Spirit Catholic Community in Minneapolis blesses children and families baptized on Epiphany in 2023. (Peter Molenda)

Editor's note: According to a 2008 Pew Research study, one of 10 U.S. adults is a former Catholic. Some have moved on to other denominations, others have no church affiliation at all, still others have formed their own communities of former Catholics. In the final three parts of his five-part series, former NCR editor Tom Roberts looks at three different independent Catholic communities — how they came to be, and how they sustain themselves apart from the institutional church.

Do a Google search for Catholic churches in Minneapolis and Spirit Catholic Community shows up on the third swipe at the top of the page, just above the listing for Newman Catholic Ministry. An accompanying map shows it amid a group of red markers denoting mostly conventional Roman Catholic churches.

The page is a visual depiction of a contemporary reality: From a number of angles, what has developed in the Catholic diaspora is indistinguishable from its original home.

A closer look, however, would show Spirit Catholic Community to be anything but conventional, as any unsuspecting out-of-towner visiting on a Sunday morning would quickly realize. Its roots, however, are deep in the Catholic tradition.

It was originally part of a historic parish, St. Stephen's Catholic Church, in Minneapolis. Marilaurice Hemlock, the community life and liturgy coordinator, has a long history of leading Catholic liturgy and music; she has an advanced degree in pastoral studies from Loyola University Chicago, a Jesuit institution. The community celebrates its version of Catholic sacraments, including the Eucharist, which is central to its weekly gatherings.

So it calls itself Catholic, as do others in the diaspora, though it makes clear on its website that it has broken from the Minneapolis-St. Paul Archdiocese.

The recurring question in looking at similar communities that have emerged in the Catholic diaspora is: Where do they fit?

Are they simply outside the fold and thus irrelevant to the Roman Catholic Church? Could they be teaching the institutional church a thing or two? Is it possible that some of their experimentation with the tradition anticipated what synodality is now investigating?

Scholar and author Julie Byrne provides one way of approaching the phenomenon in her book The Other Catholics: Remaking America's Largest Religion, an exploration of independent Catholicism. "My questions started to turn away from assuming anything about Catholicism, and toward discovering how Catholics claim it. I stopped asking if independents are 'really' Catholic. Or, for that matter, if Roman Catholics are. Instead, I just accepted Catholics as Catholics whenever they said they were Catholic."

Spirit Catholic Community in Minneapolis celebrates its version of Catholic sacraments, including the Eucharist, which is central to its weekly gatherings. (Peter Molenda)

That sort of self-identification, she points out, "is a position at odds with 'One True Church' Catholics, who can be found among Roman, Orthodox, Anglican, and independent churches alike."

No matter how one feels about communities that have dropped the modifier "Roman" and exist at varying distances from the institutional church, they've become part of America's religion landscape. And unlike Protestants, for instance, they don't claim to be a different denomination, just a different subset or brand, if you will, of Catholic.

Walking away

In 1990, after more than a decade of leading music and liturgy in Catholic Newman Centers, Hemlock was ready to head in a new direction. "In my mind, I was done, done with the church. It was a complete glass ceiling. I could make lateral moves, but there was nothing else I could do."

So she left her work at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and headed for Minnesota's Twin Cities, where she had good friends. Intent on finding a new career, she went through seemingly endless rounds of applications and interviews, eventually picking up part-time work in sales, as a teacher aide, and as a substitute teacher. But nothing permanent.

And one Sunday she headed to St. Stephen's Church, hoping to run into an old friend, a Jesuit she knew who often visited the parish. They did run into each other at Communion time, and he quickly mentioned that the parish had just lost its liturgist and he thought she should apply.

