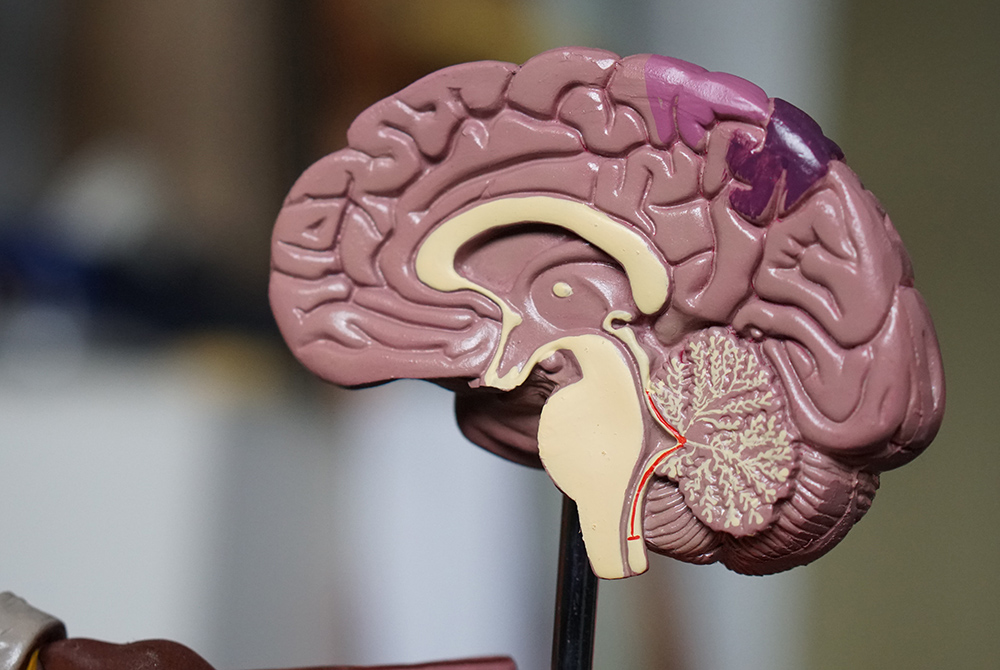

(Unsplash/Robina Weermeijer)

Some Catholic doctors and medical ethicists have raised concern about possible forthcoming changes to the legal definition of brain death used in most U.S. states. The issue of whether family consent should be required for brain death testing is of particular importance, especially since a determination of brain death can allow for patients' organs to be harvested if they are registered as an organ donor.

"It's somewhat interesting that the church formally declared a human person begins at the moment of conception, but at the end of life they're kind of passing the buck," said Joseph Eble, president of the Tulsa, Oklahoma guild of the Catholic Medical Association and co-author of a March article in Homiletic & Pastoral Review expressing concern about potential Uniform Determination of Death Act changes.

"Obviously, at the moment of conception, the human person doesn't have a brain, so you can't say that a brain is necessary to have a human person," he said, adding that the issue of brain death is complicated.

"My personal goal is for the U.S. bishops' conference and eventually the magisterium to clarify this issue for the sake of the faithful, because it's too complex for the average person," Eble said.

Last August, a study committee of doctors and ethicists assembled by the Uniform Law Commission began deliberating whether the commission should update the Uniform Determination of Death Act, or UDDA, which sets out two legal definitions of death, one by circulatory and respiratory criteria and the other by neurological criteria.

The Uniform Law Commission is a nonprofit association of lawyers, judges, law professors and legislators founded in 1892 that "provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law," according to its website. The Uniform Determination of Death Act, which has been adopted by most U.S. states, is one such piece of legislation drafted by the commission. If the commission decides to revise the text of the UDDA and state legislatures accepted those revisions, legal criteria and procedures for determining brain death could change across the country.

The law sets out criteria for doctors for declaring deaths of patients. In its current version, it states, "An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards."

Though some individual states that have adopted the UDDA have tweaked its language or have passed additional laws that dictate how doctors can determine death, the text of the UDDA has not been changed since it was first written in 1980. Now, after the Uniform Law Commission's internal discussions and debates have concluded, the group may recommend significant UDDA revisions.

