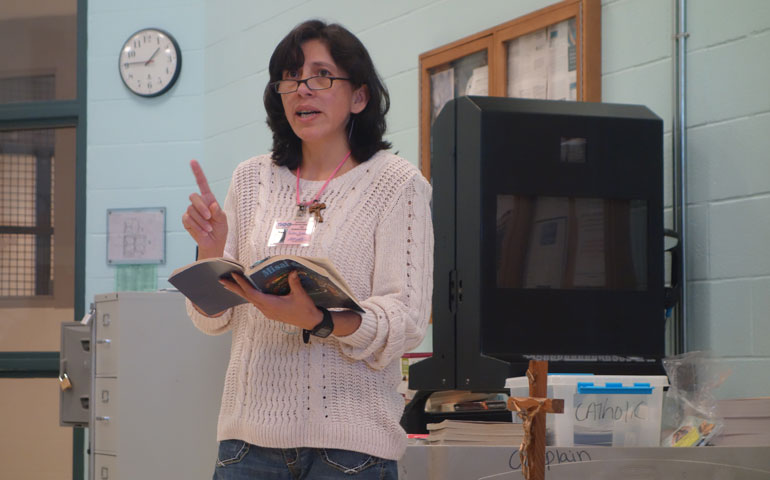

Esmeralda Saltos communicates a message of Christ-centered hope, mercy and love to 86 detainees during the first of three Sunday Catholic services at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash., Sept. 13. (Photos by Maria Laughlin)

For Esmeralda Saltos, a typical Sunday includes four worship services: morning Mass with her family at Holy Disciples Parish in Puyallup, Wash., and then three back-to-back afternoon services that she organizes and leads at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma.

Saltos arrives at least 30 minutes before the first afternoon service is set to begin, carrying a Bible, holy water and Communion -- the few items that the GEO Group, the global for-profit prison company that runs the detention center, allows her to bring into the facility.

Making her way through throngs of mostly Latino families who have lined up to visit with loved ones (meetings are face-to-face but separated by Plexiglas and the use of a telephone), she requests a key to a locker at the check-in desk to stow her other belongings. She exchanges her driver's license for a badge displaying her name, photograph and the GEO Group logo.

Saltos isn't an employee, but, as an approved volunteer coordinator with the facility's chaplaincy program, she does work closely with GEO employees and in accordance with GEO policies and procedures in order to be consistently present to those she serves. Hundreds of Catholic men and women -- as well as non-Catholic detainees who choose to attend Catholic services -- are currently held at the Northwest Detention Center while awaiting administrative proceedings that will, at some point in the near or distant future, result in either deportation or release.

Saltos' ministry has also been shaped by guidelines established by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the federal agency that contracts with GEO Group and is tasked with ensuring, among other things, that immigrants retain their constitutional rights while in detention, including freedom of religion.

On a recent Sunday, this NCR reporter joined Saltos and her small team of pre-verified, trained volunteers. When they receive final permission, they cross through the first of up to seven secured doors that will lead them to an unoccupied pod that they will convert into a sacred worship space before the first grouping of 86 attendees arrive.

The number of attendees range from 70 to 100 people at each of the five Catholic services that are held for male detainees every week, in addition to a smaller service for female detainees on Tuesday evenings.

Accompanied by security personnel and Chaplain Keith Henderson, who is employed by the GEO Group, volunteers work quickly to unload the rolling altar cart, hang posters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Our Lady of Guadalupe with Velcro tape onto a message board, and stack boxes of donated Catholic Bibles and prayer books. A table is soon set with an altar cloth and a small standing crucifix.

Access to Catholic Bibles and other articles of faith, such as rosaries and prayer books, remain an impassioned priority for Saltos. Such donations occur only once every few months, she estimated, so this service will end with an excited, Christmas-like buzz as the mostly young men line up to receive their own Bible, sometimes for the first time.

"We suggest that they hand in their Bible rather than take it with them when they leave, but they almost always take it with them," Saltos said. "There's a constant need."

She has seen the profound impact these materials can have on individuals as well as on the community, not only helping detainees learn more about their faith but even inspiring some to hold daily Bible studies and sing hymns together.

