A demonstrating church member is arrested after Samuel Oliver-Bruno, 47, an undocumented Mexican national, was arrested after arriving at an appointment with immigration officials, in Morrisville, N.C., on Nov. 23, 2018. (AP/Travis Long)

Houses of worship that provide sanctuary for undocumented immigrants at risk of deportation follow strict protocols for protecting their guests from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents tasked with enforcing immigration laws.

Doors must stay locked at all times. Volunteers must be present 24/7, and they must undergo training on how to respond should ICE come knocking.

So far, it's worked: Since the re-emergence of the sanctuary movement in 2014, no undocumented immigrant taking sanctuary in a church has been arrested on its premises.

But on those occasions when undocumented people have stepped out of church sanctuary, they have promptly been jailed and deported.

On the day after Thanksgiving, Samuel Oliver-Bruno left a Durham, N.C., church where he was taking sanctuary for fingerprinting at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

With the help of a pro bono lawyer and an immigrant advocacy group, Oliver-Bruno, a 47-year-old husband, father and lay minister, had applied for a deferral of his deportation on humanitarian grounds because his wife is ill. When he arrived at the USCIS office Friday (Nov. 23), he was tackled and whisked into a van by four plainclothes ICE agents, as church members who accompanied him watched in horror. After a two-hour peaceful standoff, his protectors, who had surrounded the van, were arrested and Oliver-Bruno was taken away.

After spending a few days at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., he was transferred to a detention facility in Brownsville, Texas, on Thursday. Homeland Security has denied Oliver-Bruno's petition for deferred deportation and he is expected to be deported back to Mexico. He has spent more than two decades in the U.S., working in construction and caring for his wife, Julia Perez Pacheco, who has lupus and complications from open-heart surgery.

But since Oliver-Bruno's arrest, sanctuary churches are doubling down on their security protocols.

"There were some (church volunteers) saying, 'If he needs to go to a dentist, let's just put him in a car and take him to a dentist,' " said the Rev. Doug Long, pastor of Raleigh's Umstead Park United Church of Christ, where Eliseo Jimenez, an undocumented man, has been living since October 2017. "I don't think people are having that conversation now."

This week, Isaac Villegas, pastor of Chapel Hill Mennonite Fellowship, devised a rapid response text messaging service for allies and advocates for undocumented people in sanctuary. By registering for the SMS service, a leader can broadcast an alert asking people to show up to a site of an ICE arrest. As of Wednesday, 350 people had signed up.

"It takes a community to keep us safe," said Villegas, whose church is providing sanctuary for an undocumented woman along with a Presbyterian church. "We need to learn how to do that well."

There are 36 churches across the country providing sanctuary for an estimated 52 undocumented people, according to Church World Service, a multidenominational Christian ministry that works on immigration and other social justice issues. Hundreds of other supporting congregations, including synagogues and mosques, provide volunteers, meals and financial support to people in sanctuary.

For years, churches — along with schools and hospitals — have benefited from a 2011 "sensitive locations" memo that has prevented ICE from arresting, searching or interviewing people in houses of worship.

Advertisement

But outside the church safety zone, the atmosphere, if not the rules of engagement, have been changing.

In April 2017, a pastor and a lawyer accompanied an undocumented immigrant for a scheduled check-in at an ICE office in Phoenix. At the end of the check-in, ICE ordered the man, Marco Tulio Coss Ponce, to get an ankle monitor and when he walked two blocks to another office to be fitted, he was quickly arrested and deported to Mexico.

"As soon as they isolated him, they detained him and deported him," said the Rev. Ken Heintzelman, pastor of Shadow Rock United Church of Christ in Phoenix.

Heintzelman, whose church has provided sanctuary to multiple undocumented individuals and families, said that up until then, he and his congregation enjoyed a good relationship with ICE.

Under the Obama administration, ICE frequently dropped off asylum-seekers at his church once they were released from custody. Today, Heintzelman said, he no longer trusts the agency.

"The advice I would give is that undocumented people need to do their best to stay in sanctuary and let advocates — their attorneys — go in their stead," he said.

Church leaders were especially alarmed at last week's ICE arrest of Oliver-Bruno because it took place at the USCIS office, not in an ICE office. Furthermore, USCIS had sent Oliver-Bruno a letter asking him to appear for fingerprinting at 9 a.m. Nov. 23 as part of his application for deferred deportation.

