Catherine Coleman Murphy, center, and Jack Wintermyer, right, protest along with others outside Cathedral Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul before an Ash Wednesday Mass in Philadelphia on March 9, 2011. (AP/Matt Rourke)

Many Catholic bishops and priests are frustrated by the continued coverage of the sex abuse crisis in the media. They believe they have fixed the problem and the church should be able to move on.

They argue that since the widespread mishandling of abuse in the Boston Archdiocese was exposed in 2002, the church in the United States has put in place policies and procedures to deal with abuse.

It's true that many precautions have been taken. Seminarians and priests, as well as employees and volunteers who work with children, must now go through a police background check. Any accusations of abuse must be reported to law enforcement. In some states, clergy are now mandatory reporters and will be prosecuted if they do not report abuse.

Any accusations of abuse must also be reported to a diocesan lay review board. If the board considers the accusation credible, the priest must be suspended while an investigation takes place. While suspended, he cannot do any ministry. The results of that investigation must be presented to the review board, which then makes a recommendation to the bishop.

If there is sufficient evidence of abuse, the priest is permanently suspended, and the case goes to the Congregation for Doctrine of the Faith in Rome, which decides whether to kick him out of the priesthood. If the case is unclear, the congregation might call for a canonical trial, either in the diocese or in Rome. If the priest is found guilty, he is thrown out of the priesthood, with some exceptions for elderly or sick priests. In any case, he would never be returned to ministry.

Critics say that these policies may be in place, but question whether they are being enforced. To read news accounts and grand jury reports, it doesn't look like it.

The bishops and their defenders point out that almost all of the abuse cases reported in the news and grand jury reports are old cases. Most of the cases in the Pennsylvania grand jury report, for example, were decades old: Of the 300 priests with accusations of abuse, only two had been accused of committing abuse in the last 10 years. Almost half the priests are dead. All are out of ministry.