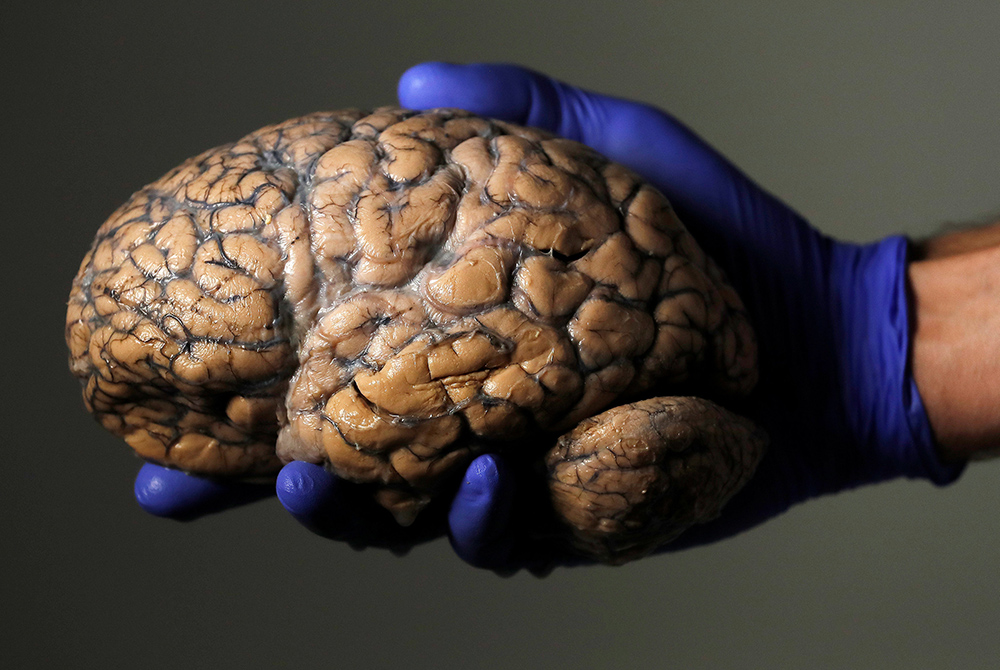

A Belgian researcher holds a human brain as part of a study into psychiatric diseases July 19, 2017. (CNS/Reuters/Yves Herman)

One potential change would be a specification that doctors need not obtain consent from patients' next of kin before performing brain death diagnostic testing, including the controversial apnea test, which involves removing a patient's breathing tube and allowing their carbon dioxide levels to rise to see whether they begin to breathe spontaneously. Most diagnostic tests used to determine brain death carry no potential risk to patients whatsoever, but the apnea test has the potential, at least theoretically, to cause total brain failure in a patient whose brain is still partly functional, said Dr. Allen Roberts, chair of the Clinical Ethics Committee at Georgetown University Hospital.

"The problem is that the apnea test specifies that the carbon dioxide level rise in the blood to a high enough level that the brain stem is maximally stimulated to generate a breath," said Roberts. "… The problem with that is that hypercapnia, or high carbon dioxide level, can cause swelling of the brain, and so if [the patient is] not brain dead when they start the apnea test, the brain may sufficiently swell to precipitate brain death."

However, Roberts added that he is not aware of any reports of this occurring.

A widely-read 2019 article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, titled "It's Time to Revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act," argues that the UDDA needs an update to address controversies and questions around brain death. In it, authors Ariane Lewis, Richard J. Bonnie and Thaddeus Pope suggest that the law should use a more specific definition of brain death, and that determinations of death should be made in accordance with any future updates to medical standards.

Lewis, Bonnie and Pope also propose that doctors should not have to obtain consent before evaluating patients for brain death. "Reasonable efforts should be made to notify a patient's legally authorized decision-maker before performing a determination of death by neurologic criteria, but consent is not required to initiate such an evaluation," they write.

Samuel Thumma, the Uniform Law Commission study committee's chair and a judge on the Arizona court of appeals, told NCR in an email that the Lewis, Bonnie and Pope article is among those that were provided to the committee for consideration.

"Issues being considered include lack of uniformity in medical standards used to determine death by neurologic criteria, the relevance of hormonal functions and whether notice should be provided before a determination of death," Thumma wrote.

Thumma also confirmed to NCR that the study committee is considering the issue of whether consent should be required before brain death diagnostic testing can be conducted.

Advertisement

Jason Eberl, a Catholic bioethicist and professor of health care ethics and philosophy at Jesuit-run St. Louis University, told NCR that church authorities may want to take a stand on the issue of requiring or not requiring consent to do the apnea test.

The apnea test is not therapeutic, Eberl said. Therefore, the principle of double effect, a doctrine of Catholic moral theology, does not necessarily apply to it.

"There's what's called the principle of double effect, which does allow us to do certain actions, even if there's a foreseen negative side effect, as long as the goals are proportionate [and] there's a proportionate value between the positives and the negative effects," Eberl said.

"Part of the issue here is that the apnea test is not for the patient's benefit," Eberl explained. "Typically when we use double effect, we're saying, 'Well, this is something good for the patient, that has a foreseen risk to the patient' … but in this case, you do the apnea test really to just assess whether the patient's alive or dead and whether you're going to continue ventilation, and/or whether you're going to procure the patient's organs for transplant."

Because of the close relationship between brain death diagnoses and organ donation, the Uniform Determination of Death Act is "a very touchy subject," Roberts said.

"The Uniform Determination of Death Act is a big deal because it has everything to do with organ procurement," he explained. "The act is protective of the public inasmuch as organs must not and legally cannot be procured from someone who is not declared dead by one or the other of the criteria set forth."

The church affirms organ donation and accepts the validity of brain death as a form of death in accordance with medical standards, Eberl said, but debate continues among Catholic doctors and ethicists about which specific neurological criteria ought to define brain death.