Sr. Judith Auma, a member of the Little Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi, plays with two children on Jan. 17 at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya on the border with Uganda. Religious sisters are taking care of abandoned children, especially those born out of incest. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Editor's note: This story contains references to incest, rape and abuse.

It's 8 o'clock in the morning, and Sr. Judith Auma sits in one of the dormitories at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home. She holds one of the babies upright and maintains eye contact so he feels loved and safe before she feeds him with infant formula.

"This is what I do every day to babies who live here because they have been abandoned by families who could not care for them," she said, referring to St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home, located several hundred miles west of the country's capital, Nairobi, in the busy town of Busia.

Auma, a member of the Little Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi, said the home started in 2021 to ensure all orphaned, vulnerable and abandoned babies can grow up in loving and healthy families in the metropolitan border town between Kenya and Uganda.

St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home is under Amukura Orphanage Home, which also cares for newborn babies whose mothers have died, mainly due to the high maternal death rate in the region. The homes also host children who have been abandoned, orphaned or are homeless.

"Sisters and other staff working here are mothers to these children because the infants require a lot of care and attention," Auma said as one of the babies guzzled milk from a bottle. "This is a calling because I have always loved children, even as a little girl. It's a blessing whenever a child is brought here because we are mothers and can care for them."

Sr. Judith Auma, a member of the Little Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi, feeds a baby on Jan. 18 at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Auma, who is also in charge of the home, said the majority of the children at the orphanage were conceived as a result of incest. Others are abandoned in the hospital, primarily by mothers from the neighboring country of Uganda who cross the border to seek health care in Busia.

Some newborn babies living at the home are as a result of their mothers dying due to pregnancy and childbirth complications, Auma said.

"We receive an average of 10 calls daily from people requesting to bring abandoned children or those children born out of incest to this home," she said, noting that sometimes they visit homes to rescue babies who were born out of incest and their parents or relatives want to kill or throw them away. "Most of the requests we receive emanate from health facilities across Busia where people, especially Ugandans, give birth and abandon their children on the hospital bed."

Contributing factors

Authorities from Busia, which is also one of Kenya's 47 counties, said there were rising cases of incest. The government officials said that since 2021, they had reported more than 574 sexual and gender-based violence cases to court, most of the cases being those of incest. The officials noted that hundreds of cases remain unreported due to stigma and threats victims get from relatives.

"We have had fathers defiling their children, and grandfathers defiling their grandchildren," Mary Makokha, the director of the Rural Education and Economic Enhancement Programme based in Busia, told local government officials last year in August during a training on how to tackle gender-based violence in Busia.

"Most of the teenage pregnancies being reported in Busia are as a result of defilement. When incest occurs in Busia and the girl gets pregnant, the child is killed, causing a lot of infanticide, which should be discouraged," she added.

There's widespread teen pregnancy in Busia County; 21% of the county's teenage girls have been pregnant, compared with the national figure of 18%.

As of 2020, the maternal mortality rate in Busia County is 530 deaths in every 100,000 live births, well above the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.1, which aims to reduce maternal mortality worldwide to 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

The United Nations Population Fund notes that teen pregnancy and poor access to maternal health services are the major contributing factors to maternal deaths among young women in Africa. The U.N. agency, which is tasked with improving reproductive and maternal health globally, also reports that girls aged 15-19 are twice as likely to die during childbirth as women 20 years and above.

"Most adolescent mothers here die during pregnancy or childbirth and leave their babies orphans," Auma said, noting that religious sisters are, therefore, forced to become mothers of those children.

Another problem is that most women prefer giving birth at home with the help of midwives rather than going to the hospitals. As a result, some end up dying, and "the babies are brought to us for care," Auma said.

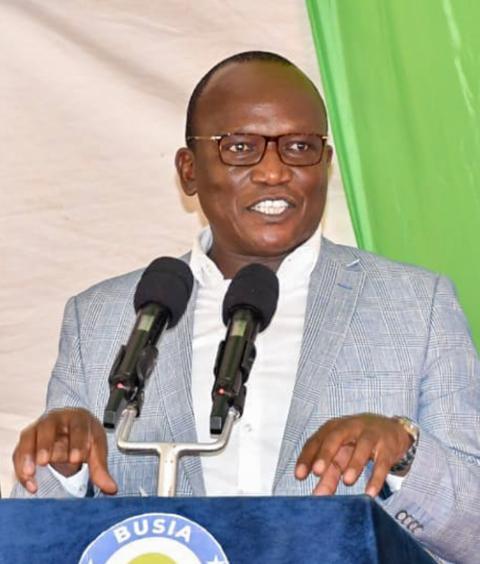

The deputy governor of Busia County, Arthur Papa Odera, acknowledged that most children born out of incest are considered a curse in the community, and they are often killed silently so that the police won't know. In a few cases that are always noticed, he said, those children are rescued and put at various orphanages, including St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home.