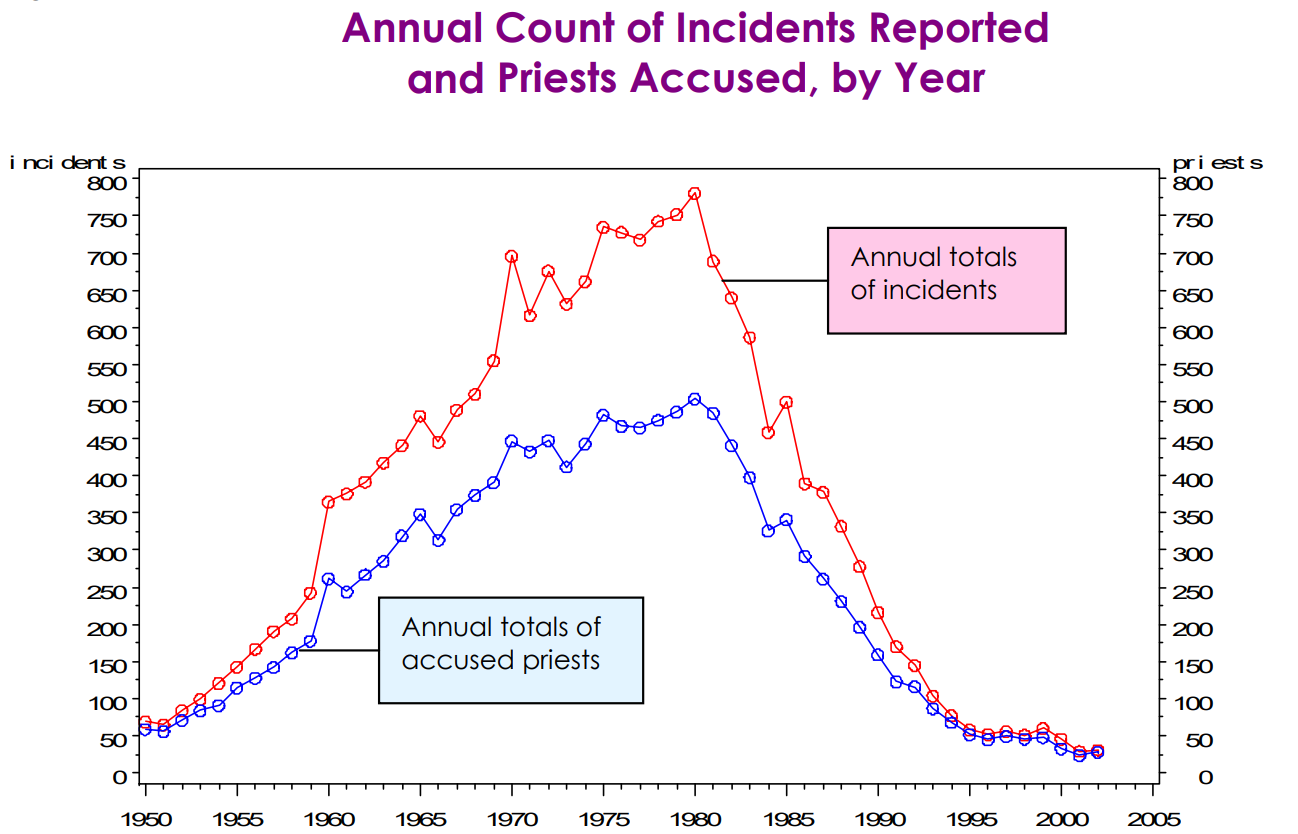

The bishops also point to the research done by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, which looked at allegations of clerical abuse between 1950 and 2002. It found that "more abuse occurred in the 1970s than any other decade, peaking in 1980." It showed that the number of cases plummeted in the 1980s and 1990s, long before The Boston Globe's expose in 2002.

Advertisement

Figure 2.3.1, “The Nature and Scope of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests and Deacons in the United States,” John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2004

When the John Jay study was published in 2004, critics predicted that as time went on, victims from later periods would come forward showing that the amount of abuse in the later decades was similar to that of earlier periods. The John Jay study acknowledged that possibility.

