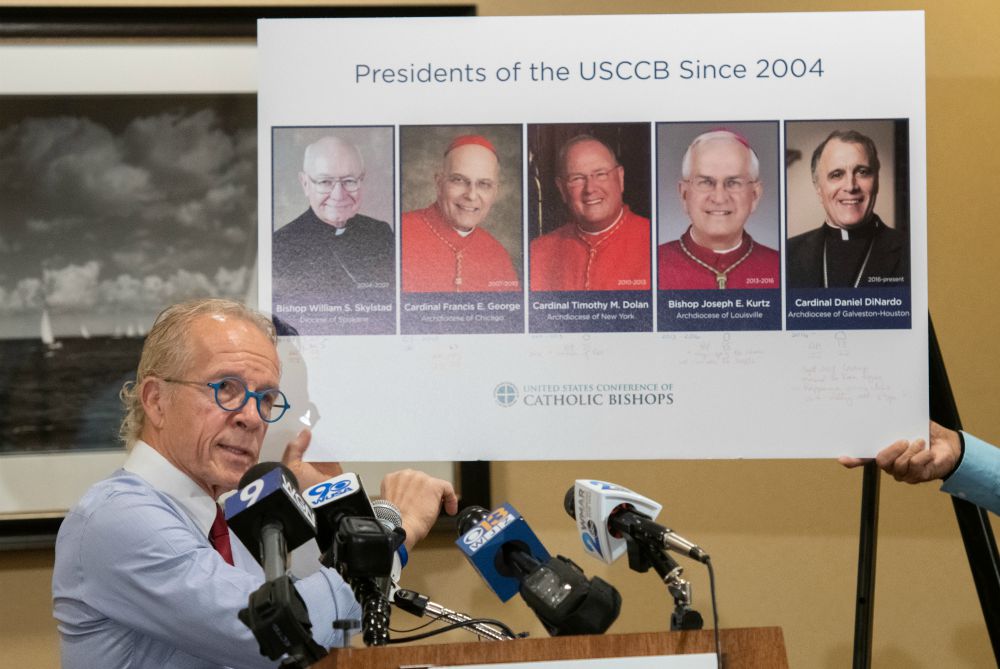

Attorney Jeffrey Anderson holds a placard reflecting U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops leadership since 2004, during a Nov. 14, 2018, press conference in Baltimore. (CNS/Catholic Review/Kevin J. Parks)

When the Rochester Diocese became the first in New York State to file for bankruptcy in September, it didn't come as a surprise to legal experts. With the state passing the Child Victims Act in August, extending the statute of limitations for sex abuse victims, the diocese was served with hundreds of lawsuits alleging abuse, dating back decades.

Reeling under the financial weight of clerical sexual misconduct lawsuits, Rochester joined a list of other dioceses across the country that have also filed for bankruptcy protection.

While not surprising, bankruptcy declarations, say victim advocates and legal scholars, deny victims their day in court, cover up wrongdoings and result in lower settlements.

Financial distress is not always the reason a diocese declares bankruptcy. The procedure can be used for a variety of purposes often beneficial to a diocese that wants to avoid the discovery that might be required in a trial, as a means of financial reorganization, or as a path to dealing in the most efficient way with groups of complainants.

Bankruptcy can be used, experts say, to help push aside litigation. Jeff Anderson — a Minnesota-based attorney who represents survivors of clerical sex abuse against the Catholic church across the U.S. — said bankruptcy cases are often used to accomplish financial reorganization.

"When a diocese files for [financial] reorganization, it is done because they are facing a trial in which their history will be revealed. A way they can stop that trial is to file for reorganization. In Portland [Oregon], Davenport [Iowa] and other places, that's exactly what they've done," said Anderson.

Under bankruptcy laws, there's a temporary stop to litigations, giving diocesan authorities time before testifying under oath, and limiting the public release of documents highlighting abuse and cover-up. As a result, victims generally wait longer to see a legal resolution of their cases.

And once a judge puts a freeze on litigation, including discovery depositions, turning over documents and court hearings, the public conversation on abuse and cover-up shifts to finances.

"Instead of focusing on the needs of the victims that were created by the diocese, the focus is on the holdings, in the wealth of the diocese," said Marci Hamilton, CEO and academic director at Child USA, a non-profit academic thinktank at the University of Pennsylvania dedicated to research to prevent child abuse and neglect.

