Rabbi Arnold E. Resnicoff, retired Navy chaplain, stands next to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. (NCR photo/Rick Reinhard)

Back in an era when the term "terrorism" still held the power to jolt, Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff came face-to-face with its raw reality in the aftermath of a truck bombing of Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon.

A naval officer and chaplain to the U.S. Sixth Fleet at the time, Resnicoff had arrived in the city on a Friday, Oct. 21, 1983, to lead a memorial service for a Jewish Marine who had been killed by a sniper. As an observant Jew, he didn't travel because of the Sabbath and consequently was nearby the morning of Sunday, Oct. 23, when the bomb killed 241 American military and injured scores more. The dead included 220 Marines, the Corps' worst loss since the assault on Iwo Jima in 1945.

Among the first to arrive at the site of the bombing, Resnicoff and others "faced a scene almost too horrible to describe," he wrote that evening. "Bodies and pieces of bodies were everywhere. Screams of those injured or trapped were barely audible at first as our minds struggled to grapple with the reality before us — a massive four-story building, reduced to a pile of rubble; dust mixing with smoke and fire, obscuring our view of the little that was left."

His report — in many ways an extended theological reflection — received wide coverage the following April when President Ronald Reagan read it for a speech to the 1984 "Baptist Fundamentalism" convention organized by Rev. Jerry Falwell.

That the thoughts of a rabbi would be read by a nominally religious president to a gathering of Christian fundamentalists was not the only episode in Resnicoff's life with a counterintuitive twist and a brush with influencing history. He was the first chaplain to teach a course at the Naval War College and helped create the college's annual conference on ethics and the military.

In extended interviews with NCR near his home in Washington, D.C., Resnicoff, 71, discussed his career as a naval officer and chaplain and how it has affected his view of religion, of warfare and its effects, of LGBT rights, and of military ethics on and off the battlefield.

Early formation

As a teenager, Resnicoff had his sights set on an acting career. He went to Dartmouth College as a drama major, but the weight of a family obligation pulled him in a different direction. His grandfather, an Orthodox rabbi, escaped from Russia in 1903 when Resnicoff's father was just three. Arnie, as he refers to himself, grew up in a "super patriotic family" and as the eldest of three boys, was expected to "pay my dues and serve." So instead of heading to New York and a possible stage career, he went from Navy ROTC straight to the rivers of the Mekong Delta in South Vietnam.

Arnold Resnicoff at the 1998 White House Breakfast for Religious Leaders, hosted by President Bill Clinton (Provided photo)

Shortly after arrival in August 1969, an Episcopal priest who made regular rounds to the boats in that region approached the young Resnicoff.

"He came up to me and said, 'You're Ensign Resnicoff,' and I said, 'Yes, sir.'

"He said, 'You're Jewish,' and I said, 'Yes, sir.'

"He said, 'You've just volunteered to be the Jewish lay leader for the Mekong Delta.' "

Out of that introduction grew a friendship. One of the first things the Episcopal priest told the new lay leader was, "You have to want to be a better Jew." That led to suggestions for books to read, which Resnicoff had friends send from home.

"So it was this Episcopal priest who first planted the seed in my mind to be a rabbi. I always tell people I learned a lot from him about what it means to be a person of faith, to be a chaplain. I also learned what the word 'volunteer' meant in the military."

Advertisement

Resnicoff completed his year in Vietnam and two years in naval intelligence in Europe and then moved on to become a rabbi.

He agreed in 1976 to a three-year term as a Navy chaplain because he knew there was a shortage of rabbis in the chaplaincy. Nearly 25 years later, he retired.

Humanity amid war

"There was a sense of God's presence that day in the small miracles of life which we encountered in each body that, despite all odds, still had a breath within," Reagan read from Resnicoff's reflection before the audience of fundamentalists. "But there was more of His presence, more to keep our faith alive, in the heroism and in the humanity in the men who responded to the cries for help."

Arnold Resnicoff wearing a piece of fellow chaplain Fr. George Pucciarelli's cap as a kippa, Beruit, Lebanon, 1983 (Provided photo)

His fellow chaplain, Fr. George "Pooch" Pucciarelli, a Catholic priest, "cut a circle out of his cap — a piece of camouflaged cloth that would become my temporary head covering.

