Street art in Dublin in 2013 protests Ireland's system of adopting the babies of unmarried mothers from mother and baby homes, which were often run by Catholic nuns. The Birth and Information Tracing Bill that is currently proposed in Ireland's legislature follows decades of campaigning for a legal right to birth certificates and family information. (Flickr/William Murphy)

An unusually high number of amendments to a proposed Irish law to provide birth information to people adopted as children appears to reflect wide frustrations that the bill does not go far enough to address the long-term effects of former practices of secrecy at Catholic and other religious-run institutions.

The Birth and Information Tracing Bill that was tabled in the legislature in January follows decades of campaigning for a legal right to birth certificates and family information. The legal changes were recommended by a 2015 to 2021 report into conditions at mother and baby homes, many run by religious orders in Ireland.

The country's system of adopting the babies of unmarried mothers from mother and baby homes came to prominence through the story of Philomena Lee, whose 3-year-old son, Anthony, was sold from Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, County Tipperary, to an American couple. Her quest to find him was published as the book The Lost Child of Philomena Lee in 2009 and the film "Philomena" in 2013.

In what he calls righting a "longstanding historical injustice," Roderic O'Gorman, minister for children, introduced the bill in January to Ireland's legislature, the Oireachtas.

Later in May, O'Gorman issued a formal apology for illegal birth registrations.

This is the latest of several official attempts over the years to change the law for adoptees who, through a lack of official co-operation, were forced to use methods ranging from personal detective work, social media and allowing their DNA to be discovered by others seeking matches.

Lawmakers have tabled some 1,200 amendments to this bill, about a quarter of what the Oireachtas typically sees in a year on all its bills.

Sinn Féin lawmaker and chair of the committee on children Kathleen Funchion described the bill as "very flawed" in an email to NCR. She said the scores of amendments, including expanding the available data pool and providing more detailed information, are necessary "to ensure that all adopted people have unfettered access to their birth information."

Advertisement

Labour Party representative Ivana Bacik told NCR in an email that she and her colleagues "had serious concerns," particularly about a plan to force adoptees seeking information to "undergo a mandatory information session" with a social worker before a birth certificate could be released.

Social Democrat lawmaker Holly Cairns said in a speech that both the state and religious institutions had "denied individuals their identity" and "assaulted their sense of belonging and personhood from the day they were born."

Michael Byrne, 64, a Boston travel agent, was born at St. Mary's mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway in 1957 to an unmarried mother.

He made a Freedom of Information application to the Catholic Charities in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for documentation about his 1961 adoption to an American couple from the Temple Hill orphanage in Dublin. He also left a DNA sample with the genealogy company Ancestry.

Catholic Charities, which had mediated his adoption, gave him almost 10 pages of material "you can't get in Ireland," Byrne told NCR in a telephone interview.

It revealed that his mother was Annie Owens, then 26, and his father a farmer called John Harte. It was only when Ancestry found a DNA match to two half-brothers and two half-sisters in Philadelphia that Byrne discovered that his biological father was Patrick Joyce, who had been in a relationship with Owens.

Left: Michael Byrne, aged 4, at the Temple Hill Orphanage in Dublin in 1961, the summer he left for the United States. Right: The grave in Philadelphia of Bryne’s biological mother, Annie Owens. (Photos courtesy of Michael Byrne)

She had emigrated to America with a cousin at the age of 18 and somehow ended up back in Ireland at the mother and baby home in Tuam.

On a visit to Ireland in 2017, Byrne approached the General Register Office and the Child and Family Agency, or Tusla. They connected him with second cousins in County Mayo who told him Owens had returned to Philadelphia where she died in 2011.

In 2018, Byrne and his adoptive brother Patrick found her unmarked grave and gave her a headstone engraved with shamrocks and the words: "Annie Owens 1931-2001."

When Byrne found a letter from the St. Patrick's Guild thanking his parents for their "generous donation," he realized that money had probably changed hands in his adoption.

After reaching out to Irish adoption groups on Facebook, he was interviewed by journalist Alison O'Reilly for her 2018 book, My Name Is Bridget: The Untold Story of Bridget Dolan and the Tuam Mother and Baby Home.

Byrne plans to visit his newfound Philadelphia siblings in mid-June and says the pictures they have shared show "we look a lot alike, which, for an adoptee, is a very strange feeling."

Despite his own pessimism, Byrne hopes when the law is passed it will not restrict the rights of adoptees to information. "Nothing should be hidden; if it pertains to me or my mother, I should have the right to see it. Period."

