Voters wait outside a polling location for the presidential election Nov. 8, 2016, shortly after polls opened at Annunciation Church in Philadelphia. (CNS/Tracie Van Auken, EPA)

This, our sixth survey of American Catholics, took place in a time of tension, change and uncertainty in the Catholic Church in the United States. Pope Francis, who had begun his fourth year as Bishop of Rome and Vicar of Jesus Christ, was speaking truth to power as he challenged the president of the United States for his statements about climate change and immigration. Meanwhile, the U.S. Catholic bishops were facing challenges of their own in their efforts to support immigration reform, influence health care legislation, and promote religious liberty. And as public opinion polling centers were proclaiming "the end of white Christian America," many white Catholics were having second thoughts about the president they had voted into office.

The survey, which took place in May 2017, focused on the attitudes and behaviors of a rapidly changing Catholic population in the United States, but also included questions about the 2016 national presidential election, in which religion was more openly involved than it had been since the 1960 presidential campaign of the first ever Catholic candidate, John F. Kennedy. The focus of this article is the 2016 election with an emphasis on a comparison of the beliefs, values and behaviors of Catholics who supported Trump with those who supported Clinton.

Both candidates — and their running mates — were covered regularly in the press for their religious behavior (or lack thereof) and for invoking religion in their campaigns. The Democratic candidate in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton, is a church-going Methodist who is knowledgeable about the Sunday readings. An interesting example of her knowledge was her reference to the story of the prodigal son while speaking to a congregation in Detroit. Clinton said the passage helped her in "those difficult times in my life."

The Republican candidate, now President Donald Trump, was baptized a Presbyterian but was not known to be a church-goer. During the campaign of 2016, candidate Trump was exposed in the media, bragging about a variety of sexual acts that were seen as hampering his chances of being elected. He selected as his vice-presidential running mate the governor of Indiana — Mike Pence, a former Catholic who became an active evangelical during his college years and promoted their beliefs, especially regarding his opposition to abortion, as a governor of Indiana and then as a vice-presidential candidate.

Clinton chose as her vice-presidential running mate Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia, an active Catholic who had taken a year off from law school to volunteer with Jesuit missionaries in Honduras. His background and campaigning in many ways reflected the social justice values espoused so strongly by Pope Francis. Clinton and Kaine supported the Democratic Party's family planning and abortion rights plank, but tried to focus more attention on social justice issues.

Trump and Pence won the election in the Electoral College, but Clinton and Kaine prevailed in the popular vote, with nearly 3 million more votes. Nevertheless, Trump moved into the White House, while the Republicans maintained control of the House and more narrowly of the Senate. It is in this context that we turn now to our survey of American Catholics as they looked back on the election that had taken place some six months earlier.

According to our May 2017 survey, just over three-quarters of American Catholics said that they voted in the November 2016 presidential election. Of those who voted, 43 percent said they voted for Trump while 48 percent said they voted for Clinton. The other nine percent voted for minority candidates. This is fewer Trump voters and more Clinton voters than the percentages among self-identified Catholics as reported in the exit polls, which reported 52 percent voting for Trump, 45 percent voting for Clinton, and 3 percent going to other candidates. But this survey took place six months after the election and some may have been recalling the candidate they wish they had voted for rather than their actual vote.

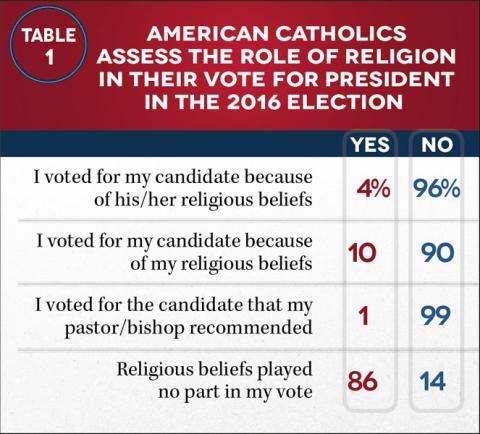

We began our 2017 survey with a series of questions about the possible role religious beliefs might have played among American Catholics In the 2016 election.

The responses of American Catholics to the questions cited in Table 1 make clear their assertion that their religious beliefs were not relevant to their vote for president in the 2016 election. The great majority (86 percent) said that religious beliefs (their own or that of the candidates) played no role in their vote. Just one in ten said that they voted for their candidate because of their own personal religious beliefs and even fewer — just 4 percent — said that they voted for their candidate because of the candidate's religious beliefs.

