Bonnie McCoy is pictured in her permanent supportive housing unit in Southeast Portland on a recent afternoon. The 56-year-old, who has had four surgeries in two years, lost her housing after a divorce. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

Editor's note: This is the second in a two-part series on chronic homelessness and permanent supportive housing. The first part looks at the history and success of the housing model and is available here.

For years, Eve was a self-employed seamstress in Oregon, creating costumes for dancers, weightlifters and figure skaters and for the occasional Nativity reenactment. She rented a small house and made ends meet.

Then came the 2008 recession, the bank took over the house, "and they threw us out," said Eve, who asked NCR not to use her full name. "The first night I hit the street for real, it was cold and I didn't have a sleeping bag."

She tried to piece together places to stay, including motels before they got too expensive. "I'd go to 24-hour restaurants and order coffee, sleep on a train or take a nap on the bus," said Eve, now 72.

Homelessness and lack of dental insurance left her teeth in such bad shape they all needed to be removed, and she had several bouts of pneumonia.

"I coughed up blood," Eve recalled.

Between 2016 and 2022, chronic homelessness increased nearly 65% in the United States, with more people like Eve spending long stretches on the streets or in shelters. Advocates and homelessness experts say a critical part of the solution has existed for years, though it faces a number of challenges.

Bonnie McCoy shows an old photo of her three boys in her apartment complex in Southeast Portland. (NCR photo/Katie Collins Scott)

Permanent supportive housing, a combination of subsidized housing and support services, often onsite, is not just the most effective way to reduce chronic homelessness "but also the most cost-effective way in the long run," said Pascale Leone, executive director of the Supportive Housing Network of New York.

Catholic Charities USA launched a pilot in 2020 that aims to reduce chronic homelessness in five cities over a five-year period by, among other strategies, securing permanent supportive housing for those who need it. The initiative includes partnering with local, primarily Catholic, health care providers.

"I know people who've said to homeless people, 'Just get a job,' " said Eve. "But I know people working at McDonald's who are sleeping in their cars. I know people working at gas stations who can't get into housing."

Some on the streets can't give up a drug addiction, Eve added. "I also know there are a lot of people who don't start off with a drug addiction but end up with it because they are in a hopeless situation."

Mental illness and substance abuse disorder can impact an individual's housing status, but Gregg Colburn, a professor at the University of Washington, and data scientist Clayton Page Aldern use statistical analysis of existing data to show in their 2022 book, Homelessness is a Housing Problem, that the homelessness crisis in cities cannot be attributed to disproportionate levels of drug use, mental illness or even poverty. Instead, it is driven by housing costs and availability. The Pew Charitable Trusts likewise reports that a large body of research shows homelessness is driven by housing costs.

In recent years demand for housing rose while supply of new units plummeted, causing prices to skyrocket across the country. Meanwhile wages haven't kept pace with housing cost increases.

Kerry Alys Robinson, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA (Courtesy of Catholic Charities USA)

The severe shortage of affordable housing in the United States "is a moral crisis in urgent need of solutions," Kerry Alys Robinson, president and CEO of Catholic Charities USA, told NCR. "Housing is a basic human right, and our country should be a place where every individual and family has somewhere safe to sleep at night and a place they can call home."

The Healthy Housing Initiative

The goal of the Catholic Charities USA Healthy Housing Initiative — concluding at the end of next year but which organizers hope will be replicated — is to house a total of 698 chronically homeless individuals, reflecting a 20% decrease in each city based on 2019 numbers, and partner with local Catholic health care providers to reduce emergency room and hospital readmissions for the newly housed by 25% and connect 35% of the housed individuals with primary care and behavioral health services.

Someone is typically considered chronically homeless if they've experienced long-term homelessness and have a documented disability, including addiction or mental illness.

There is frequently an overlap between the chronically homeless individuals served by Catholic Charities agencies and the chronic patients admitted to ERs and hospitals, "so it makes sense we tackle these issues together," said Robert McCann, president and CEO of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington. The Spokane-based nonprofit participated in the pilot along with counterparts in Las Vegas, Detroit, St. Louis and Portland, and their respective dioceses supported the effort.

According to a report shared with NCR, approximately 500 chronically homeless people, or nearly 72% of Catholic Charities' goal, have been housed so far. Delaware State University recently began an evaluation of the pilot, and Curtis Johnson, vice president of housing strategy for Catholic Charities USA, said the results will likely be published in early 2025.

Curtis Johnson, vice president of housing strategy for Catholic Charities USA (Courtesy of Catholic Charities USA)

"Catholic Charities is right in the middle of this issue of chronic homelessness and has been for a long time," said Steve Berg, chief policy officer for the National Alliance to End Homelessness. "They aren't afraid to take it on as an issue and really work to find the best way to approach it."

Johnson said the pilot cities have successfully addressed housing in diverse ways, with not all building new units.

Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington has been a major housing producer, "while St. Louis folks have said — we work with local landlords and find existing properties for our residents because we know how long the development process can take," he said.

The Spokane-based Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington already had served as a model for others wanting to tackle supportive housing projects. Two decades ago, there were nine affordable housing complexes in eastern Washington; now there are 67, reflecting 1,600 permanent supportive housing units.

