In January, Lindsey Faust and her partner visited the Loretto Motherhouse in Nerinx, Kentucky, for a mini vacation. Faust was a former volunteer with Loretto Volunteers and shared a rapport with the sisters and community members. It was almost like home to her. During their stay, Faust's partner, out of curiosity, inquired about the priest who lived there, celebrating daily Mass. It was then that a community member revealed details about Fr. J. Irvin Mouser that no volunteer knew.

Mouser, a priest from the Archdiocese of Louisville, was removed from public ministry in 2002 on charges of child sex abuse. He is accused of abusing five boys during his time as a priest at the parishes of St. Helen in Barren County and St. Francis of Assisi in Jefferson County. The Holy See directed Mouser to live a life of "prayer and penance" — he was not to serve in any active ministry as priest, celebrate Mass publicly or don clerical garb.

But Mouser did all of that while living in Loretto, where he served as chaplain to the Sisters of Loretto. There he was also in close proximity to children, since students from a nearby high school and young children would often visit the motherhouse and the adjoining farm.

When lawsuits alleging sexual assault were filed against Mouser, then-Archbishop Thomas Kelly of Louisville (who died in 2011), sent Mouser to live in a private residence on the property of the Loretto Motherhouse. The archdiocese confirms that he was explicitly directed not to serve in active ministry. But at the request of the sisters, Mouser began offering Mass to them privately. The archdiocese is now led by Archbishop Joseph Kurtz.

"After a special request from the Sisters of Loretto, Archbishop Kelly permitted Father Mouser to provide private and restricted ministry to the Sisters, primarily in the infirmary. The Holy See approved this exception. Father Mouser was never appointed as the chaplain for the Sisters of Loretto," said Brian B. Reynolds, chancellor of the archdiocese, in a statement.

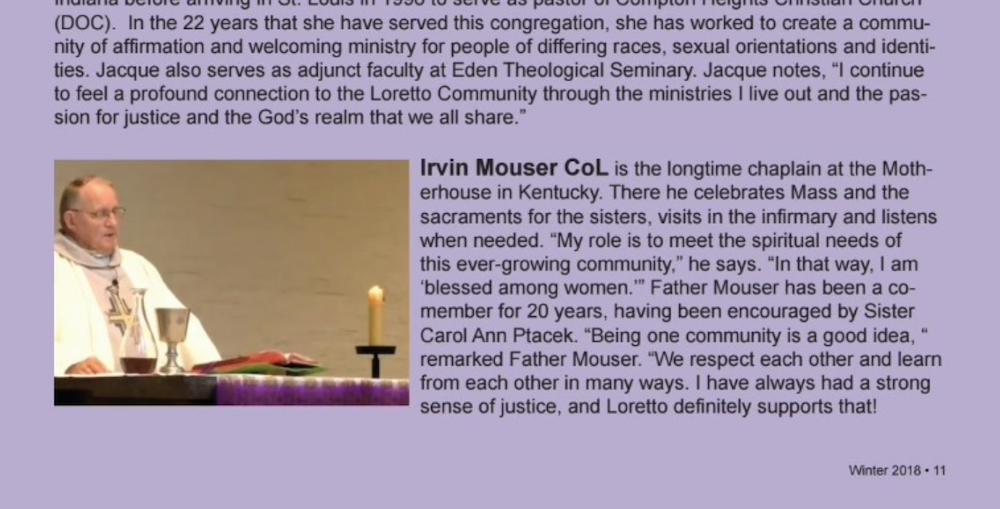

Despite these claims, Loretto identified Mouser as their chaplain in newsletters and magazines. With time, Mouser became an integral part of the community, and over the years, his participation grew. He was featured in photos on the community's website and their annual reports.

Reynolds said the archdiocese was unaware of the priest's expanded role.

Prior to moving permanently to the Loretto Motherhouse, Mouser was appointed as chaplain by the archdiocese twice — May 1993 to July 1996 and July 1996 to May 2002.

According to documents obtained by NCR, Kelly was aware of allegations against Mouser before the appointment in 2002. In 1992, Kelly had received credible proof that Mouser was an abuser.

Screenshot of Page 11 of the Loretto Magazine, Winter 2018 issue, under title "Ordained Co-Members enrich Loretto through their ministries"

The accusations against Mouser date back to the late 1960s and early '70s.

According to five lawsuits, Mouser abused four victims between 1968 to 1972 at St. Helen's parish and the fifth while he was at St. Francis of Assisi in 1974. The abuse occurred at various locations around the two parishes. According to one lawsuit, Mouser "forcibly sexually molested, abused, battered and assaulted" a victim at St. Helen's in 1968. Others allege forced oral sex, groping and fondling, among other charges. Victims also reported receiving gifts of clothes and shoes in return for sexual favors.

