Fr. Fredis Sandoval, a Salvadoran priest and founding member of the Concertación Romero is pictured after an interview with NCR March 8 at St. Sabina Parish in Belton, Missouri, during a visit to the United States for St. Sabina's annual Romero mass and celebration. (NCR/James Dearie)

Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero's "vision of the church of the people" is "a legacy not only anchored in the past but also a challenge for the present and the future," said Fr. Fredis Sandoval, a Salvadoran priest and founding member of an organization that promotes justice in the case of Romero's assassination.

Speaking to NCR on March 8 in an interview conducted in Spanish, just a day after the Vatican announced that Pope Francis had approved the declaration of a miracle through Romero's intercession, clearing his path to sainthood, Sandoval described the upcoming canonization as a joy and a vindication for those who have long considered the archbishop a "prophet, pastor and martyr" but also an opportunity to honor his legacy by adapting his message to current issues.

Sandoval, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Romero and currently serves as chaplain and professor at a Catholic school in San Marcos, El Salvador, knew Romero as a kind and generous pastor who met with him regularly while he was a minor seminary student in the Santiago de María Diocese where Romero was bishop.

When Romero served as archbishop of San Salvador, the nation's capital, from 1977-1980, Sandoval was also present in the city studying philosophy and witnessed Romero's increasing outspokenness in support of the poor and against the violence being perpetrated by the government.

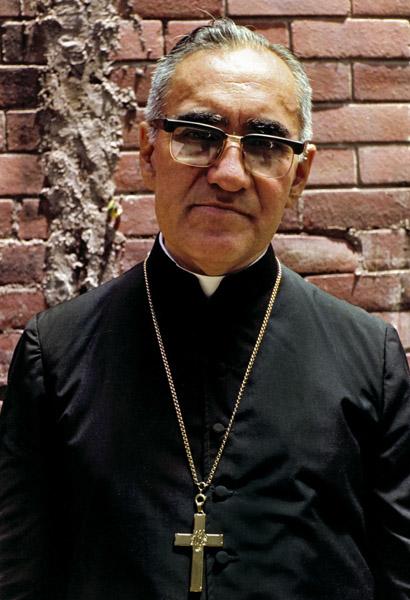

Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is pictured in a 1979 photo in San Salvador. (CNS/Octavio Duran)

This outspokenness eventually led to Romero's death. On March 24, 1980, just weeks after he sent a letter to U.S. President Jimmy Carter asking him to withhold aid to El Salvador's military, and a day after he gave a homily, broadcast on the radio, begging soldiers to disobey immoral orders, Romero was shot and killed while saying Mass.

The Salvadoran government has yet to prosecute anyone for Romero's murder, although the perpetrators, some already deceased, are widely known due to information gathered by a U.N. Truth Commission, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and a civil case in the U.S. Federal District Court in Fresno, California.

"We in El Salvador know the historic truth. We know who it was, how they operated, when they did it," said Sandoval. "We think that knowing the historic truth isn't enough. We have to know the truth at the judicial level."

Sandoval helped found the Concertación Romero (Romero Coalition) in 2009 to push the government to take action. Some progress is finally being made after El Salvador's Supreme Court in 2016 declared unconstitutional a 1993 amnesty law that had blocked prosecutions and a judge reopened Romero's case in 2017.

Since his death, Romero, while honored as a saint and martyr by many Salvadorans and others, has also suffered attacks on his reputation. Some opponents spread lies about the archbishop and even send packets of anti-Romero materials to the postulator for his sainthood cause, said Sandoval.

These kind of attacks "happened to Jesus, it happened to all the saints, and it also happened to Romero," said Sandoval, but he noted that acceptance of Romero has increased after Pope Francis declared him a martyr, paving the way for his beatification and reenergizing a sainthood cause which had stalled for years.

However, Sandoval cautioned, acceptance of Romero is not enough.

Women hold images of slain Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero during a march to celebrate what would have been his 92nd birthday in San Salvador, El Salvador, Aug. 15, 2009. The event marked the beginning of activities to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the archbishop's death. (CNS/Luis Galdamez, Reuters)

Within the church, he said, some try to understand a saint in order to be moved, inspired and encouraged on their faith journeys, but "with time, these practices start degenerating into a form of spiritualization." Saints are confined to altars and prayer cards and the faithful forget "what martyrdom and prophecy mean."

"Those who begin to get to know him starting at the beatification or canonization, have a greater risk of reducing themselves to these aspects," Sandoval added. "So, I believe it should be a pastoral focus of the churches … to make sure that this doesn’t happen with a prophet and martyr … so we don't stay looking only at the past, or looking at the canonized saint, but understanding God's message for us today."

"I say it's a legacy and it's a program, also, for action of Christians in the church and with the Salvadoran people," Sandoval said. He is concerned that this understanding is sometimes missing in discussions of Romero, even within the Salvadoran church.

For example, while the Salvadoran church established a well-intentioned program to help people familiarize themselves with Romero in preparation for his beatification, the plan lacked a pastoral dimension to help people discover what Romero's teachings ask of them today, said Sandoval. This became evident when the murder rate in El Salvador skyrocketed shortly after Romero's beatification in 2015 and the church response remained weak.

"Romero would have been extremely worried," Sandoval said. "He would have increased his denunciations, not only of the criminal acts, but also what are pastors, the church, authorities, organs of the state, doing in the face of this situation?"

Romero, who once identified 10 types of violence in a pastoral letter, would also have ordered a detailed analysis of the situation, said Sandoval, asking "who is responsible, what are the consequences, and how do we confront this?"

Fr. Fredis Sandoval stands with participants in St. Sabina Parish's 11th annual celebration of Blessed Oscar Romero held March 10, in Belton, Missouri. (Courtesy of St. Sabina Parish)

"Currently many leaders, including many members of the church hierarchy, don't distinguish the differences in the victims, in the causes, in the consequences, in those responsible, and that makes it more difficult to confront them. A poorly understood problem is a solution that's not going to arrive," said Sandoval. Romero "would have reacted much more, discussing intensely to understand the situation and how to illuminate and transform it."

Sandoval compared this approach to the good Samaritan, who, instead of passing on the other side of the road, approaches, knowing that it is necessary to get close to a problem in order to understand it and figure out how to alleviate it.

Sandoval emphasized that this technique has universal relevance.

Advertisement

Romero's "reaction to a problem, his method toward a problem, his vision of a problem, also challenges everyone," Sandoval said, "and this also helps us see him in a more universal context that represents all human thought and activity. Now that the canonization is near, I think that can help this dimension better shine."

Sandoval added that foreign visitors to Romero-related sites in El Salvador who "go with an attitude of faith, of openness, even of searching, that their contact with these people, with these places, with this event, tells us something for our present day, for our journey," inspires Salvadorans "to be a little more responsible toward the saint that we now have."

A Mexican priest once told Sandoval that Romero was like a "fountain" and Salvadorans have a particular duty "to make sure that this fountain functions, and that it offers what it has to the whole world — light, life, grace, new processes of transforming history."

[Maria Benevento is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is mbenevento@ncronline.org.]