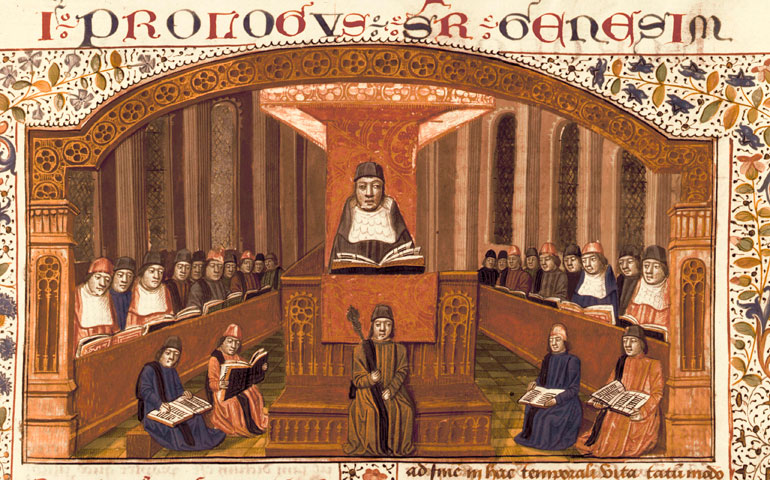

A 15th-century illumination depicts a theological lecture at the Sorbonne in Paris. (Newscom/akg-images)

Editor's note: Following our December editorial on the ordination of women, readers asked us for more background on issues that editorial raised. This is the third article in this series. The first two articles looked at the scriptural and historic evidence of women's leadership in the church.

The proper role and function of the magisterium continue to be a source of controversy in many corners of the Catholic church today. Any fruitful reflection on the magisterium requires that we place the topic in its proper historical context.

Today the term magisterium generally refers to the doctrinal teaching office and authority of the bishops in communion with the bishop of Rome. That more narrow meaning is a fairly recent one. The word magisterium simply means, "the authority of the master or teacher" (magister, magistra) and it was used in a wide range of ecclesial contexts in the early church. Although the term magisterium did not then have the specialized meaning that it carries today, that does not mean that there was no sense of doctrinal authority in the early church.

In the pastoral letters of the New Testament we find officeholders (using the term somewhat loosely) who were recognized for a distinctive teaching responsibility, though the specific character and scope of that authority was not yet established. By the end of the second century, the office of bishop had emerged as an authoritative church office and there was a general conviction that they had in some sense succeeded to the authority of the apostles as guardians of the apostolic faith.

Even as questions of doctrinal authority emerged with considerable vigor in the early church, it would be anachronistic to assume that the church of the first millennium experienced anything like our modern conflicts between the magisterium and theologians. The clear distinction between bishop and theologian that we take for granted today was not nearly as evident in the early church. Most of the church's great theological thinkers were bishops or abbots and there was as yet no separate education for clerics and the relatively few nonclerical theologians that existed.

The distinctive authority of the bishops to make binding doctrinal judgments was fairly well-established by the third century. However, it was most frequently exercised collegially in regional synods and, eventually, in what would be known as ecumenical councils. By the fifth century another decisive factor in the exercise of doctrinal teaching authority had emerged, namely the distinctive prerogative claimed by the bishop of Rome to authoritatively pronounce on doctrinal disputes.

The exercise of doctrinal authority throughout much of the first millennium presupposed several basic convictions. First, the doctrine that the bishops taught pertained to public revelation. There was no sense that bishops received some secret knowledge available only to them. Indeed such a view, known as Gnosticism, had been roundly condemned. Second, what the bishops taught was not foreign to the faith of the whole church. In apostolic service to their communities, the bishops received, verified and proclaimed the apostolic faith that all the baptized in their churches prayed and enacted. The apostolic faith consciousness of the whole people of God would eventually be referred to as the sensus fidelium.

