Church needs Latino immigrants, St. Peter would be a prime example.

St. Peter, once a parish in decline, took off when it was designated one of two parishes in Portland to offer Mass in Spanish back in the 1980s. Today there are more, but St. Peter remains a destination church for many Mexican-American Oregonians, who come here from all over Portland and its suburbs.

St. Peter Church in Portland, Oregon (Peter Feuerherd)

The parish retains an Anglo community. But that group has declined in numbers and is rising in age. Vietnamese and Filipinos who live in the neighborhood attend the English Mass. Marquez, 47, came to St. Peter Church five years ago, just two years after being ordained for the Archdiocese of Portland. He studied at Mount Angel Seminary in Oregon, but left his studies to help raise his deceased brother's family in Salt Lake City, only to return to priesthood preparation at an advanced age that doesn't show on his boyish face.

He came to St. Peter's intent on both promoting Latino ministry while also cementing bonds with the remaining Anglo parishioners. His easygoing manner, and fluency in Spanish, English and American culture, have worked to bring the parish closer together.

Before 9 a.m. Mass he strides towards the congregation, bantering easily with the parishioners. He tells them there is a reporter in the church today.

"Don't tell him the truth. Make me look good," he joked. He needn't have pushed so hard. While many Catholic parishes go through an "us vs. them" stage when Latinos arrive in large numbers, St. Peter appears to have emerged out of that phase. It's easy to hear praises to Marquez's pastoral skills from both Anglos and Latinos.

"It's a beautiful part of our church," noted long-term parishioner Mona Hansen, describing the Latino community at St. Peter. Her 45-year-old son, Patrick, sings in both the English and Spanish choirs. He is visually impaired and lacks short-term memory. Hansen describes her son as acutely aware of those who look down on him but has found acceptance in both choirs.

"If we didn't have a Spanish community, we wouldn't have a church," she said. "Our English Mass is small and getting older."

Advertisement

Mexican-Americans now do the bulk of the volunteer work, whether it be teaching catechism or providing the labor for parish fundraisers. Pastoral associate Arnulfo Delgado has supervised the installation of statues around the church popular with both communities in the year and a half he has served the parish.

"It used to be all I heard was 'us vs. them.' But I don't hear that anymore," said Hansen.

Marquez said his approach has been quiet yet intentional, focusing on the small items that symbolize unity. There are now combined fundraisers. The lectionary and altar server schedules have been combined. The staff is bilingual, ready to serve both English and Spanish-speaking parishioners. Parishioners now refer to the 9 a.m. Mass group and the noon group. Before, they were simply designated as Anglos and Latinos.

"I love that because you are not being defined by your race," he said.

Children attend religious education at St. Peter Church (Peter Feuerherd)

Religious education is now a combined enterprise held between both Sunday masses. The children taught are largely Mexican-American but the lessons are now in English, because the children are more comfortable learning in the language they hear in public school. The prayers, however, remain recited in Spanish, the language of the heart they learn at home.

Creating common schedules for altar servers provided a bonus. The older Anglo community likes to see young people, and the Mexican-American servers offer youth.

The young future of the church is Mexican-American. Jimenez represents that dynamic. She would like to serve the church, if her DACA status continues to allow her to work and stay in the country.

Amidst this ethnic mix, another element has been added. Marquez is now trilingual at Sunday Mass with the inclusion of a diocesan-wide liturgy for the deaf every Sunday. It is held in-between the English and Spanish Masses. Marquez learned this third language from a deaf seminarian classmate. Their full inclusion into the life of the parish is still a work in progress, noted Marquez, but St. Peter Church has a lot of practice and should be up to the challenge, he said.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and is a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]

We can send you an email every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email newsletter sign-up.