A young woman helps sanitize pews following a memorial Mass in English and Spanish on March 13 for parishioners who have died from COVID-19 at St. John-Visitation Church in the Bronx borough of New York. Many members of the parish community were infected by the coronavirus, including more than 50 who succumbed to it. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Editor's note: This column reflects an e-mail conversation between theologian Miguel Díaz and Dr. Maximo Brito, a Chicago physician who specializes in infectious diseases. Brito is professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the chief of infectious diseases at Jesse Brown VA Medical Center. During this pandemic, digital media has become an increasingly necessary means of maintaining and cultivating daily relationships. In this exchange, Brito's contributions appear in italics. The idea of an e-mail dialogue as a form of Latin@ literary expression was explored by the editors of Lengua Fresca: Latinos Writing on the Edge (2006).

Dear Max,

The impact on Latin@s of COVID-19, social distancing, and vaccination hesitancy and accessibility has been on my mind lately. As Latinos, we both know that this has been a very difficult year for all of us. Social distancing for anyone is hard; social distancing for Latinx persons is quite challenging, given our cultural emphasis on the importance of family and sustaining relationships. Beyond having to cope with the detrimental effects of social distancing — psychologically, physically, and socially — Latinx bodies have also been disproportionately affected by this pandemic.

I have been reading some studies that highlight ethnic and racial inequalities associated with COVID-19. Systemic racism plays a role in making Latinx bodies more vulnerable to infection, and when infected, Hispanics experience mortality at rates double that of white Americans. From your work in Chicago as a Latino physician and an expert in infectious diseases, can you help me put this troubling news in perspective?

Dear Miguel,

As you indicate, the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 epidemic in Latinx communities is likely multifactorial and is influenced by cultural, sociodemographic factors and other social determinants of health. The convergence of some of these factors makes our community more susceptible to the spread of a respiratory pathogen such as coronavirus. Here are some reasons to explain the higher risk of COVID-19 in our community:

First, a substantial number of Latinx households are multigenerational. According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 27% of Latinxs live in homes with at least two adult generations (i.e., grandparents, parents and grandchildren). This living arrangement increases the probability that a younger, more mobile, person who works outside the home becomes infected with the coronavirus and passes it to an older individual who is more susceptible to COVID-19 complications and death.

Advertisement

Second, many Latinxs work in service, transportation and construction jobs for which working remotely is not an option. These workers have more of the sorts of person-to-person interactions that facilitate the transmission of coronavirus.

Third, the Department of Health and Human Services reports that Latinxs have the highest uninsured rate of any racial or ethnic group in the United States. The lack of health insurance results in poor access to health care services and a higher frequency of conditions like obesity, diabetes and hypertension, which provisionally appear to increase the severity of COVID-19 infection.

With increased numbers of vaccines available now across the nation, how are our Latinx communities doing when it comes to getting vaccinated? I recently heard some doctors expressing concerns about decreases in the national rate of vaccinations. According to the most recent CDC data, 44 % of the U.S. population has received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Skepticism about the vaccine is high despite the devastation COVID-19 has caused in the Latinx community. For example, in Chicago Latinxs account for 30% of all cases and 30% of all COVID-19 related deaths in the city. However, the Chicago Department of Public Health estimates that only 25% of Latinxs have completed the COVID-19 vaccine series compared to 39% of the White population. Although Latinx vaccine hesitancy is rooted in the same sources of disinformation and anti-vaccine sentiments pervading other communities, fear among undocumented individuals of being identified by law enforcement constitutes a distinctive barrier in our community.

This week, I participated as a member of the Ambassadors Circle in a National Democratic Institute event hosted by Secretary Madeleine Albright highlighting women's empowerment. Secretary Albright honored Stacey Abrams as one of our national and global leaders fighting on behalf of democracy and human rights.

During this event, Abrams addressed the challenges that brown and black bodies face with respect to the pandemic and how they trail behind white populations in vaccinations. She noted that among the challenges is a lack of easy access to vaccination centers, a problem exacerbated by an inability to get to these centers because of distance as well as inadequate means of transportation. Apparently, in some locales this is further complicated by insufficient or even unreliable information.

The Biden administration strives to vaccinate 70% of the population by the Fourth of July. Their efforts include increasing options for walk-in appointments, offering more pop-up clinics, and sending out mobile units — in other words taking vaccines to the barrios!

While these initiatives are helpful, as you well know, communicating effectively with Latinx communities is not just about conveying the most accurate information. How vaccine info is conveyed and above all, who conveys it are key to securing cooperation. I think about the power of our elders, especially the abuelitas, our grandmothers, to inspire good behavior. Wouldn't it be great, for example, to start a campaign with hashtags like #AbuelaDiceVacunate! and #AbuelaSaysVaccinate! in order to spread the word on social media with the help of our tech-savvy Latinx young people?

One such culturally relevant initiative was launched by Salud America!, a national Latino health equity organization based at the Institute for Health Promotion Research at UT Health San Antonio. They created a multimedia intergenerational campaign called #JuntosStopCovid targeting Latinos and Latinas. Their bilingual resources include helpful fact sheets, infographics and an active social media presence on platforms like Twitter.