"I'm hoping by the time I retire I see a landscape where most of the 160 or so local Catholic Charities in this country are actively involved in building housing in this kind of fashion," said McCann.

There are studies that indicate permanent supportive housing can improve mental and physical health, but the Catholic Charities initiative attempts to boost the level of medical services residents can access and their overall health outcomes.

Gonzaga Family Haven, an affordable housing complex built by Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington, opened in 2021 and includes 73 units of permanent supportive housing. (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington)

Chronically homeless individuals frequently are "the most medically fragile, most ill people in a community who aren't already in a hospital or in some form of assisted living," McCann said.

It is no surprise that homeless people have higher rates of hospital and ER use than the general population, and "unless you help solve their medical issues, it's going to be a lot harder to stay in that housing," said McCann.

The pilot's success so far includes a 57% drop in ER visits for the 17 homeless individuals housed by Detroit-based Catholic Charities of Southeast Michigan, which partnered with Ascension Healthcare.

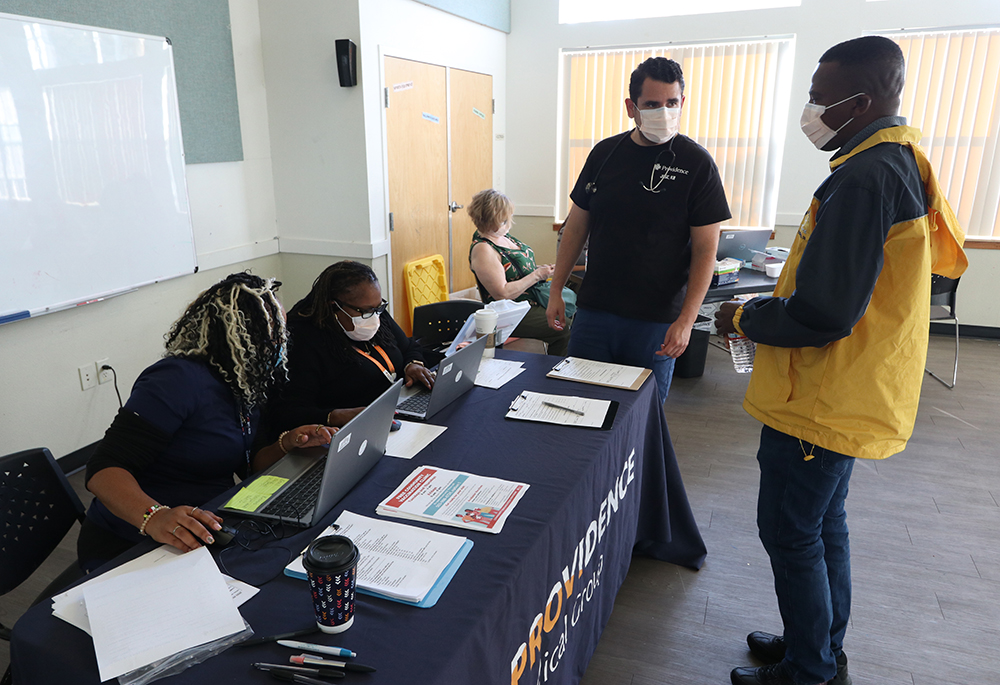

In Oregon, Providence Health & Services has held health fairs at Catholic Charities' affordable housing locations.

There is a "huge medical value" to the fairs but "also a real behavioral health benefit that addresses the social isolation many people have felt," said Rachel Smith, senior program manager with Providence.

She recalled one fair where an individual learned they had diabetes and very high glucose levels.

"It was getting to a point where it was dangerous for them, but we were able to catch that in a place where they felt safe and comfortable," Smith said. "They were able to come down to the community room, and they had friends around that could offer support. It was powerful."

Kamica Armenta, Teresa Johnson and nurse Jose Zaragoza, all from Providence Medical Group, tend to a patient during a health fair this fall at Kateri Park, an affordable housing community operated by Catholic Charities of Oregon. The health fair was a result of Catholic Charities USA's Healthy Housing Initiative. (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Oregon)

Imperfect but 'a godsend'

Although decades of research show coupling housing with services is an effective way to care for people who are chronically homeless, a range of difficulties constrain more widespread, successful permanent supportive housing projects.

There needs to be more permanent supportive housing and "more money from any source would be good," said Berg, noting the model has been funded by everything from private donations to hospital revenues. "But the only source capable of getting to the scale that's needed is the federal government."

Homelessness advocates often point to the reduction in chronically homeless veterans as an example of what could be possible with a heftier financial commitment from the federal government. Its investment in permanent supportive housing for vets meant New York City virtually eliminated chronic homelessness among the group, and since 2010 the homeless U.S. veteran population fell by 55%.

Leone said that despite studies affirming supportive housing does not increase local crime or reduce property values, NIMBYism continues to be a big challenge, and it can add on years to projects.

Turnover and staffing also plague supportive housing due to low pay, burnout, lack of adequate training for difficult work, and excessive caseloads, according to experts, and there are very long wait times for units — it can take up to five years for such housing in Portland.

