Volunteer Bud Courtney serves lunch at the Catholic Worker's St. Joseph House in New York City Dec. 4, 2018. The house of hospitality is near the Church of the Nativity, the parish of social activist and sainthood candidate Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Think you have a "Vatican II parish"?

For evidence, see the parish bulletin. Look at the notices for meetings, including for a justice and peace committee, Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) classes, other religious education, groups for divorced/separated and LGBT Catholics. Frequently, there are a lot of gatherings of God's faithful featured.

Yet Jack Jezreel argues you probably have a "Vatican I and-a-half parish." You are probably good at gathering, but not so good at sending off.

Here is his vision: A parish where people are inspired to transform the world, experience a preferential option for the poor and hold church far away from their parish buildings, perhaps on the other side of town where the homeless live and where survival is a constant struggle.

"Parishes can and should change the world," he writes in A New Way to Be Church: Parish Renewal from the Outside In, published by Orbis late last year.

Jezreel, the founder of JustFaith Ministries, a parish renewal program based in Louisville, Kentucky, argues that most parishes are too self-absorbed — good at gathering people together, not so good at sending them off on a mission.

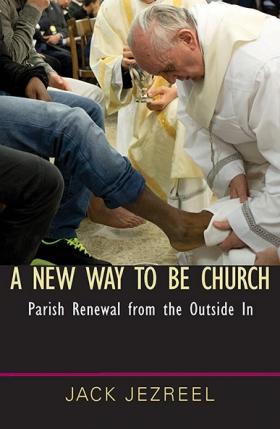

Cover of "A New Way to Be Church" (Orbis)

For Vatican II parishes to develop, said Jezreel, social ministry needs to be in the center of church life, not off to the side. Too often, parishioners are content to minister among themselves. "You and I live in a land of limbo between Vatican I and Vatican II," he writes.

Jezreel said his vision is inspired by the prophetic pronouncements of Pope Francis who, he said, "has essentially democratized discipleship" via incessant calls for Catholics to reach out to the margins. The famous image of the pope washing the feet of young people adorns the book's cover.

Jezreel, 62, grew up in Clearwater, Florida, in what he describes as comfortable circumstances and studied theology at University of Notre Dame. He describes his student days as being immersed in basic pleasures, such as $700 spent on eating out during his first semester.

Upon graduation, he became part of a Catholic Worker community in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and, after six years there, took a job as social minister at Epiphany Church in Louisville. He made the point in his interview with NCR that most Catholic parishes, particularly relatively affluent ones like Epiphany, don't take social outreach seriously enough.

The Catholic Worker, where he met his wife Maggie, created a lasting impact. The Catholic parish can learn much from its focus on community and direct service with the poor, writes Jezreel. Without that connection, parishes in more affluent neighborhoods will never become the vibrant centers of the Gospel they are meant to be, he said.

In traditional Catholic terms, it's the road to sanctity.

The example, he cites saints, both canonized and not, such as Damien of Molokai, the saint who aided lepers in Hawaii; Dorothy Day, the Catholic Worker from New York who ministered to the unemployed during the Depression; and Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle, the Los Angeles priest famous for working with gangs. All put themselves into direct contact with the poor and forgotten.

"Most holy people spend a big part of their faithful lives with those who have been somehow abandoned or excluded," he writes.

Advertisement

Jezreel argues that parish life can be directed toward the goal of social mission, such as religious education — where students can work on service projects — to marriage preparation, where couples in preparation can look beyond their own relationship and spend time practicing charity and learning about social justice at the local soup kitchen or homeless shelter.

Catholics seeking a social mission often find it in varied groups such as the Catholic Worker, Jesuit Volunteer Corps, Catholic Relief Services, Maryknoll and other mission organizations and religious orders built around charitable and social justice works. It's a wonderful part of Catholic tradition, but it frequently leaves out the parish. Often, writes Jezreel, those inspired by such contacts "feel like strangers in a strange land" when returning to parishes.

The power of the Catholic parish will remain largely untapped if it continues to be a self-absorbed community, said Jezreel.

"Food stamps is not the crescendo response to poverty, community is. What we all desire is not just food but sharing a meal with people we care about who care for us," writes Jezreel.

Speaking to NCR, Jezreel notes that the vision of the Vatican II parish, promoted by Francis, faces inertia as its greatest obstacle. But without change, parishes will continue to lose young adults who increasingly find that they have little connection to the church.

One aspect of a Vatican II parish is downward mobility. Jezreel cites St. André Bessette Parish in downtown Portland, Oregon, with its mission to the homeless (its parish website notes its weekly "Red Door Cinema" movies for everyone as well as haircuts). Jezreel and his family — he and his wife have three adult daughters — attend St. William's in Louisville, "a place you wouldn't want to be if you didn't care about the poor."

It may sound idealistic and impractical. One objection he's heard is that most working Catholics don't have enough time and energy to embrace such an ambitious agenda. But the alternative guarantees steady decline.

"The old wineskins, the old parish structure, is dying," he said.

Jezreel has spoken at hundreds of parishes around the country. Over a span of just a decade, the loss of young adult parishioners is apparent in most of them.

"I am shocked by the loss of membership in such a short time," he said. "The old model of parish just doesn't work. It isn't compelling."

One model borrows from religious communities, which often grew from a particular work, such as hospitals or education. Parishes, said Jezreel, can adopt hard-pressed communities. One example, he said, could be struggling single mothers, for whom a parish could establish a particular mission, offering regular outreach and support.

"The challenge is how we create a scenario when we are always being connected with those in harm's way," he said. The road to a true Vatican II parish, according to Jezreel, remains a path moving toward downward mobility.

[Peter Feuerherd is a correspondent for NCR's Field Hospital series on parish life and is a professor of journalism at St. John's University, New York.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time The Field Hospital is posted. Go to this page and follow directions: Email alert sign-up.