"Somehow, we wanted these Marines to know not just that we were chaplains but that he was a Christian and I was Jewish," he had written. "Somehow, we both wanted to shout the message in a land where people were killing each other — at least partially based on the differences in religion among them — that we, we Americans still believed that we could be proud of our particular religions and yet work side-by-side when the time came to help others, to comfort and to ease pain."

Paradoxical as it might seem, the search for humanity amid the roar and chaos of war became a measure of religious influence for the rabbi, or perhaps a sign that one could make the transition back to peace. The paradox was unwittingly highlighted during Reagan's reading when a group of protesters began chanting "Bread not bombs!" and other anti-war slogans during the speech.

Reagan deftly handled the interruption, which was brief, and the protesters were escorted out. But Resnicoff doesn't brush off the question that arises out of that event. Do the protesters have any legitimacy?

The example of humanity and heroism he conveys in his written statement resulted from extreme circumstances. But had he and other chaplains ever considered the question of whether it was necessary or even right to place soldiers in such circumstances?

"That's a very difficult question," he said in the interview. "I would say a lot of times — and this is not a very highfalutin metaphor — my understanding of Judaism can't answer some questions as to why you're dealt the hand you're dealt. The question is: How do you play the cards?"

"Where you are, if there is no humanity, you be humanity, you be the force for good. I think that is at the heart of so much that I believe and which I try to teach."

—Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff

Speaking of that awful day in Beirut, he said, "I think one of the choices you have in a situation like that is to say there is no God; how can there be a God in a world like this? Or hold on and keep faith and say, 'This is a hand of God somehow because these people are not giving up. This person is risking his life or her life, this person is crying, knows all the terrors in the world, is crying over the body of somebody maybe he loved, maybe he didn't even know.' Are we going to become numb to that, are we going to give up and say nothing ever counts?"

He relates that experience to less dramatic events — everyday human loss and suffering. "You have a choice," he said, "of saying, 'There's no God, I don't believe — or I will believe, I will believe, I will believe.' "

In answer to the earlier question about whether military decisions can be questioned, he said, "We allow for conscientious objection, but not for selective conscientious objection." In the United States, conscientious objector status is granted only if the individual objects to all violence; one can't obtain such status by objecting to a particular war.

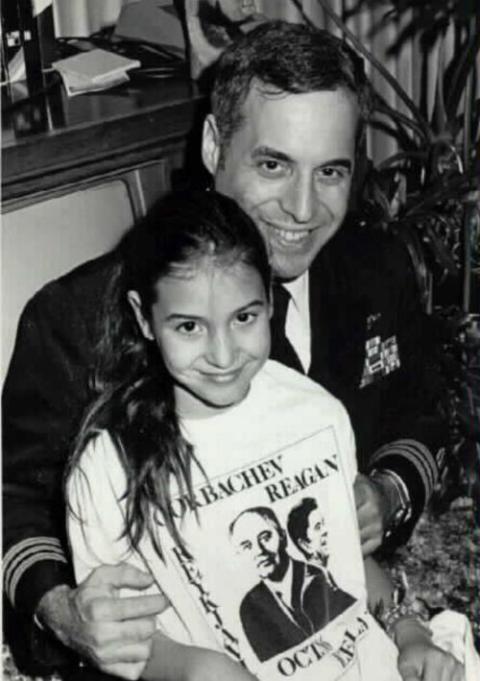

Arnold Resnicoff with his daughter in 1986 at home (Provided photo)

The discussion leads to the core of Resnicoff's thinking about good and evil in the conduct of war. He has encountered members of the military who had begun to question the efficacy of a particular war or action "based on what they saw, and they started to question everything, and they decided that violence was never the answer. It just didn't matter that this evil could exist.

"The ultimate question of war, as far as I am concerned, is: How much bad can you do for the sake of good?" He believes that the reason the U.S. withdrew from Vietnam, for example, was because the scale tipped in the direction of too much bad for too little good.

If someone came to him who had "absolutely reached the conclusion that he or she couldn't be part of violence in any way, I would help them apply to be a conscientious objector." If, on the other hand, someone would say they understood that sometimes violence is necessary — "I would defend my life, I would defend my wife, I would defend my children, I would defend my country, I just don't think this war is the right war" — that would trigger a different conversation.

