Pope Francis, flanked by Vice President Joe Biden and House Speaker John Boehner of Ohio, waves to the crowd on Capitol Hill in Washington, Thursday, Sept. 24, 2015, as they stand on the Speaker's Balcony on Capitol Hill, after the pope addressed a joint meeting of Congress inside. (AP/Susan Walsh)

Pope Francis, the first pope from the New World, has a more expansive view of what we call the Western world than his predecessors. He organized a major ecclesial summit on the Amazon region in South America, and his concern with capitalism and racism, while these issues are not unknown in Europe or Asia, seems pointed at the American manifestations of these ills.

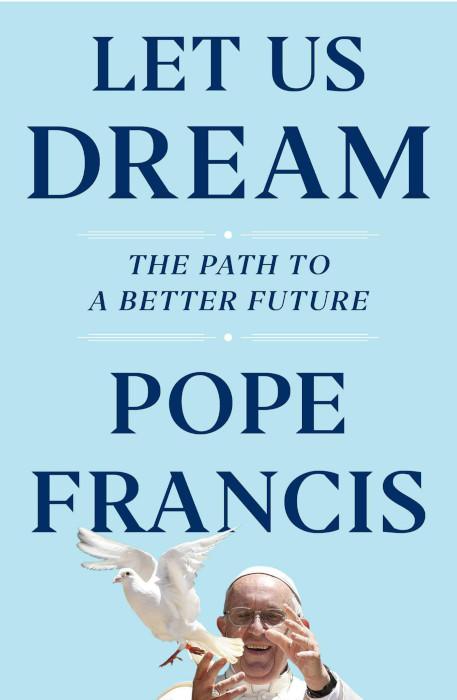

We can see this in Francis' new book, Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future, published Dec. 1, as he weighs in on the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as controversial topics such as military spending, abortion, police violence, the treatment of migrants and refugees, protest movements and the role of women.

Readers will be surprised how relevant the book's message is to American Catholics and the country's leaders.

Since the United States spends more on the military than any other country, he is clearly thinking of us when he urges the reader to look at "what a nation spends on weapons, and your blood runs cold."

And since we produce and sell more weapons than any other country, his condemnation of the arms trade hits home. "The astonishing amounts spent on the arms trade could be used to feed the whole of the human race and school every child," he laments. "Arms spending destroys humanity."

He also recalls his 2015 address to the U.S. Congress, in which he condemned capital punishment and expresses shock that "even Christians try to justify it."

Francis also believes COVID-19 should be taken seriously. He notes that the pandemic has hit women harder "because they are more likely to be on the front line of the pandemic" as health care workers. They are also "harder hit economically."

At the same time, he reports, "The countries with women as presidents or prime ministers have on the whole reacted better and more quickly than others, making decisions swiftly and communicating them with empathy."

His experience has taught him that "women in general are much better administrators than men. They understand processes better, how to take projects forward."

He singles out women economists for special praise as their "fresh thinking is especially relevant for this crisis." His comments seem to align with President-elect Joe Biden's nomination of women to top economic jobs in his administration, including the first female Treasury secretary, and women named to head up the the Council of Economic Advisers and the Office of Management and Budget.

"Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future" by Pope Francis. (Courtesy image)

He refers to economists such as Mariana Mazzucato and Kate Raworth, who have influenced his thinking by challenging "our culture's unthinking obsession with growth in gross domestic product (GDP) as the single overriding goal of economists and policymakers."

Women should also be listened to in the church. "In my pastoral experience on different Church bodies," he says, "some of the sharpest advice came from women who were able to see from different angles, and who were above all practical, with a realistic understanding of how things work and people's limitations and potential."

Francis sounds a bit defensive as he describes at length the women he has appointed to positions in Rome and earlier in Buenos Aires. Although he sees a role for women as leaders in the church, "To say they aren't truly leaders because they aren't priests is clericalist and disrespectful."

Francis also returns to his core concern of migrants and refugees, another controversial topic in the United States whose situation has been made worse by COVID-19. "When the virus hits a refugee camp," he complains, "it's an injustice that cries to heaven."

The lockdown imposed because of the pandemic has shown, he writes, that "the basic needs of the most developed societies are being met by poorly paid migrants, yet they are scapegoated and denigrated, and denied the right to safe and decent work." This is certainly true in the U.S.

"We need to welcome, promote, protect, and integrate those who come in search of better lives for themselves and their families," he says.

He ties the issue of abortion to migration, although he recognizes "many will be irritated to hear a pope return to the topic" of abortion.

"The arrival of a new human life in need — whether the unborn child in the womb or the migrant at our border — challenges and changes our priorities," he writes. "With abortion and closed borders we refuse that readjustment of our priorities, sacrificing human life to defend our economic security or to assuage our fear that parenthood will upend our lives."

Francis is disappointed that while some support one or the other, so few support both the unborn child and the migrant.

In another explicit reference to America, the pope condemns the "abuse of power which we saw in the horrendous police killing of George Floyd." Francis speaks positively of the protests around the world that followed Floyd's death. "Many people who otherwise did not know each other took to the streets to protest, united by a healthy indignation."

Msgr. Ray East, pastor of St. Teresa of Avila Catholic Church in Washington, speaks during a prayerful protest outside the White House June 8, 2020, following the police killing of George Floyd, a Black man. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Although the pope does not explicitly mention the Black Lives Matter movement, grassroots movements get extensive treatment in his book. While condemning "the fallacy of making individualism the organizing principle of society," he asserts, "We need a movement of people who know we need each other, who have a sense of responsibility to others and to the world."

But not all movements should be embraced. "In interpreting and praying over events or trends in the light of the Gospel, we can detect movements that reflect the values of God's Kingdom or their opposite."

We should look for movements that "hunger and thirst for righteousness," he writes, quoting from the Gospel of Matthew. "If we discern in such a yearning a movement of God's Spirit, it allows us to open up to that movement in thought and action, and so create a new future according to the spirit of the Beatitudes."

He urges "the Church to open its doors more widely to these movements ... offering teaching and guidance, but never imposing doctrine or trying to control them."

But movements "marked by their rigidity and authoritarianism" are to be avoided. He notes that even in the church, "Leaders and other members presented themselves as restorers of doctrine and of the Church, but what we later learn of their lives tells us the opposite."

Also to be avoided are movements that bring out "an angry spirit of victimhood," he writes, calling out groups that refused to wear masks and "protested, refusing to keep their distance, marching against travel restrictions — as if measures that governments must impose for the good of their people constitute some kind of political assault on autonomy or personal freedom!"

Francis also urges those who want to tear down statues to slow down. "Those who pulled down statues did so to draw attention to the wrongs of the past, and to deny honor to those who committed those wrongs," he acknowledges.

"But this should be done through consensus building, by debate and dialogue rather than acts of force," he writes.

"Let's look at the past critically but with empathy, to understand why people took for granted what now seems to us abhorrent," he urges, referring, I believe, more to statues of Junipero Serra, rather than Confederate generals. "And then, if we have to apologize for the mistakes made by institutions of that time, we can do so, but always keeping in mind the context of the time."

Francis sees in such movements "a source of moral energy, a reserve of civic passion, capable of revitalizing our democracy and reorienting the economy." He sees them as "an army with only the weapons of solidarity, hope, and a sense of community." These are encouraging words for young Americans.

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]

Editor's note: You can sign up to receive an email every time a new Signs of the Times column is posted. Sign up here.

Advertisement