Early in the second millennium, a series of shifts in the understanding and exercise of church teaching authority began to occur. With the birth of the medieval university in the 11th century, a different class of theological teacher would soon emerge, the university professoriate. These theology professors were most often clerics but their education, office and responsibility differed significantly from those of the bishop. Thus in the 13th century we can find St. Thomas Aquinas writing of both the "magisterium of the pastoral chair" (magisterium cathedrae pastoralis), by which he meant the teaching authority of the bishop, and the "magisterium of the teaching chair" (magisterium cathedrae magistralis), by which he meant the teaching authority of the "doctor" or theologian. Of course, Thomas insisted that these magisteria functioned in different ways; only the bishops could normatively assert Catholic doctrine. As Jesuit Fr. John O'Malley has noted, theologians began to be educated in ways that differed from the formation of bishops, who often were more preoccupied with matters of canon law. The conditions were set for a new bishop-theologian relationship. This relationship would flourish when bishops and theologians acknowledged the interdependence of their respective spheres of expertise and authority; it degenerated when cooperation gave way to competition and struggle.

By the late Middle Ages, many doctrinal questions were being handled not primarily by the pope and bishops but by competent theological faculties, like those at the great universities in Paris and Bologna. The active role of theologians working both independently and in partnership with popes and bishops would continue for centuries. For example, theologians played a constructive role at every stage of the Council of Trent (1545-63). And in the decades after Trent it was they, far more than the bishops, who led the theological defense of the faith against the attacks of reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin. The recognition of complementary spheres of authority would soon be challenged, however, by the threatening winds of modernity.

In the 18th century, Pope Benedict XIV created a new teaching instrument, the "encyclical" and in the 19th century these official papal letters, generally addressed to all the church's bishops, would become favored instruments in the expansion of papal teaching authority. Theologians continued to play an important role as consultors in the exercise of doctrinal teaching authority, but the circle of trusted theologians was for the most part now reduced to the theological faculties at the various Roman colleges. As the pope's temporal authority came under attack in the mid-19th century (the Italian nationalist movement demanded that the pope relinquish the Papal States), many compensated by emphasizing the pope's doctrinal authority. This trend culminated in the formal definition of papal infallibility at Vatican I (1869-70).

In the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, popes would begin to offer, as part of their teaching ministry, extended theological treatments issued in formal magisterial documents on important topics. Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) would publish numerous encyclicals on a wide range of theological topics. Pope Pius X (1903-14) would follow Leo's precedent with his 1907 encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis, condemning the evils of modernism. This sweeping condemnation encouraged a veritable witch-hunt for theologians tainted by the scent of "modernism." Indeed the first half of the 20th century saw the hierarchy treat a number of influential theologians harshly because of their views (Marie-Joseph Lagrange, Henri de Lubac, Yves Congar, Karl Rahner, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin).

Both Pius XI (1922-39) and Pius XII (1939-1958) would issue lengthy encyclicals during their successive pontificates, with the latter sharply circum- scribing the legitimate autonomy of theologians. In his 1950 encyclical Humani Generis, Pius XII limited the task of the theologian to that of faithfully explicating that which was proclaimed by the pope and bishops. Theologians were teachers of the faith only by virtue of a delegation of authority from the bishops. They were expected to submit their work to the authoritative scrutiny and potential censorship by the magisterium. "Dissent," understood as the rejection or even questioning of any authoritative teaching of the magisterium, was viewed with suspicion. The dogmatic manuals acknowledged limited speculative discussion that was critical of certain doctrinal formulations but the assumption was that if theologians discovered a difficulty, they were to bring it to the attention of the hierarchy privately and were to refrain from any public speech or writing that was contrary to received church teaching.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-65) did not reflect on the role of theologians in any depth but at numerous points the council affirmed the role they played in the church (Dei Verbum 23; Lumen Gentium 54; Gaudium et Spes 44, 62). Much as at the Council of Trent, theologians and bishops collaborated at numerous points in the process of moving from preliminary drafts to final promulgation of the council's 16 documents.