"I would say to them in every place you are you can add to the humanity of your unit, you can add to the humanity of your team. You cannot get out of the military based on that, although you can try. But we would have a very serious conversation."

As for the protesters' chant, he said: "I wish it was so simple that we had a choice of feeding more people or fighting more."

At the same time, he said, "I would think that we need protesters, we need people who are against the war and, ultimately, if our military is the right military, nobody would be more against fighting than the military. The people who have seen their own people blown apart — we should be the most anti-war. We should be the ones who pray the most that we would be out of a job someday. So saying 'bread not bombs,' God bless the people who believe that. I personally don't think it's a simple choice."

'It's not triumphal'

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is singular among war memorials in the nation's capital. It appears as a simple sweep of highly polished black granite and was designed to resemble, from on high, a gash in the Earth's surface. What is most impressive, perhaps overwhelming, as one proceeds from either end and sinks, panel by panel, deeper into the thousands upon thousands of names of the war dead carved into its surface, is the awareness that grows of the extreme cost a war can exact in human loss.

Arnold Resnicoff speaks during a National Days of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust ceremony aboard the USS Puget Sound, the Sixth Fleet's flagship, while in port at Malaga, Spain in 1984. (Provided photo)

"When Jan Scruggs, a former Army corporal, had the vision to create the veterans' memorial, he started looking for people to be part of the group," said Resnicoff, "and one of the things they looked for were chaplains to give the prayers at the dedication." When they discovered Resnicoff — not only a chaplain but someone who had been a line officer in Vietnam — "they grabbed me. So I became part of that group working toward that memorial."

Resnicoff had no influence on the design but said he likes that the monument was not dedicated to a war but to those who died fighting.

"I call it America's version of the Kotel of the Western Wall in Israel. It's holy ground. People go there — they lift up babies to touch a name, and you wonder if that's a grandfather or a great-uncle. They leave things, just like people leave prayers and notes at the Kotel."

At the wall's formal dedication in November 1982 (marking the 35th anniversary), he delivered the closing prayer.

"It's not triumphal, and that's the point, " he said. "The idea that this makes no statement on the war, but says no matter what you think of the war, come together to honor our dead — that was the brilliance of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial."

Healing other divisions

Resnicoff was instrumental in another effort to heal divisions. He offered prayers at the repeal of the military's "don't ask, don't tell" policy regarding homosexual people in the service. It was a fitting role for someone who had worked on the issue for years, an extraordinary role for both a conservative Jew and a military officer.

From left: Arnold Resnicoff; Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne; Resnicoff's mother, Blanche Resnicoff; and Resnicoff's daughter, Malka Zeefe at an award ceremony in 2006 where Arnold Resnicoff was presented with the U.S. Air Force Decoration for Exceptional Civilian Service, the highest award that can be given to a civilian (Provided photo)

"I was very much against 'don't ask, don't tell' because I thought it was an immoral policy that forced people to hide who they were at the same time we were promoting core values that included honesty," he said.

It was a point of view that originated in a personal story. His younger brother, Joel, was gay and an early victim of the AIDS epidemic. He died in 1986 at age 38. Resnicoff remembers his mother's care for his younger brother at the hospital, where, he said, she became a kind of surrogate mother for other AIDS patients whose families had abandoned them.

"Maybe that gave me a little extra courage. When I spoke out, I would think of him looking down at me from heaven, hoping he would be proud of me."

He spoke out in several circumstances, once in response to the public intimidation and mocking of a woman, a former Army officer who was head of an organization of gay veterans, who was on a panel at the Naval War College discussing the issue of gays in the military. During the presentation, he said, she was greeted with boos and ugly, defamatory language. He said he finally stood and said that that was no way to treat a guest speaker. "I really wouldn't want to sound holier than thou, but we should listen. It's not a wrestling match."