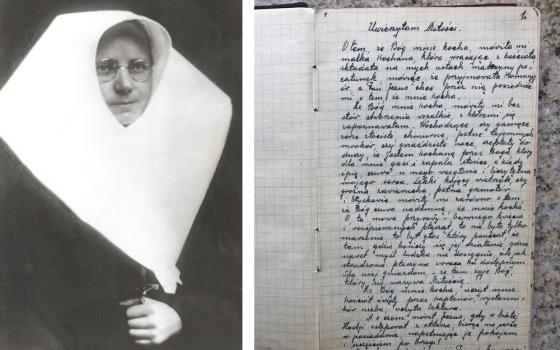

Marilaurice Hemlock leads the Litany of the Faithful during the 2023 Easter Vigil at Spirit Catholic Community in Minneapolis. (Ruth Cioni)

She was attracted that first visit to the way the parish conducted liturgy, to the obvious commitment to social justice and its expansive ministry, which included a homeless shelter right next to the church.

She applied, and her undergraduate degree in music and her master's in pastoral studies apparently was the right fit. She was hired and went to work there in July 1991 as director of liturgy and music. She remained in that position until 2008, when the leadership of the archdiocese and the parish changed.

The retiring archbishop, Harry Flynn, she said, "loved St. Stephen's. He loved that we had a shelter; he loved that we had a free store for clothing, he loved that we were doing job education and computer skills and all of these pieces."

Though he received some complaints from time to time, she said, he also apparently ignored those about certain practices, including women reading the Gospel and preaching, that pushed liturgical limits. Especially the liturgies that were held in the school gym, where there was what she called an "open pulpit" and where women preached and where a "strong prayer leader group evolved."

But a new archbishop was on the way, and a newly assigned pastor presented what some took as a list of ultimatums that included "only the ordained would be permitted to open the word and preach, and all liturgies would occur in the church proper and not in the gym," Hemlock said.

Flynn called a meeting of parish staff and parish council, including Hemlock. "He gave us four weeks to get our act together," she said.

What followed were "meetings upon meetings upon meetings" with people whom she described as both grieving and angry. She said the community included people skilled in dealing with groups in such situations.

Advertisement

Ultimately, she said, "people could see for themselves. They came to St. Stephen's to fill up from the well. They got filled up and off they went into the world to be head of the Women Against Military Madness, to head the Pax Christi group, to be active and have a great presence in Veterans for Peace," among other endeavors.

"They determined that without the prayer of Sunday, they could not do their work. They could not go out and be about the Gospel without that strength." And without the liturgies in the gym, that wouldn't be possible.

Eventually, they decided to move, renting space in a nearby converted mansion, a space within walking distance. One Sunday morning in March 2008, the group gathered up a few belongings, as well as "the book and the cross" and marched, singing "In the Light of God" to the new location.

Becoming an independent eucharistic community

If the attachment to the best of Catholic tradition remains a strong influence for many in the diaspora, the worst of the institution's history, especially the most recent, is also unavoidable. For Mary Condon Peters, one of the founding members of Spirit Catholic Community, the name became a problem.

Because of that, she says of herself today, "I am not a consistent member" even though she loves the community, loves being in the worship space with others and says of community members, "They're important people in my life."

Spirit Catholic Community gathers in a previous worship space in Minneapolis. The community has moved three times since exiting St. Stephen's Parish. (Peter Molenda)

"I just think having the name Catholic on such a wonderful community tarnishes it," she said in a recent interview. "But I do go frequently, and I stay in communication with community members, and I support them, and I get their communications, which keeps me connected spiritually as well as with the community.

"I think when people hear the word Catholic, it goes to a certain place. It goes to guilt, and shame, and patriarchy."

She is especially critical of the church's lack of welcome for women and members of the LGBTQ+ community and of the church's lack of accountability for the sex abuse scandal.

A lifelong Catholic and former Sunday school teacher at St. Stephen's Parish, as well as a member of the parish council and the parish development council, she says that at age 66 she's not looking back. "The time is up for the traditional Catholic church."

She also knows that the community will retain the name "because they do hold true to the tradition, that's very important. And they don't want the church to be able to take that from them."

Holding true to the tradition doesn't mean mere imitation. For starters, and unlike other independent eucharistic communities, there is no ordained person who leads services and sacraments. That's intentional.

Hemlock said some people left early on because they wanted a priest involved. "I'm not ordained," she said. "That's a fine line there. The community calls me to do this, to anoint them when they're dying. But there's no formal ordination."