The council did offer a promising new framework for understanding questions of teaching authority. According to Dei Verbum, the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, the word of God was given to the whole church and not just the bishops. The magisterium was not superior to the word of God but was rather its servant (Dei Verbum 10). Although the bishops would remain the authoritative guardians of that revelation by virtue of their apostolic office, the word of God resided in the whole church as the baptized were given a supernatural instinct for the faith (sensus fidei) that allowed them to recognize God's word, penetrate its meaning more deeply and apply it more profoundly in their lives (Lumen Gentium 12; Dei Verbum 8).

The first decades immediately after the council held promise for this new framework. Pope Paul VI created the International Theological Commission as a way of formalizing a more constructive relationship between the magisterium and theologians. Unfortunately, the commission came under increasing curial control. Hopes for preserving a more positive relationship between bishops and theologians were dashed by Pope Paul VI's final encyclical, Humanae Vitae, which elicited widespread criticism by many theologians (and a number of bishops).

The ambitious pontificate of John Paul II stands as an extended ecclesiastical "reception" of the teaching of Vatican II, particularly regarding its ad extra teaching. Yet in matters concerned with the exercise of doctrinal authority, that long pontificate more closely reflected Pius XII's than the vision of the council. In spite of his moving rhetoric regarding the church as communion, John Paul's policies recalled Pius XII's suspicion of the autonomy of the theologian. The early years of the current pontificate have given no sign of a departure from these policies.

All of this brings us to the present moment. There is no real historical precedent for the plethora of ecclesiastical pronouncements emanating from the papacy (papal encyclicals, apostolic exhortations, apostolic letters, papal addresses), the Curia (curial instructions and notifications of various kinds), and episcopal conference doctrinal committees (notifications and disciplinary actions regarding doctrinal irregularities of one kind or another in the work of various theologians).

Some see this magisterial activism as a necessary ecclesial response to our postmodern information age. In this view, the instantaneous dissemination of information across the globe and the spontaneous eruptions of unregulated theological conversation on countless Internet blogs and Listservs demand a rapid-response system from the magisterium if the integrity of the Catholic faith is to be preserved. Others see such a pastoral response as well-meaning but futile. In our contemporary context, they insist, it is simply impossible to "police" theological conversation in the ways in which it was done in the past. Better for the magisterium to adopt a more modest, humbler mien, one focused on preserving the essentials of the faith. Such an approach would require a more carefully modulated claim to authority, a realistic acknowledgement of the contingent dimensions of many of today's most vexing moral questions (e.g., the changing nature of modern warfare or our evolving understanding of human sexuality), and a greater display of patience in the face of controversial issues that need to be submitted to honest, open debate. The arguments of both sides need to be respectfully considered. We must, however, be clear about one thing: The magisterial activism that we are witnessing today is not traditional; it is quite novel and its merits will need to be assessed in that light.

Next: What is sensus fidelium and how do you know when you have it?

[Richard Gaillardetz is the Joseph Professor of Catholic Systematic Theology at Boston College. He is the co-author with Catherine E. Clifford of Keys to the Council: Unlocking the Teaching of Vatican II (Liturgical Press, 2012).]

Recommended reading

Magisterium: Teacher and Guardian of the Faith by Avery Cardinal Dulles, SJ (Sapientia Press, 2007)

By What Authority?: A Primer on Scripture, the Magisterium, and the Sense of the Faithful by Richard R. Gaillardetz (Liturgical Press, 2003)

When the Magisterium Intervenes: The Magisterium and Theologians in Today's Church, edited by Richard R. Gaillardetz (Liturgical Press, 2012)

The Eyes of Faith: The Sense of the Faithful and the Church's Reception of Revelation by Ormond Rush (The Catholic University of America Press, 2009)

Creative Fidelity: Weighing and Interpreting Documents of the Magisterium by Francis A. Sullivan, SJ (Wipf & Stock, 2003)