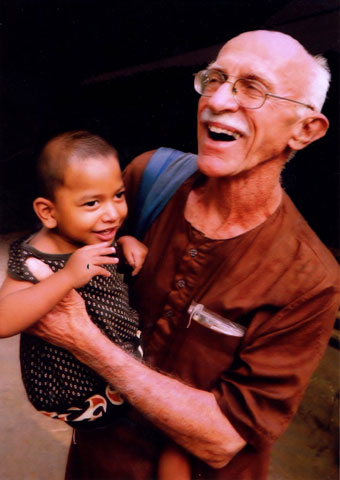

Maryknoll Fr. Bob McCahill with a young friend in Bangladesh in 2012

For many years, Maryknoll Fr. Bob McCahill has been sending an annual letter to NCR and other friends at Christmastime, chronicling his experience living among the people of Bangladesh. Following is an edited version of his 2012 letter.

Dear Friends,

As I sat reading in the doorway of my hut, a neighbor carried Meeteela to see me. I stopped reading in order to elicit a smile from the year-old girl whom everybody likes to tote around. Instead of smiling, however, Meeteela pulled back from me. This is not like her, thought I. Her guardian informed me about Meeteela's fear: "The spectacles you are wearing scare her." (In this neighborhood I alone wear eyeglasses.) I removed the specs from my face, and the cap from my head besides. The accessories having been removed, she rewarded me with a smile of her own. The best things in life are free.

Outside the town's post office on a chilly morning, two teenaged girls wearing face and body-length veils stepped into my path. Even though it is a public place, they had the daring to initiate a conversation. Their religious guides caution girls not to behave so boldly. But these are Bengali Muslims, spontaneously sociable. The lasses' faces were mostly covered, but laughing eyes revealed they were delighted by our meeting. They told me they had once seen me bicycling in their far distant village. They simply wanted me to know they recognized me.

Kookee, a disabled, middle-aged woman who begs door-to-door to support herself and her mother, was newly returned from making her daily rounds. She sat in the corner tea stall of our bazaar counting the coins people had given her. Counting was difficult; her eyes are bad. Finally she finished. Her day's income amounted to 16 takas (20 cents). Then Kookee treated herself to a cup of tea -- poured into a saucer to make it easier to soak a small piece of hardened bread. It was both her breakfast and a reward for successful Friday morning begging. Her livelihood depends on one of the five pillars of Islam: almsgiving.

In the village of Shingbasha, a wind and rain storm struck with force, prompting me to knock urgently on a farmer's door to request shelter for myself and my bicycle. The storm passed in 30 minutes, so I resumed my journey. Minutes later, on another path, a farmer frantically signaled me to avoid a power line brought low by the storm. I swerved in the nick of time. The elated look on my benefactor's face expressed what he did not say: The reason I am so happy is I just did something gallant. I saved you.

We were in our assigned seats on the fast-moving Ekota Express train when it made an unscheduled stop to take on military personnel. The entire 70-seater railcar was swiftly evacuated to make space for the soldiers, except for the four of us: Ashraf, age 6, released that day from a hospital, and his grandmother, uncle and me. Although a soldier browbeat me to leave, I declined, and beseeched my companions to stay put. Later on, the officer in charge of the soldiers invited me to sit with him. Major Naim, a former U.N. peacekeeper in Sudan, was born in 1976. I came to Bangladesh in 1975. Bengalis respect age and I had seniority.

While visiting the home of Ain Addin, he complained to me of weakness. Ain is diabetic so I urged him to do the exercises that will help control his condition. "I do exercise!" Ain protested.

I know the man not to be the energetic type and was skeptical of his claim. "What exercises do you do?" I inquired.

"I do my prayers five times daily!" Ritual prayer requires standing, bowing, prostrating, and sitting on one's legs and ankles. It is exercise, true, but maybe not the kind needed to impede diabetes.

One afternoon, friendly store owner Probir greeted me warmly and clarified for me the reason for the long red paste mark down the center of his forehead. He spoke of Krishna and that Hindu god's relevance for his life. We both rejoice in the freedom we share to speak of what and who is meaningful to us. Probir was not preaching to me. He was facilitating me, sharing with me the encouragement he feels from his faith. Won't it be splendid when we all -- Muslims, Hindus, Christians, all -- can speak and listen to others explain what inspires us without quarreling about it?

Shaheen had recently returned from a month away in Saudi Arabia, on pilgrimage. "How was the experience?" I asked. Shaheen spoke of the hundreds of thousands of Muslims in one place, of the heat at noonday when pilgrims left their air-conditioned rooms to go for prayer, and of eating camel meat. "Are you glad you went?" I asked.

"Definitely!" my businessman friend exclaimed.

"Did you make any resolutions there, such as to read the Quran more regularly?" I queried.

"No," he easily admitted, for the pilgrimage is not a retreat but rather a duty. Having fulfilled that duty, Shaheen feels spiritual security.

Early in the morning, I bicycled to Chawk Darap village through intermittent rainfall. There I wished to notify Sumi and Tara, her auntie, of our impending trip to the hospital. At their broken-down, mud-walled home, Sumi and her family came out to meet me. They were embarrassed not to have any food to offer me -- especially because it was the week of their grandest Islamic festival, Eid al-Fitr. Eid is a time of heightened hospitality that, in Bangladesh, always involves food. Their inability to place a snack in front of me assures me how favored I am by God to be able to serve truly needy families. Indeed, the best things in life are free.

Fraternally,

Bob