"It's always disheartening to hear cases of incest," Odera told Global Sisters Report. "I also don't have specific figures for it because it is not usually reported because of the stigma associated with the incest."

Odera noted that poverty, drug and substance abuse, challenging living conditions, access to pornography, and the collapse of traditional taboos majorly contribute to the prevalence of incest.

"There's a blind trust where parents leave their children with relatives without many questions," he said. "It's time parents become careful not to trust or leave anyone with their children in situations that could expose them to abuse."

Incest victims narrate their ordeal

A GSR investigation unearthed horrific details of several victims in Busia who have been subjected to incest and sexual assault, but they have never reported such cases to the authorities due to stigma and threats from their relatives.

One of the victims who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity said that three years ago her maternal uncle raped her and she became pregnant. Although she gave birth and cares for her baby, she still struggles with the trauma of the attack, and she has never found justice after her relatives threatened her not to report the incident to the police.

The 19-year-old woman said her uncle took advantage of her when her mother left her at his home in 2021 and traveled to Nairobi to seek a job as a housekeeper. One night, she said, her uncle, whose wife was also working in Nairobi, knocked on her bedroom door and "started undressing me, saying he was in love with me and he was going to pay my school fees, and that I should not tell anyone because if I do, he will kill me."

She told her mother and other relatives what had happened, but they never trusted her.

St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"I hate my baby and my uncle who made me pregnant," said the former 12th-grade student, revealing that she was suffering in silence and people were laughing at her. "I am not functioning at all, and I keep on dreaming about the incident. I am in deep pain, but there is nothing I can do to recover and find justice."

Another incest victim confessed that she had to abandon her baby at the Busia County Referral Hospital two years ago after she was raped by her father and she conceived. The 17-year-old girl revealed that her relatives had given her a chilling ultimatum.

"Listen, my daughter, we don't want shame and a curse in this family, and you have no option but to throw that thing [baby] in the bush or kill it," she said her mother told her, hoping she would follow her advice and protect the family from shame.

"I didn't want to participate in the murder of my child," she said. "Therefore, I decided to abandon her in the hospital so that she could be rescued and adopted by someone else."

The sisters noted that many incest victims, which normally occur between father and daughter, suffer from Stockholm syndrome, where they develop irrational empathy for their attackers.

Auma said many lack counseling or mental health services due to the lack of psychologists in the region. Still, as sisters, "we try to counsel some of them to ensure they deal with isolation, denial, incest-related guilt and shame, and to renew their relationships with their children and other family members."

Advertisement

An influx of Ugandan patients

GSR found that hundreds of Ugandans cross the border to Busia to seek treatment due to the scarce health facilities in their country. In December, for example, this publication confirmed from the electronic health records of Busia County Referral Hospital that one-third of patients seeking medical care are from Uganda.

Interviews with several pregnant women from Uganda who had sought treatment at the facility established that many abandon their babies at the hospital because they cannot afford to pay medical bills. They said that hospital services in Kenya are inexpensive compared to their country.

"If you are unable to pay the delivery fee, the maternity hospital will not discharge you," said one of the heavily pregnant women waiting to be attended by a health official. "Majority of women always decide to abandon their babies and escape from the wards instead of being detained like prisoners for weeks or months because of lack of money."

Health officials agreed with their statements, saying the hospital cannot afford to treat patients for free, and in many instances, they are forced to detain them for weeks or even months to press family members and friends to pay up.

"Once these babies have been abandoned at the hospital by the Ugandan women, the police are forced to look for a home for them, and that's the reason they reach out to us," Auma said, adding that they receive such requests daily.

Sr. Judith Auma and one of her staff play with children on Jan. 17 at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya. Religious sisters, with the help of other stakeholders, are caring for abandoned babies, especially those born out of incest, and give them shelter, food, education and a loving home. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"Many babies are also abandoned by women from Uganda who come to work in Kenya as maids and then later on become pregnant and give birth. There was a time when a woman with a grocery shop had to call the police after a young Ugandan girl abandoned her baby at the door of her shop after giving birth."

Battling sexual abuse and incest

Religious sisters and social workers working at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home are focused on ending sexual abuse, incest and rape in Busia and neighboring regions.

Auma noted that violence against women and girls, especially incest, has betrayed the most basic trust between a child and a parent or sibling. She revealed that most victims of incest and sexual abuse had displayed severe distress, such as post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, physical symptoms, suicide attempts and addictive behaviors.

"As a way of fighting sexual abuse and incest, we visit schools, homes, markets and other public gatherings in this region to give talks about sex education," Auma said, stating that they do the visit throughout the year to reach out to more girls and women, parents and elders. "We emphasize sexual purity and the importance of protecting our young girls and women in the community."