In 2002, after Kelly appointed Mouser to Loretto, a victim wrote to Kelly expressing his displeasure with the appointment, documents reveal.

"The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, ordered Mouser to live a life of prayer and penance. And it's the archdiocese's responsibility to make sure that happens. He was not supposed to be in ministry, he was not supposed to be wearing clerical garb. So, I believe, it's the archdiocese's failure here," said Terence McKiernan, co-founder of BishopAccountability.org, a group which monitors documents related to the sex abuse crisis in the church.

Faust, the Loretto volunteer, was "shocked, surprised and frustrated," when she learned about Mouser. "Loretto positions itself as being very progressive, very forward minded, and in a lot of ways it really is. It was shocking to me that he [Mouser] lived there. It was even more shocking that nobody, at least the volunteers, knew about it," she said.

She passed on the information to her volunteer friend, Adele McKiernan, a second-year Loretto volunteer in St. Louis, and daughter of Terance McKiernan. Adele McKiernan would visit the motherhouse for retreats, and during that time, volunteers were encouraged to sit and mingle with community members during meals, including Mouser.

Mouser also interacted with volunteers while preparing for Sunday Mass. "I mostly feel angry and misled by people who I see as mentors within the Loretto community," Adele McKiernan said.

Adele McKiernan began to dig deeper into Mouser's history and decided to speak up about the discomfort with his presence at Loretto. McKiernan wrote to the Loretto Executive Committee and volunteer program staff. In response to McKiernan's letter, Sr. Barbara Nicholas, president of the Loretto Community, said Mouser had been complying with restrictions. "My own faith requires me to be merciful, to stop judging, to stop condemning, to forgive," Nicholas wrote to McKiernan.

Advertisement

Transparency issues

Madeline "Maddy" Harries worked at the Nernix Hall High School in campus ministry. She often accompanied students to the motherhouse. When she got to know of Mouser, she admits feeling "sick to her stomach."

"I had students there! I was upset with the people I trusted," she said. Harries said that the sisters kept information on Mouser secret from volunteers accompanying children.

Eileen Harrington, Loretto's director of communications, and Reynolds said that Mouser had a campus supervisor and an external supervisor from the archdiocese who checked in with him periodically. However, they failed to inform the school about Mouser's history. When senior volunteers informed Nernix leadership, the school responded immediately by sending out an email to current and former students, parents and faculty members.

"As we continue to learn more, we will make a decision on the trips in the future, with student safety being the number one priority," read the statement.

Loretto told NCR that Mouser is no longer living in the community.

"Looking back, with the knowledge and understanding that we have today, we would doubtless make different decisions," said Harrington.

Harrington said Mouser lived in plain view of many. "He was always accompanied when he visited those who were informed. To Loretto's knowledge, there have been no allegations about him during the years he resided at Loretto," she said.

Terence McKiernan, who is Adele's father, raised doubts over the internal monitoring systems. "The danger, as revealed in this case, is that a relationship is developed with the accused priests. The Loretto sisters had a relationship for decades with him [Mouser]. And in such a situation, monitoring cannot be done correctly," he said.

McKiernan says supervisors need to approach this more like probation officers and not in a "naïve and trusting way".

Volunteers who spoke to NCR expressed disappointment with the Loretto community and the archdiocese.

Leora Mosman, a second-year volunteer, said, "I respected Loretto for the way they tried to deconstruct patriarchy and try to bring voice that were left out of faith-based institutions." But now she said she feels anger and confusion.

"It's horrible to learn that a perpetrator of sexual violence, who was so publicly known, was brought to live there. A majority of people in Loretto knew, so this was a well-informed choice they made," she said.

Kiara Quintanar, a volunteer since August 2019, identifies as "culturally Catholic," but finds herself disillusioned by the church. "I'm really feeling the need to actually distance myself from Catholic institutions," she said.

Quintanar said the volunteers had a mid-year retreat immediately after Mouser's history became public. The matter was discussed in the group, but she was disillusioned by the response she received from the leadership, who talked about mercy and forgiveness.

For Faust, Loretto was always a "genuine community." She questioned Loretto's decision to keep Mouser in the community. And for that, she blames the bishops. "I don't think they [Loretto] handled it well. But the archdiocese was not operating with accountability in mind," she said.

Harrington reiterated Loretto's commitment to social justice, saying their understanding of sex abuse and its effects on victims has grown and deepened over the years. "We want the Loretto Motherhouse to be a safe space for all. As has been our practice for years, all employees working at the Loretto Motherhouse have criminal background checks."