At the same time, some advocates believe there are glitches around who gets prioritized.

Rose Bak, chief program officer at Catholic Charities of Oregon (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Oregon)

For most permanent supportive housing, communities are required to use what's called coordinated entry, through which people with the most urgent needs are given housing priority.

Rose Bak, chief program officer at Catholic Charities of Oregon, said individuals who engage most with public services and health care systems tend to score higher on the list, and those who engage less — transgender individuals, women and homeless youths, for example — don't score as well.

"There are self-identified women who we've known a long time, who have been homeless a long time and that have a lot of vulnerability, but they don't score high on that list because they haven't been arrested a lot, haven't been to the hospital much," said Bak.

She added there are some efforts underway nationally to address "what can be a skewed system."

Securing funds for the supportive services is one of the biggest challenges, according to advocates.

"You can get bricks-and-mortar money from tax credits and money to pay the rent from Section 8 vouchers, but to get the money to pay for services, you've got to go pound the pavement," said McCann.

Johnson said an objective of the Catholic Charities USA pilot is to track any cost savings to health systems or to insurers that could then "be leveraged to encourage investment in affordable housing and help fund those supportive services."

"Paying for affordable housing is like quilt making," he said. "You get a bit from here and another from there, and then you build the thing."

Kateri Park is a Catholic Charities of Oregon affordable housing complex in Southeast Portland that includes 20 permanent supportive housing units. Part of dealing with NIMBYism is to "run efficient, well-managed and beautiful spaces," said Curtis Johnson, vice president of housing strategy for Catholic Charities USA. Catholic Charities agencies' budgets "are not huge, but we want residents to be proud to live there." (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Oregon)

Due to Medicaid expansion, more states can use Medicaid funds to cover primary, behavioral and mental health services. (An experiment within the Medicaid program enables some states to use Medicaid funds for rent and utilities, something Catholic Charities USA and its member agencies have advocated for.)

But properly billing Medicaid to get reimbursed for services is complicated, and nonprofit staff don't always know how to do it.

Leone said she believes permanent supportive housing ultimately is a cost-effective investment for communities because "it is cheaper to fund supportive housing up front, and to get people in it quickly, than it is to let them languish in shelters, jails and prison or on the street."

She pointed out that Los Angeles saved 20% overall after launching a permanent supportive housing program for nearly 1,000 individuals.

Advertisement

In 2020, California researchers shared results from a randomized trial of chronically homeless people in Santa Clara County. They found that individuals in permanent supportive housing had fewer psychiatric emergency room visits and shelter use, "which also reduces costs," said Leone.

But she added that anti-development sentiment from both the political left and the right makes it "very challenging" to build and maintain permanent supportive housing at the scale that is needed.

Marisa Zapata is director of the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative and a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. She emphasizes cost shouldn't be an excuse not to build more housing. She thinks it would be better if people would "accept that public housing happens at a significant loss, that it's not always going to pencil out."

Marisa Zapata is director of the Homelessness Research and Action Collaborative and a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. "Permanent supportive housing is the most evidenced-based solution to chronic homelessness that exists," she said. (Courtesy of Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative)

An additional obstacle for supportive housing is tied to attacks on the "housing first" approach. Housing first supports people being housed without preconditions or barriers such as sobriety or treatment. It stresses the need for services, but it's not a specific program like permanent supportive housing. Many supportive housing programs, however, operate under the philosophy.

Critics say housing first ignores people's underlying issues, is ineffective and funds should go toward programs that require employment or sobriety.

A conservative think tank in Texas called the Cicero Institute says on its website that "permanent supportive housing doesn't address homelessness — it creates demand for more homelessness and supports cronyism."

The organization created model legislation, and at least a half-dozen states have introduced or passed bills based on the template. Missouri was the first to pass a bill that included language preventing state and federal funds for homelessness to be used on permanent supportive housing.

Robert McCann, president and CEO of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington (Courtesy of Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington)

McCann said some people will argue that chronic homelessness had gone up recently because of the federal housing first policy. "That's simply not true," he said. "It's no more true than to say the reason there are more cases of childhood cancer is because this country built more children's hospitals."

He cited the high prices and low inventory of housing as among the true primary drivers of the increase.

"When you are trying to do day-to-day survival, you are not going to be able to address something like a behavioral health issue," said McCann. "It is not something even discussable until you get to a stable place, to stable housing."

Zapata acknowledged there are communities having a hard time implementing permanent supportive housing and housing first as they were intended.

"But studies show they are still better than the alternatives, like shelters or living outside or mandated service requirements," she said.

Before Thanksgiving, Eve moved into her new home, a one-bedroom apartment in permanent supportive housing, as part of Catholic Charities USA's initiative.

She now has a car and said she tries to aid others experiencing homelessness when she can, regularly driving people to various Portland charities for food or services.

With the stability of permanent housing, she was able to recently have surgery to care for her severe dental issues. She hoped to be fully recovered well before Christmas.

"Catholic Charities has helped me in every way possible, especially when I've been particularly down," said Eve. "They are a godsend."

[This article was made possible by a grant from the Hilton Foundation.]