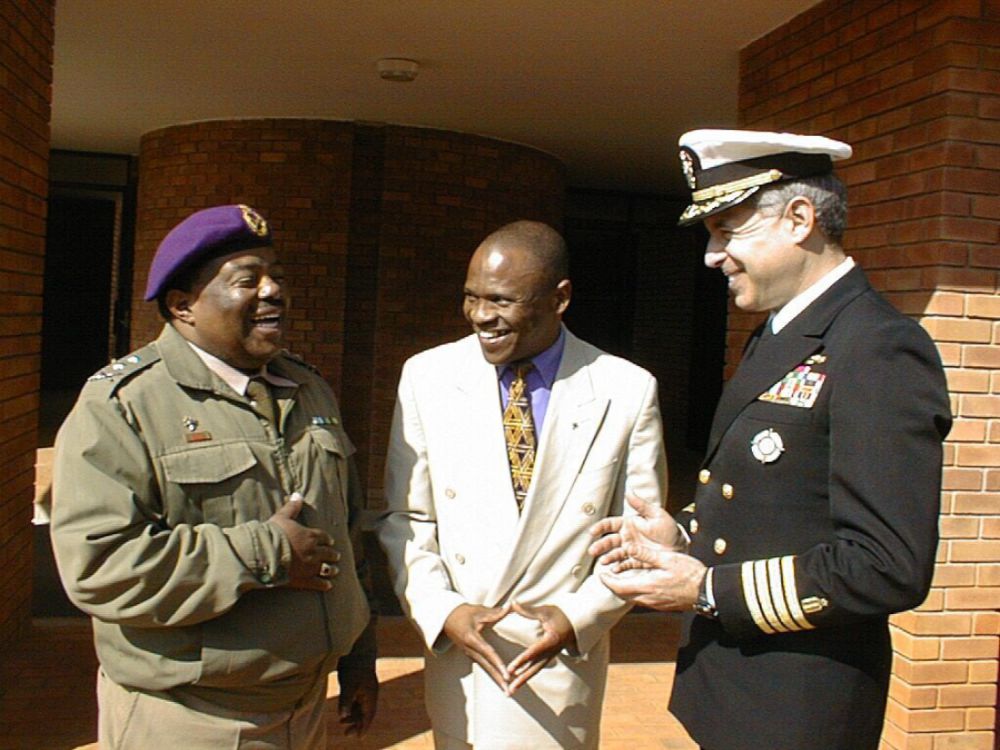

From left: Major General Fiume Gqiba, Chief of Chaplains for South Africa; Rev. Sabelo Maseko, the Chief of Chaplains for Swaziland; and Arnold Resnicoff, U.S. Navy officer and chaplain, in 1999 in Swaziland (Provided photo)

It didn't make him popular with others; in fact, he said, things got rather antagonistic. But he returned regularly on invitation to speak at the war college on ethics and often included a segment on accepting gays. "Those of you who are heterosexual, think of how you would feel if someone told you it is no longer legal to be heterosexual, that you have to be homosexual," he asked. "And people literally told me they had never thought of it that way."

He was asked to say the prayer at the ceremony during which President Barack Obama signed the repeal of "don't ask, don't tell."

Protection from being overtaken by rage

Two other areas in which Resnicoff was particularly active was promoting the use of chaplains in efforts of reconciliation and peacemaking and advocating for "spiritual force protection."

From 1997 to 2000, he served as a principal advisor to Gen. Wesley Clark, head of the U.S. European Command, on matters of religion, ethics and morals. It was during that period that he realized that chaplains were able to connect with religious leaders and groups in ways not available to other officers and to bring groups together in efforts to bridge ethnic and religious divides.

He thought it "foolish" to "throw in an intelligence officer" and say, "Learn the differences and come tell us about them." Instead, he urged that "the committees or groups of people that we have interface with the leaders of the country should include a chaplain, and that chaplain should get to know the NGOs [non-governmental organizations] and the religious groups, and we can fill you in more on the religious differences and what's important."

The people who have seen their own people blown apart — we should be the most anti-war. We should be the ones who pray the most that we would be out of a job someday. So saying 'bread not bombs,' God bless the people who believe that. I personally don't think it's a simple choice."

—Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff

The idea occurred to him during the wars in Kosovo and Bosnia. He eventually brought a contingent representing the various religious groups in Bosnia to the United States and met with religious groups here "just to instill the idea that you could work across religious lines. Because my opinion was if religion could be at the heart of war it also could be at the heart of reconciliation and ending war."