In a bankruptcy filing, the diocese has to reveal the full extent of its financial resources, determining how much is available for survivors to get in potential settlements.

Appearing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court with his lawyers, Bishop Salvatore Matano of Rochester filed a petition for Chapter 11 reorganization bankruptcy. The petition estimated assets of the diocese between $50 million and $100 million, and its financial liabilities from $100 million to $500 million. In a letter to parishioners, Matano said the diocese was filing for bankruptcy because the costs of litigation and settlements exceeded the church's resources.

In the Diocese of Rochester, each parish is incorporated as a separate entity under New York state's Religious Corporation Law, meaning the assets of the parishes are not included in the diocese's bankruptcy filing.

"That's the assets that have to be used to make payments to victims," said Dominican Fr. Thomas Doyle, a longtime activist on sex abuse issues in the church.

The Rochester Diocese has been putting money into the parishes, schools, Catholic Charities and other institutions. Since they are incorporated as separate entities, legally they don't come under the fiscal control of the bishop. As a result, a diocesan bankruptcy filing does not have an impact on parishes. A spokesman for the Rochester Diocese said he could not comment because of ongoing litigation.

Advertisement

"It is similar to what Dolan had done in Milwaukee," said David Clohessy, former national director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP).

In 2007, when Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York was the archbishop of Milwaukee, he transferred $57 million of archdiocesan funds to a cemetery trust fund in an apparent attempt to protect the money from lawsuits. Similarly, in May 2016, the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis was accused of hiding $1 billion in assets when they filed for bankruptcy.

Although parishes and other organizations in the diocese are separately incorporated, a bishop leading a diocese retains control of all finances and cannot claim that a parish is totally divorced from him, said Doyle. In such cases, victims also sue the parish where the abuse occurred.

According to Hamilton, "The argument made here is the parish doesn't have any assets to pay for the litigations, and the diocese is protected because the parish is a separate entity. So, the question here is: Are the dioceses essentially throwing the parishes under the bus?"

Not really, said David Skeel, professor of corporate law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. "It would depend on how much the diocese contributes to its individual parishes, and my guess is that it varies. If the parish isn't in bankruptcy and if it's separately incorporated, there doesn't necessarily have to be significant financial effect," said Skeel.

Those employed by the diocese may not be affected either. "That's going to depend a lot on the particular circumstances. If it's an otherwise healthy diocese, employees will not suffer," said Skeel.

Bankruptcy protection, said Doyle, comes from the "playbook" that the bishops have used in the past.

"It comes from their understanding of the nature of the church, where they see themselves as essential to the institutional church. And the institutional church, the structure, deserves absolute protection. And this has been going on, at least in our era, for 35 years," he said.

Part of also what makes bankruptcy so beneficial to the church facing abuse suits is the "bar date" — a date set by the court by which time a creditor must submit a proof of claim. This requires all victims out into the public to be part of a settlement. The process becomes more damaging to victims, said Hamilton, who said that the Federal Bankruptcy Code should not be permitted to be levied against child sex abuse victims.

Bishop Salvatore Matano is assisted by Deacon Peter Van Lieshout, left, during his Jan. 3, 2014, installation Mass as ninth bishop of Rochester, New York, at Sacred Heart Cathedral. (CNS/ Catholic Courier/Mike Crupi)

In Milwaukee, victims were asked to come forward during the bankruptcy filing. But later, many claims were rejected due to the statute of limitations. "They [the diocese] did everything they could to prevent any sense of justice for the victims. That was a debacle. It retraumatized so many," said Doyle.

In the case of Rochester, since most parishes were incorporated around 10 years ago or more, it's going to be harder for victims to challenge parishes' fiscal independence. But Anderson said that his client victims are prepared to sue parishes.

Skeel pointed to the impact of the First Amendment, creating a limitation on how much courts will intervene in the financial affairs of a religious institution. "There are questions about how involved can the court get, how much disclosure can they insist on, how intrusive can the discovery process be? Is there any way you could ever put a trustee in place? But you couldn't replace the bishop in a diocese."

As a way forward, Clohessy suggested that bishops welcome independent monitors to come in and look over diocesan finances. And, he said, if necessary, they should borrow the money to pay victims. "They should ask the flock for special collection. They should sell all the extra land and buildings and hidden assets. And then, if they still say, 'We got to declare bankruptcy,' well, at least you made an effort," he said.

[Sarah Salvadore is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is ssalvadore@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @sarahsalvadore.]