"When I'm here, I see more need for God," one male detainee said. "Since I came here, I've felt empty. I needed something, but I didn't know what it was. Then my roommate gave me a Bible, and this got my attention. I used a rosary for the first time as well. I began to feel that I could fill this emptiness with Jesus in my heart. ... We all have a gift from God; we just need to build on it. Whatever I know, you know it, too. It's as easy as knowing how to express yourself."

Saltos is the designated pastoral minister to the Catholic population at the Northwest Detention Center, a position funded by Seattle Archbishop Peter Sartain in 2014. According to the director for pastoral care, Erica Cohen Moore, the archdiocese will continue to "be creative in finding funding resources to make sure the ministry continues."

On this particular Sunday, Saltos wears a simple white sweater and jeans, and a rustic wooden cross hangs from a piece of white yarn knotted around her neck. As detainees begin to file in, some pause to kneel on the concrete floor before the image of Jesus crucified, their heads bowed and shoulders bent, faces turned away in a private moment of silent prayer. Others greet the volunteers with a brief nod and smile or handshake before choosing a seat among rows of plastic chairs.

After singing together and listening intently to the Scripture readings (read by two detainee volunteers), Saltos begins her message.

"Brothers, in the first reading of the Prophet Isaiah, we learn of what our Savior will have to go through for love of us when Jesus offered his back and his cheek to those who were beating him and did not turn his face from those who were insulting and spitting on him, [yet still had] the assurance that the Lord will not abandon him and will help him to not be confused or ashamed. If Jesus had to go through this without deserving it and only for love, it shows us that we need to reflect on his passion so that we can face our tribulations with confidence, knowing that our Lord does not abandon us."

Later, in a gently buoyant voice, Saltos describes her time with detainees as joyful and full of grace, despite the fact that interactions, by their nature, occur within a decidedly prisonlike environment. Yet Saltos returns week after week, eager to share God's word.

"What makes Esmeralda a real treasure is that she has such a strong faith in God and her church and a huge heart for the work that she does," former chaplain Lonnie Scott explained from his home near Spokane, where he now serves as a pastor at a local church. "That faith, coupled with a huge heart, makes her what she is."

He continued, "You can have detainees who have gone through horrible experiences. Through faith, they experience a spiritual healing and the rest of the healing follows. I saw this over and over again ... how fellowshipping could overcome the mental stresses of incarceration and so many other obstacles."

For Saltos, outreach to those experiencing present trials and future unknowns is also rooted in past experiences and challenges, including a fondly remembered childhood in central Mexico forever altered by her father's murder and, later, her family's decision to move to the United States.

She spent part of her teenage years growing up in the homes of kindly relatives (she remembers her mother and her aunt cooking meals for 19 children at a time) and, during young adulthood, made choices out of "stubbornness and pride" that led to two unplanned pregnancies and single parenthood.

Now married to Pedro and with five children, Saltos has come to feel that her outreach to immigrants also brings a mother's presence into an environment lacking direct ties to the institution of the family. Careful to maintain proper boundaries that respect her own and others' privacy, she nonetheless possesses a distinct warmth and confidence that "throws off sparks," as one volunteer described her energy and bright, engaging presence.

Her mother's prayers and the seed of faith planted in her heart at a young age have served as a compass of sorts, guiding her toward the knowledge that "I had to do the right thing" and follow "that call in my heart."

Indeed, such aspects of her own story have both stretched and deepened her ability to feel others' inmost struggles and reflect back to them their sometimes unrealized potential. She knows, she said, "what it's like to fail and then get up and let God use us in a way that's fruitful."

Her ongoing ministry to detainees, paired with the joys and support found within marriage, her family, and her larger community of faith, have become their own answers to this long-ago call to be productive, faithful and a bearer of mercy. Even at home, whether harvesting vegetables in her beloved garden or responding to her family's needs, she remains mindful of her responsibilities at the Northwest Detention Center, and her ongoing work among people who are largely forgotten.

"I always wanted to visit detainees as a work of mercy, which is something that my mother often talked to me about when I was a young girl, but I didn't know where to start," she said, her voice touched with gratitude and humility. "This desire was granted in a much bigger way than I'd hoped for."

[Julie Gunter is a frequent contributor to NCR.]