During that same period, the term "force protection" was ascendant in military circles. "We needed to protect our troops, protect our troops, protect our troops. And it got to the point where protecting the troops almost became more important than the mission," he said. "So I introduced this idea that we don't just want our troops to come back physically whole, but as close as possible to the human beings they were when they went in." He began to advocate for "spiritual force protection."

He said he wrote papers claiming that "war was a danger not just to human beings, but to humanity. Unless we prepared for this spiritual danger, it could bring out the animal within us," he said.

Resnicoff believes "we have to distinguish between outrage and rage. We don't want to become so numb that we don't feel horror at things that go on in war. We don't ever want to lose that outrage." At the same time, he said, the person has to be protected from being overtaken by rage.

He advanced the ideas in writing and in presentations to military commanders in Europe, giving a number of speeches on the concept at various levels and to chaplains. He thinks it slowly began to have an effect.

While much has been done and written since the late 1980s on the subject of "moral wounding," and the transition from war to peace — an area of work in which Resnicoff thinks the military should be investing more heavily — he also thinks "spiritual force protection" should begin during the training phase.

Naval Officer Arnold Resnicoff in Vietnam in 1969 (Provided photo)

The training would include a coldly realistic understanding of war. "I wanted to train to understand you're going to see things [in war] that are going to turn your stomach. Don't get used to it, take a stand against it."

He believes that all of us have "this compass that says you just have to do the best you can" even in horrible circumstances.

"None of us is going to be perfect. We're all going to be more cowardly than we think we are. We're all going to be more cruel than we think we are, given the right circumstances. You just do the best you can and just keep trying to forgive yourself — and then try again. It is a very complicated area, but that kind of boils down to: You're not perfect, you're not iron, you forgive yourself and don't give up. Keep going."

Spreading the message

His experience working through such religious and ethical thickets is reflected in an extensive curriculum he developed for the Naval War College titled "Faith and Force: Religion, War, and Peace." It comprises pages thick with daunting questions and dives deeply into material rarely associated in the public imagination with military training.

For instance, in a segment headlined, "Church and State, Land and Power," one question poses: In a nation which is based on a separation of church and state, on what basis can we justify a military chaplaincy — where salaries of clergy as well as a multitude of religious supplies, all come from tax money? (No answers are provided in the curriculum, but he goes into a lengthy explanation during a 2010 talk at the Library of Congress, which you can watch on their site.)

Arnold Resnicoff visiting children at Camp Hope in Albania (Provided photo)

And another question that might have special pertinence today: "Consider the concept of nationalism in relation to religion: Is the relationship sometimes complementary, or do the two ideas always exist in tension?"

Those questions lead, in the interview, to what he calls today's $64-million question: "When do we have to fight? When to intervene?" That question takes on significant elements today that were not part of the equation during the formation of what he terms "just war theories" and even military theory of the not-too-distant past.

He has addressed the question, he says, in papers delivered at the Naval War College. "In traditional just war theories, war should be a last resort. Today, I think we may not be able to say that anymore because the last resort may be too close to an attack that might mean annihilation. Maybe today it is enough to say it just should not be the first resort."

He recalls the story of Moses intervening when he sees a slave being beaten.

"Moses looked around to see if anyone else was reacting, and when he saw no one, he intervened. The Talmud said, 'Where there is no man, you be a man,' and I once knew a poet who translated that: 'Where there is no humanity, you be humanity.' So, I think that is a driving force in my theology, in my faith. Where you are, if there is no humanity, you be humanity, you be the force for good. I think that is at the heart of so much that I believe and which I try to teach."

It is a driving force that was a part of his theology those decades ago in Beirut.

"To understand the role of the chaplain — Jewish, Catholic or Protestant — is to understand that we try to remind others," he wrote, "and perhaps ourselves as well, to cling to our humanity even in the worst of times. We bring with us the wisdom of men and women whose faith has kept alive their dreams in ages past. We bring with us the images of what the world could be, of what we ourselves might be, drawn from the visions of prophets and the promises of our holy books. We bring with us the truth that faith not only reminds us of the holy in heaven, but also of the holiness we can create here on Earth. It brings not only a message of what is divine, but also of what it means to be truly human."

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor-at-large and the author of The Emerging Catholic Church: A Community's Search for Itself (2011) and Joan Chittister: Her Journey from Certainty to Faith (2015), both published by Orbis Books. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]