In general, Miguel, people of color encounter challenges to access the health care system. Notable obstacles for the Latinx community, in particular, include lack of insurance coverage, poverty, undocumented immigration status, language barriers, and a lack of culturally appropriate resources to help individuals navigate a very complex health care enterprise. As a health intervention, COVID-19 vaccinations are viewed through a prism of challenges that some may find unsurmountable. In addition to these challenges, we must confront issues of mistrust and rampant disinformation.

Thus, the success of vaccination campaigns will depend on our collective ability to make the process simpler, recognizing that black and brown people's wariness toward clinical research and new therapeutic interventions is rooted in very real past unethical and racist practices.

We need to meet people, figuratively and literally, where they are. We have to spend time and effort reassuring people that the speed of development and rollout of these vaccines was achieved by an unprecedented commitment of human and financial resources, which is unlike any other research endeavor in recent history. We must show empathy, acknowledge the origins of people's mistrust, and ask questions to understand the reason for a person's vaccine refusal.

In addition to the strategies the current administration is implementing to streamline vaccine programs, we need intensive community outreach within Latinx neighborhoods to engender trust and convey the benefits of vaccination. As an example of a successful community-based health care program, our University of Illinois Community Clinic Network, runs storefront, inconspicuous clinics in resource constrained neighborhoods throughout Chicago. We have proven that our model for caring for socioeconomically marginalized persons is successful at addressing racial inequities and bringing disenfranchised people of color to care.

Lastly, as you have already mentioned, the messenger is sometimes as important as the message itself. Individual or small group interactions between trusted figures and community members will be key to persuade Latinxs to get the vaccine. Religious leaders, clergy, and other people of faith are very important in this effort. Recent reports indicate that vaccine hesitancy exists in some Christian communities, therefore, trusted leaders who help deliver the message of vaccine efficacy and safety are essential for community acceptance and broad vaccine coverage.

I am counting on you as a man of faith, a scholar, and teacher of theology to help us further the cause!

Abrazo,

Max

Muchisimas gracias, Max, for elaborating on the challenges that Latinx communities face in addressing COVID-19, as well as offering even more effective strategies that can be adopted to increase vaccinations. I want to pick up on the last point you made related to vaccine hesitancy in some Christian communities.

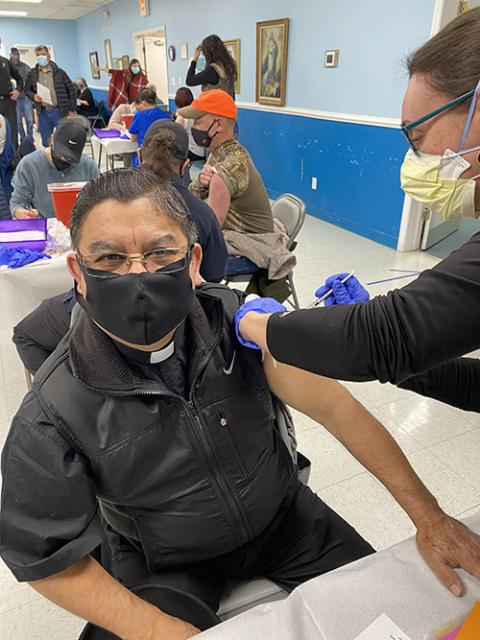

Fr. Gabriel Carvajal Salazar get his COVID-19 vaccine at Our Lady of the Highways Church in Thomasville, North Carolina, March 6. (CNS/Catholic News Herald/Joe Thornton)

Faith and religious leaders play an influential role in addressing this health crisis. There is no doubt that those who minister among Latinx people have a moral obligation at this time to interpret Christ's commandment to love our neighbors in light of this public health crisis taxing our communities.

Speaking from an evangelical perspective, the Rev. Gabriel Salguero, president of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition, described partnering with the Ad Council in order to produce public service announcements in Spanish for faith leaders focused on the positive and life-saving benefits of COVID-19 vaccines. Salguero indicated the significance of framing the message around theological concepts familiar to Christians, like the Good Samaritan, in order to communicate that "taking the vaccine is part of this moral commitment of loving your neighbor and loving your community."

For Catholics, Pope Francis has taken the lead, emphatically stating, "ethically everyone should get vaccinated," because it impacts both my life and the lives of others. He has called us to embrace a "contagion of hope" to overcome "indifference, self-centeredness, division and forgetfulness" that plague our world, especially when it comes to disparities related to COVID-19.

I am grateful for medical professionals like you who labor en la lucha to protect and save human lives. The visible presence of Latinx in health care professions, like yourself, cannot be underestimated in these efforts to cultivate public trust. No individual or single group of experts working alone will succeed in this struggle to increase vaccinations within nuestras comunidades.

In a recent tweet, Pope Francis urged us to "reflect on our health systems and ensure they are accessible to all of the sick, without disparity." Through conversations like ours, we engage in service en conjunto to combat a pandemic that has challenged human solidarity yet dares us to draw deeply from traditions of healing nourished by both faith and reason.

En solidaridad,

Miguel