The issue came up, she said. "We talked about it. We talk about everything. And people said we don't need that person who puts on something special, who has letters after their name. So, we claim our baptism as baptized priest, prophet, and we say liberator instead of king. We are baptized as priests and we claim that."

The practical implications are significant. Instead of one person leading the eucharistic prayer, for instance, everyone says the words of institution.

What about reconciliation? "It's lovely," she said. "It is always communal." The room is arranged so that members are facing each other, and just as all say the words of the eucharistic prayer at Mass, everyone says the words of absolution.

But first there is a meditation "on the Gospel account of the woman caught in adultery — of course there are many questions about that, but the part we use it for is Jesus writing in the sand," she said. "So we have a big tray of sand. We invite people to come up with a symbol of what they are wishing to give over, or what they are asking forgiveness for, and then we say the words of absolution and we erase, and the sand is made smooth again."

Multiple beginnings

It is one thing to claim connection to a tradition, quite another to do it without a connection to the traditional structure and its considerable resources. If roaming is appropriate for a diaspora people, the Spirit Catholic Community has done its share. It has moved three times since exiting St. Stephen's Parish.

The latest move, which holds potential for innovation that goes beyond the Spirit Catholic Community, occurred in 2021 to a renovated space and a partnership called "New Branches."

The space, originally inhabited by Lake Nokomis Lutheran Church, is now also home to Living Table United Church of Christ and Spirit Catholic Community.

"At a time when thousands of churches across the country are closing every year amid shrinking membership and growing expenses, these congregations have reimagined their church as an abundant resource to share instead of a financial burden," wrote the Minneapolis Star Tribune in a feature story about the arrangement.

Spirit Catholic Community moved in 2021 to a renovated space and a partnership called "New Branches" with Lake Nokomis Lutheran Church and Living Table United Church of Christ. (Peter Molenda)

The three churches "now have a tax-exempt building partnership, with shared ownership, shared costs and a shared hope for a more secure future."

Life together, or at least shared, has its challenges, and the greatest one, said Hemlock, is faced in ongoing negotiations about scheduling, something made more difficult because, unlike Lutherans and UCCs (and unlike most ordinary Catholic services), those of Spirit Catholic Community can sometimes go for an hour and a half.

But the Lutheran pastor, Sara Spohr, sees in the arrangement a model with far-reaching implications. Reflecting on how Christianity has split over centuries, she told a publication of the Lutheran Minneapolis Area Synod, "I believe that the next Reformation is going to put that puzzle back together again. This will happen, one group at a time, or in our case three!"

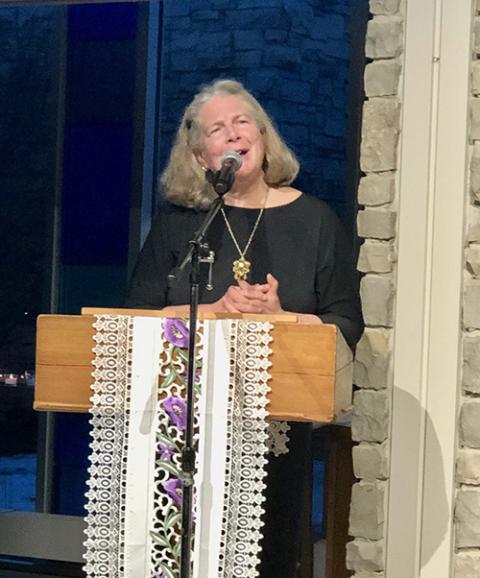

Asked if she believes the time will come when independent eucharistic communities like Spirit Catholic Community might reunite with the institutional church, Hemlock replied, "I believe it would be beneficial for both parties if we all were under one tent. I do not see it happening."

While the community often refers to Catholic theologians and major figures in the church such as St. Archbishop Óscar Romero, and has even read from the U.S. bishops' pastoral on peace, she believes the church's intransigence over women, treatment of the LGBTQ+ community and exclusion of certain people from the Eucharist will remain barriers to a reunion for the foreseeable future.