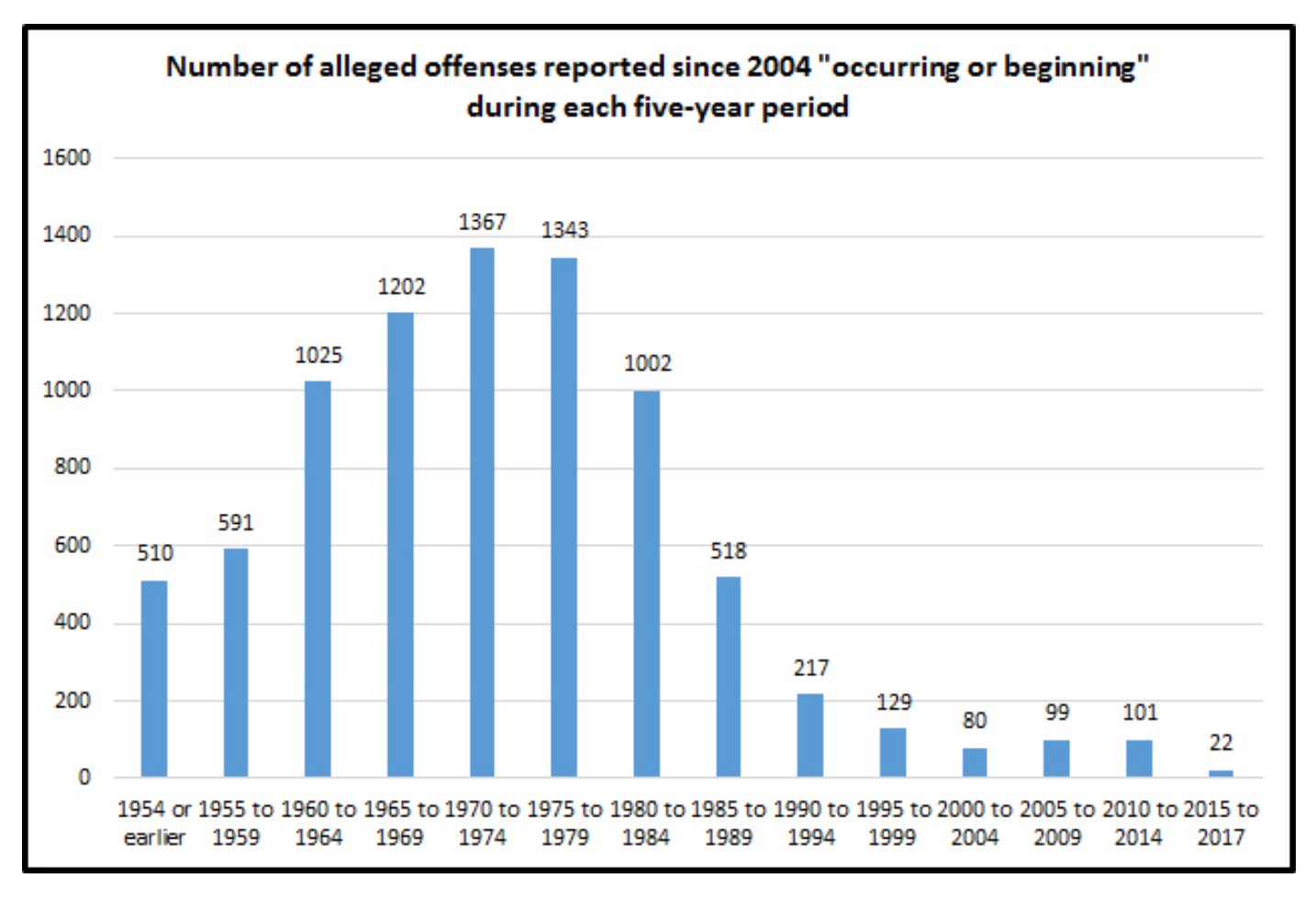

The Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate has continued collecting data on abuse since 2004 and reported 8,694 new allegations from 2004-2017. But, it found, "The distribution of cases reported to CARA are nearly identical to the distribution of cases, over time, in John Jay's results," according to Mark Gray of CARA. "The accusations continue to fit the historical pattern."

If the critics were right, there should have been more abuse cases in later years. "We'd expect the trend to move forward in the last 15 years if reporting delays were evident," writes Gray on his blog 1964, "but this has not been the case. No new wave of allegations similar to the past has occurred to date."

Of the 8,694 new allegations recorded by CARA since 2004, only 302 were for abuse taking place between 2000 and 2017, an average of 17 per year for the whole country. This is 302 too many, but nothing like the thousands of cases in the past.

Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University, 2018

Critics continue to challenge these conclusions, saying that in time new victims will come forward reporting more recent crimes. The bishops' defenders argue that the data shows that most bishops were quietly beginning to deal with abusive priests in the 1980s and 1990s. By 2002, negligent bishops such as Cardinal Bernard Law of Boston were the exception.

Despite the data, the public impression is of a church incapable of getting its house in order. Only those who carefully read news stories and grand jury reports will notice the dates of when the abuse took place. If a bishop challenges this impression, he is condemned as just not getting it.

The continuing problem, in other words, is not that the precautions aren't working. It's that the bishops have forfeited their credibility. People don't believe a thing the bishops say, and people are not going to let the church move on. Things might have been different if bishops in the past had been more forthcoming, taken responsibility for their actions and resigned.

Law enforcement officials in at least seven states are now launching their own investigations similar to the one in Pennsylvania.

There is only one way the bishops can begin to regain credibility, and that is to give a full and credible account of past abuse. Each diocese must publish the names of priests credibly accused, what they were accused of, when the diocese learned of the abuse, and what the bishop did.

Such a report should not be done by a chancery monsignor. It must be done by someone with credibility in the community— a retired judge, prosecutor, FBI agent or the like. Only when all the information is out will people begin to believe that the church has got things under control.

There is great opposition from bishops, priests and diocesan lawyers to such a full disclosure. But a smart bishop would get this report out before his attorney general comes knocking. In addition, such full disclosure is important in the healing process for victims of abuse. Bishops hurt them by stonewalling and denying their experience. Now it is time for the bishops to validate their experience by full disclosure.

[Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese is a columnist for Religion News Service and author of Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.]