"If you fail to appear as scheduled, your application, petition or request will be considered abandoned," the form letter said.

That sent Oliver-Bruno into a trap, said U.S. Reps. David Price and G.K. Butterfield, who represent parts of Durham, in a statement. The two congressmen also criticized Oliver-Bruno's arrest by pointing out that "it appears ICE has acted in concert with officials at USCIS."

Noel Andersen, national grassroots coordinator for Church World Service, said he doesn't remember another such incident.

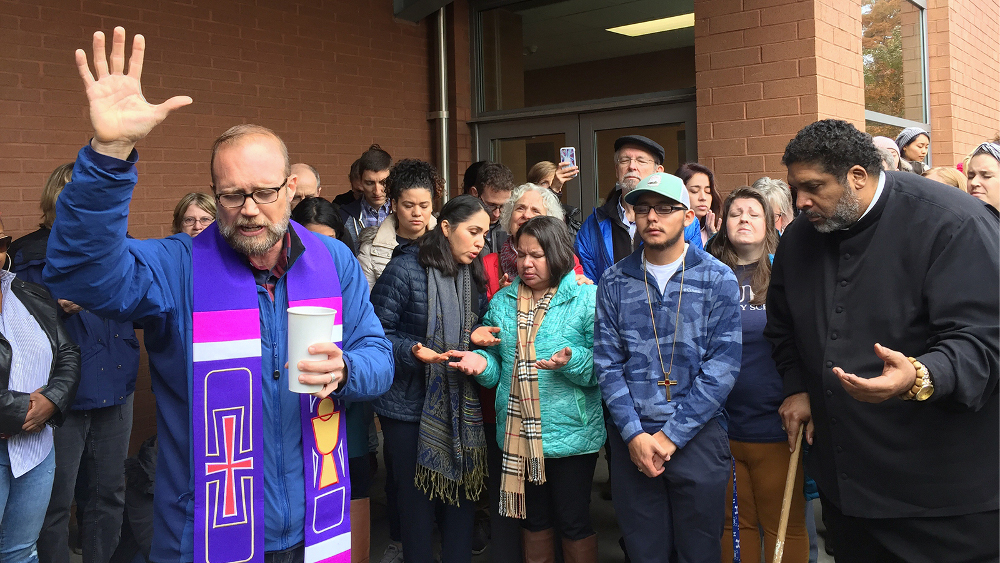

Cleve May, left, pastor of CityWell Church, flanked by Samuel Oliver-Bruno’s wife and son with the Rev. William Barber II, right, at a protest outside the Wake County Detention Center in Raleigh, N.C., on Nov. 26, 2018. (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

"USCIS is supposed to assist immigrants in becoming citizens, not set them up for deportation," Andersen said.

Recently, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a class-action lawsuit alleging officials for the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services have been coordinating with their counterparts at ICE to facilitate arrests at citizenship offices in New England.

USCIS spokesman Michael Bars declined to comment on Oliver-Bruno's case, saying that the agency doesn't comment on pending litigation.

As Oliver-Bruno awaits what appears to be imminent deportation, his case is drawing an impressive outpouring of support from local civic leaders, including Durham's Mayor Steve Schewel. Even the dean of the Duke Divinity School, L. Gregory Jones, wrote a letter demanding he be released from custody so he can return to his family. (Oliver-Bruno had worked toward a certificate from Duke Divinity School's Hispanic-Latino/a Preaching Initiative while in sanctuary.)

CityWell Church, the United Methodist congregation that provided Oliver-Bruno sanctuary for 11 months, has held a series of vigils to protest the arrest — including one Tuesday outside the local ICE office in Cary, N.C.

The vigils have brought out hundreds of Christians, Jews and secular activists to denounce ICE's tactics and more generally the government's hard-line immigration policies.

Not all church leaders are convinced that confrontation is the best path forward.

"I don't like what ICE does," said Long, the Raleigh pastor. "But if we're putting people in the corner then we're shooting ourselves in the foot in the long run."

And even those close to Oliver-Bruno are recognizing that churches, even in their increased vigilance, must work in line with their principles.

"We must unmask the violent immigration policies of this nation," said Alma Ruiz, a friend of Oliver-Bruno who spoke at Tuesday's rally from the bed of a truck. "We must do it in a peaceful, powerful and prayerful way."