She added: "We want to ensure that our girls in the community grow up and achieve their educational dreams rather than being tied down with pregnancies and childbirth."

Sr. Ann Wanjiru, who works with Auma at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home, said parents and protectors have failed to shield children against sexual abuse and incest. She said the sisters were working with the police and regional political leaders to arrest perpetrators of sexual violence.

Sr. Ann Wanjiru, a member of the Little Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi, interacts with children on Jan. 18 at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"We want to raise awareness and seek justice for survivors who have been raped or sexually abused by their fathers, siblings, uncles or other relatives," she said.

Wanjiru lamented that the region has no experts to provide one-to-one counseling to all survivors of childhood sexual abuse, rape and incest.

"As we fight to end these vices, we need to remember the survivors who are suffering from the effects of these abuses," she said. "We need to have professional counselors to help these survivors relieve the physical, mental and spiritual suffering caused by this kind of abuse."

Every child in a family

In the meantime, Auma said the home was working hard to reunite children with their families, adopted or placed in foster care. In the future, she hopes the home can be operated as a temporary rescue center for babies in dire need of care, shelter and support.

"We encourage family care rather than institution care," she said, adding that children brought to the center are allowed to stay until they are at least five years old before they are placed in an alternative form of family care.

Wanjiru explained that institutional care like her center helps children, especially those born out of incest, but it deprives children of a sense of belonging and emotional support that a family setting offers, leading to cognitive and developmental delays. Various research has shown that children growing up in family- and community-based care had better cognitive and physical outcomes and less severe mental health symptoms compared to children who experienced placement disruptions.

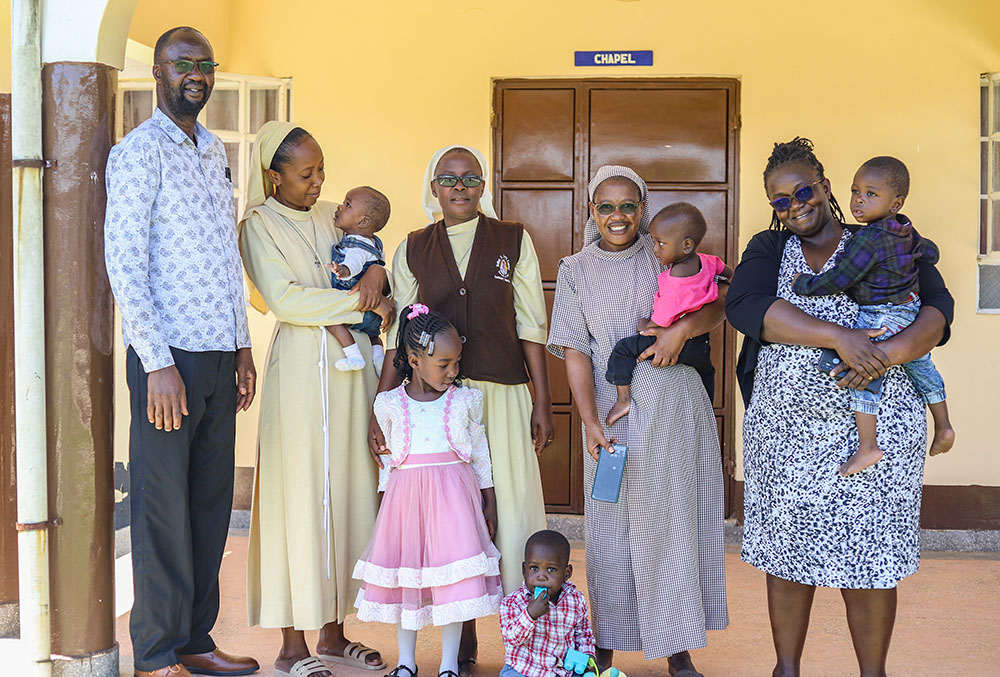

Religious sisters with parents who adopted a child at St. Josephine Bakhita Babies Home in Busia, a town in western Kenya (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"Sometimes the child may be brought to us immediately after the mother dies during childbirth, and the father doesn't know how to take care of the child. In such a case, we take care of the child for a few years and reunite the child with the family," Wanjiru said.

However, she said they provide for alternative care for those born out of incest through adoption, guardianship and foster care placement.

Wanjiru emphasized that, for a child's reintegration to be successful, the sisters plan, prepare and manage well to ensure children are kept safe from harm, including violence, abuse, discrimination and trafficking from their families or from adopting and foster care families.

"After a child has been adopted, we follow up for one year to see the progress of the child before we stop," she said, noting that sometimes they support families with food, clothes and other essential things to ensure children are safe.

"But most importantly, my dream is to see these vices like incest and sex abuse come to an end so that every child that is born can be taken care of by her parent," Wanjiru said.