Milagros Orengo, second from left, her daughter Emily Orengo, and Maria Santos, right, all from Egg Harbor, N.J. pray behind a barricade at Independence Mall in Philadelphia, as a Mass with Pope Francis at the Cathedral Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul is projected on a large screen, Saturday, Sept. 26, 2015. (RNS/AP/Carolyn Kaster)

Emmanuel Perez was about 15 years old when he decided the Catholic faith was not for him.

Perez's cousin had just died in a car crash and his mother drove from her Santa Ana home in Orange County to Tulare near Fresno to help prepare the body for the viewing. She wanted to "be there for her in her last moments," said Perez, 23.

His mother, however, was forbidden from getting close to the body.

Because his mom had divorced his father and lived with her new partner without getting married, Perez's aunt didn't consider her "holy enough" to be near her niece's body. Perez said it was heartbreaking, especially because his mother devoted herself to the Catholic faith to create a bond with her family while his dad was not around.

That's when he realized: "This is not for me. This is not what I believe in."

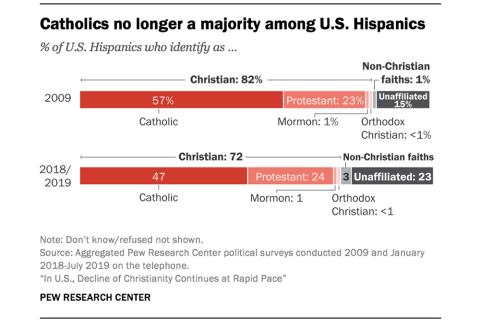

Perez is part of a religion shift where Latinos in the United States are no longer majority-Catholic, according to a new Pew Research Center survey released Oct. 17.

In 2018-19, 47% of Latinos identified as Catholic, down from 57% a decade ago.

The study found the share of Latinos who say they are religiously unaffiliated is now 23%, up from 15% in 2009.

The report, a collection of yearly political surveys asking about religion, highlighted a continuing decline of Christianity in the U.S. It found that 65% of Americans describe themselves as Christians, down from 77% in 2009.

Jennifer Hughes, a University of California Riverside associate professor who focuses on the history of Latin American and Latino religions, said that although this is a major shift, it's important to consider the nuances of Latino Catholic identity.

"Because to say you're Catholic … if you claim that, it may mean you go to church every Sunday and you go to confession and you're in good standing," Hughes said. "Those people who say they're not Catholic, they could still be culturally Catholic.

"I bet you a lot of those people who are saying, 'I'm no longer Catholic,' if you go in their house you may see a little Virgin Mary on their altar."

To Hughes, anyone who participates in the life of the church, whether it's in church or through saints and altars in their home, "I would say is Catholic." Hughes outlined a number of reasons why some Catholics are critical of the church, including the clergy sexual abuse scandal and the rule that women can't be priests.

Catholics no longer a majority among U.S. Hispanics (Graphics/Pew Research Center)

"Those things are starting to wear away of support," she said.

Pope Francis has sought to make the Catholic Church more inclusive. In 2015, he issued a call to the church to embrace Catholics who have divorced and remarried. This September, he met with American Jesuit priest James Martin at the Vatican to discuss LGBTQ Catholics — a move some saw as support for a priest who's called on Catholics to be more compassionate to LGBTQ people.

Still, for some former Latina Catholics, that's not enough.

Over the years, Greta Hernandez, a 34-year-old Nicaraguan American from Los Angeles, has become more disillusioned with the Catholic Church.

She disagrees with the church mandates of waiting until marriage to have sex and the lack of LGBTQ inclusivity. She also didn't understand why priests seemed to be held to a higher regard than nuns. Additionally, even though she was baptized and celebrated her First Communion and confirmation, she never fully identified as Catholic.

"I never really felt comfortable going to Catholic Mass. I felt like I just went to warm a seat. I really didn't understand what the priest was saying as a child," Hernandez said.

She yearned for a sense of community.

Now, Hernandez is exploring "what it means to be a Christian woman." She said most of her family is now Protestant or evangelical, while her mom remains Catholic. Hernandez started attending a Foursquare church in Los Angeles near her home. She enjoys the worship services, where the message is relatable through music. She said the church is liberal on social issues.

"The message is clear. I can understand it and adapt it to my modern life," Hernandez said.

Harold Morales, a professor at Morgan State University in Baltimore whose research focuses on the intersections between race and religion, was taken aback by the new Pew findings.

"Even as people were leaving the Catholic Church, those numbers were being replenished," Morales said. "To see this decline by almost 10% in the Latinx Catholic population, was surprising."

Morales, along with two other researchers, surveyed 560 Latino Muslims across the U.S. in 2014 to better understand Latinos' conversion to Islam.

Among Latino Muslims in the 2014 survey, the researchers found that a 56% had converted to Islam from Roman Catholicism. Morales noted some Latino Muslims found a sense of community in Islam that they did not find in Catholicism. Others said they liked accessing their spirituality without the mediation of a priest, Morales said.

Greta Hernandez, 34, was raised Catholic but no longer identifies with the faith. Photographed Thursday, Nov. 7, 2019, in Los Angeles. (RNS/Alejandra Molina)

"There's a lot of people who talked about the (Muslim) prayer giving them a sense of peace that they didn't find in other places," Morales said.

Although the percentage of Latinos who identify as Catholic has declined, Latino Catholics remain a significant demographic in the church. Almost four in 10 (37%) are Latino, according to Pew Research's 2019 report.

Fernando Romero Orozco, 36, is a practicing Catholic who understands how that lack of community in the church can lead some to leave the faith.

"We just go to Mass and call it a day and come back next Sunday, but there isn't that connection after Mass is over," said Romero Orozco, who lives in Upland in San Bernardino County.

Romero Orozco is an executive director of a day laborer center in Pomona. At the center, an image of Santo Toribio — a Catholic saint believed to watch over immigrants — hangs on a wall. Outside, an altar of the Virgin Mary is erected inside a tiny house the laborers built.

Romero Orozco' Mexican identity is deeply linked to his Catholic faith. He supports abortion rights and same-sex marriage. He said learning about Catholic theology, including the first- and second-century writings about Jesus, has helped him remain rooted in the faith.

Despite the church's rhetoric surrounding same-sex marriage and abortion, he said he's able to "put that aside and still be able to feel a connection to the church."

Romero Orozco said he appreciates Pope Francis' push for inclusivity, but "it has to trickle down to our priests that we go on Sunday."

For Perez, there are some traditions linked to the Catholic faith that he cherishes. He enjoyed celebrating Día de los Muertos by setting up an altar with candles and flowers as a way to honor his grandmother.

Perez said his mom remains Catholic, and as for himself, he doesn't identify with any religion.

"I focus more on just being positive," he said.

Advertisement