Marie Arbuckle gave birth to her son Paul at St. Patrick's Mother and Baby Home in Dublin in 1981. She says she was "coerced" into signing his adoption papers, that she never wanted to leave him.

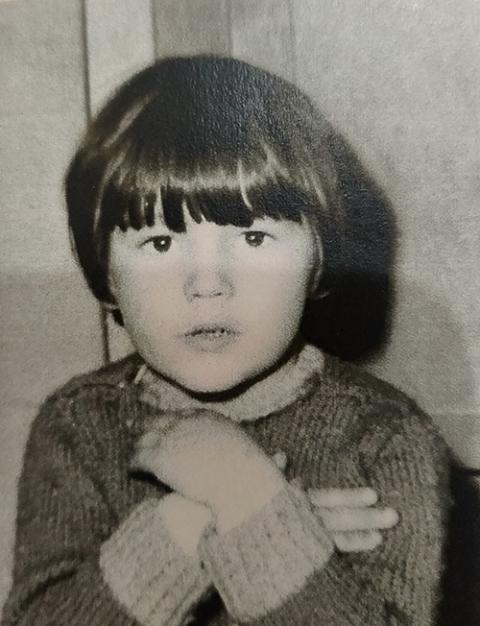

Marie Arbuckle, aged 5 (Courtesy of Marie Arbuckle)

Born in County Derry, Northern Ireland, Arbuckle was brought up in care and sent to a "training school" in County Armagh after a "breakdown" with a foster family. It was there that she discovered her pregnancy and was sent to Dublin.

Despite being born in the Republic of Ireland, Paul was adopted at 1 month old to a family living in Northern Ireland, a neighboring country.

For 15 years, she searched for information but says Tusla claimed her records were destroyed in a fire. It was only in September 2021 after Northern Ireland's mother and baby homes report came out that she was contacted by Judith Gillespie, the chair of the newly created interdepartmental working group on mother and baby homes, Magdalene laundries and historical clerical child abuse.

Suddenly, she was given access to some of her files. "After they were burned in the fire, they were like the phoenix, they rose again, not a scorch mark on the file," she told NCR.

By February 2021, her son was found. Before officials could arrange a meeting, Arbuckle received a private message on Facebook from a woman who turned out to be his partner.

Almost 40 years to the day that he was born, she met her son and granddaughter.

"I sort of blame myself for not being a stronger person back then," she said. "But on the other hand, I blame the state and the church; that we were so stigmatized and made to feel ashamed, that this was a sin."

Emer Quirke was 6 days old when she and her unmarried teenage mother were transferred from Portincula Hospital in Ballinasloe, County Galway, 86 miles away to Sean Ross Abbey in County Tipperary.

She was baptized there and adopted at the age of 9 weeks old.

Her birth was never registered.

It was only after she met her birth mother at the age of 48 that she discovered her adoption had been fraudulent. Someone had falsified her mother's signature.

Emer Quirke with Philomena Lee at a 2015 commemoration event at Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea, County Tipperary, Ireland (Courtesy of Emer Quirke)

"But they still went on and had me adopted on the basis of my baptismal cert [certificate], which is not a legal document," she told NCR in an interview from her home in County Galway. There was also no court order authorizing her adoption.

Quirke found out when she was 9 that she had been adopted. She said she had always felt lonely, noticing how her husband looked like his uncle and his father. Even their two married daughters looked like her husband.

A turning point came one Saturday morning in 2014 after the film "Philomena" had been released. She and her daughter were listening to the radio "and the next thing there was some adopted person speaking." She changed channels. "There was another adopted person speaking."

"Don't think you can hide from this much longer," her daughter said.

Quirke remembered that an elderly aunt had told her, "They went to Tipperary to get you, you know, from the nuns." It turned out to be the same place from which Lee's son was given away.

The chemistry lecturer finally found her birth mother through her own detective work. She tracked her down in 2015 but thought she would try the official channels before approaching her.

The "most horrendous social worker" at Tusla told her, "If we find your mother, we'll write a letter to her and if she doesn't reply to that, we'll write one more letter and if she doesn't reply to that, that'll be an end to it.' "

It turned out that her mother did reply, and the social worker met her. When Quirke asked if she could write to her, she was told her mother needed "counseling."

It was then that she told the social worker she already had her mother's address.

"What kills me is since 1976 in England, you are entitled to your full file. That's what it should be here," Quirke said.