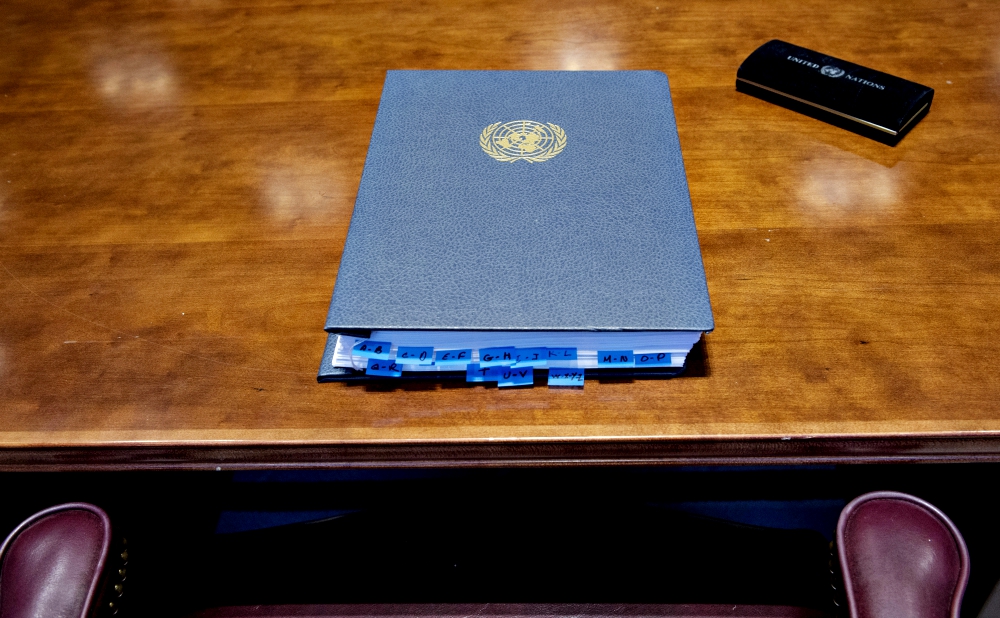

The book of signatures at the signing ceremony for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is seen at the United Nations in New York City Sept. 20. (U.N. photo/Kim Haughton)

A new treaty that opened for signature Sept. 20 at the United Nations and that could be the first step toward worldwide nuclear disarmament has been signed by the Vatican and endorsed by leading Catholic ethicists.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons would stop countries from "undertaking to develop, test, produce, manufacture, acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, as well as the use or threat of use of these weapons," according to a U.N. press release. If it gains the signature and ratification of 50 states, it would become the first legally binding treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons.

"Just as bans have been ratified on other weapons of mass destruction, including cluster munitions, land mines, and chemical/biological weapons, so too it is hoped that a ban on nuclear weapons would reduce the likelihood of their use," Tobias Winright, associate professor of theology at the Albert Gnaegi Center for Health Care Ethics at St. Louis University, told NCR.

Archbishop Paul Gallagher (CNS/Robert Duncan)

Archbishop Paul Gallagher, Vatican foreign minister, signed the treaty at the United Nations Sept. 20. The treaty would enter into force 90 days after at least 50 countries both sign and ratify it. As of Sept. 25, 53 countries have signed and three have ratified it, including the Holy See.

In July, after four months of negotiations, the final draft of the treaty was approved, with 122 countries voting in favor, one against and one abstention.

None of the world's nine nuclear powers — China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States — participated in the negotiations. Only one NATO state, the Netherlands, participated, and provided the sole vote against the final draft.

The treaty opens for signature at a time when conflict between the United States and North Korea has raised the fears of nuclear war to heights not seen since the Cold War, and the U.S. Senate is debating a Pentagon funding bill that would allocate money for a new nuclear weapons program.

When the final draft was announced, France, the United Kingdom and the United States said in a press release that they "do not intend to sign, ratify or ever become party to [the treaty]. Therefore, there will be no change in the legal obligations on our countries with respect to nuclear weapons. ... This initiative clearly disregards the realities of the international security environment. Accession to the ban treaty is incompatible with the policy of nuclear deterrence, which has been essential to keeping the peace in Europe and North Asia for over 70 years."

Some analysts have expressed agreement with that joint statement. Physicist Peter Zimmerman, former chief scientist of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and science adviser for arms control in the State Department, wrote in The Washington Post that "there is a risk in aiming for total nuclear disarmament, because deterring nuclear war isn't their only legitimate use. Nuclear weapons also deter conventional war. ... It's good thing, then, that the Treaty is probably going nowhere."

Advertisement

The Vatican has expressed skepticism of deterrence policies as far back as 1965. The Second Vatican Council's Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudium et Spes, said that while stockpiling weapons of mass destruction could serve as a "deterrent to possible enemy attack," people "should be convinced that the arms race in which an already considerable number of countries are engaged is not a safe way to preserve a steady peace, nor is the so-called balance resulting from this race a sure and authentic peace."

Sept. 26 is the International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons.

"I doubt we can totally put the nuclear genie back in the bottle and be absolutely certain that the cap on that bottle is 'child-proofed' and locked," Winright said. "But the same can be said about other weapons of mass destruction. Even if we cannot achieve absolute zero nuclear weapons, we should approximate it as much as possible."

Winright questioned the value of nuclear deterrence, comparing it to the supposed deterrent effects of the death penalty. "How can it be proven that nuclear weapons or the death penalty actually deter?" he said.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, center, speaks at the signing ceremony for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Sept. 20. (U.N. photo/Kim Haughton)

Even if the world's nuclear powers are not on board with the deal, Winright says, "the ban will cast a shadow upon them, making them pariahs in the global community of nations that we need to be building up."

The U.S. bishops have also consistently promoted nuclear deterrence only as a step toward disarmament. "Deterrence is not an adequate strategy as a long-term basis for peace; it is a transitional strategy justifiable only in conjunction with resolute determination to pursue arms control and disarmament," the U.S. bishops wrote in their 1983 pastoral letter, "The Challenge of Peace."

The difficulty with nuclear deterrence, said Jana Bennett, professor of theological ethics at the University of Dayton, "is that there is nothing specific and achievable — only a vague sense that we've got to be bigger than the other guy so that nothing bad happens."

"For Christians, being bigger than the other guy is not the point. In fact, Jesus constantly asks us to seek solidarity with the small and the oppressed," she told NCR.

A joint declaration from U.S. and European Catholic bishops acknowledged the treaty when the final draft was released in July. "The indiscriminate and disproportionate nature of nuclear weapons, compel the world to move beyond nuclear deterrence," the bishops said. "We call upon the United States and European nations to work with other nations to map out a credible, verifiable and enforceable strategy for the total elimination of nuclear weapons. This goal is achievable if all nations, nuclear and non-nuclear alike, work together."

Catholic organizations in the U.S. have joined in the effort to promote the treaty.

Pax Christi USA and Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns both signed a statement in favor of it, and Pax Christi USA has been urging Americans to contact the United States' ambassador to the U.N., Nikki Haley, in support of the treaty.

Sr. Stacy Hanrahan, who represents the Congregation of Notre Dame at the United Nations, urges Catholics to raise awareness at the parish level and to learn about the issue from reputable sources, like the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

[James Dearie is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Contact him at jdearie@ncronline.org. Material from Catholic News Service was used in this report.]