Beliefs and values that are essential

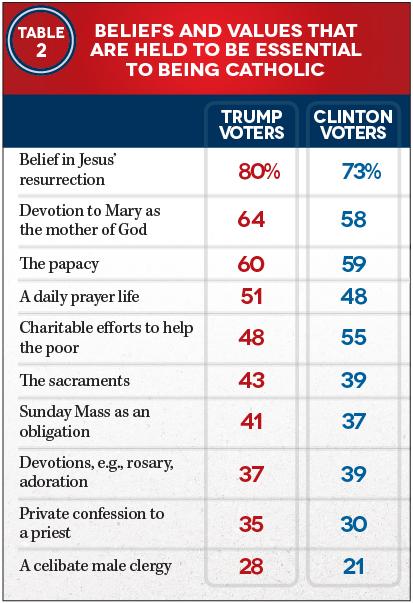

That raised the question whether and to what extent did Catholics who voted for Trump differ in their religious beliefs and practices from Catholics who voted for Clinton. We have a standard block of questions about the beliefs and values that many consider essential to being a "good Catholic" that we have asked, in some form, on every survey since 1987. Table 2 compares the proportion of Trump and Clinton voters who say that each item is "essential to your vision of what it means to be Catholic."

Catholics who supported Trump and Catholics who supported Clinton generally share very similar beliefs about how essential each of these items is to their vision of what it means to be Catholic. Differences of less than 10 percentage points between the two are not statistically significant. Both types of Catholic voters rank all ten items in virtually the same order.

Belief in the resurrection of Jesus, devotion to Mary as the Mother of God, and the papacy are essential to more than half of Trump voters and Clinton voters. Only about half saw charitable efforts to help the poor as essential and the percentage who saw the celibate male clergy as essential continues to have only a small percentage of support among either Trump or Clinton voters.

Loyalty to the church and its leaders

About half of adult Catholics (50 percent among Trump supporters and 54 percent among Clinton supporters) said that Catholics can disagree with church teachings and still be loyal to the church. At the same time only about a third of Catholics (37 percent among Trump supporters and 33 percent among Clinton supporters) said it was important to them to have younger members of the family grow up as Catholics. The implications of this finding should be of concern especially to church leaders and Catholics who believe that the Catholic Church is a positive force in American society.

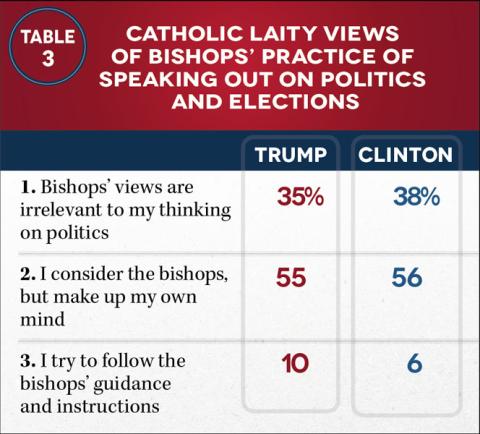

We asked a series of questions about Catholic laity’s responses to Catholic bishops speaking out on politics and elections.

More than half of the Catholics who voted for Trump or Clinton asserted that they make up their own minds on matters of politics and elections, while a third or more said the bishops’ views were irrelevant to them. One in ten Trump supporters and 6 percent of Clinton supporters said they “try to follow the bishops’ guidance and instructions on political and public policy matters.”

However, when we asked about the bishops’ support for expanding government-funded health insurance, only 14 percent of Catholics who voted for Trump “strongly agreed” with the bishops, while 59 percent of Catholics supporting Clinton agreed strongly with the bishops. Only 7 percent of Clinton Catholics disagreed with the bishops’ support, while 56 percent of Trump Catholics disagreed with the bishops on this issue.

On the bishops' stance in opposition to the death penalty, 63 percent of Trump Catholics disagreed with the bishops’ opposition to it. In contrast, 65 percent of Clinton Catholics supported the bishops in their opposition to the death penalty.

Finally, with regard to the bishops' support for making the government immigration process easier for families, 45 percent of Catholics supporting Trump agreed with the bishops, while twice as many Catholics (92 percent) who supported Clinton agreed with the bishops on this issue.

These three political issues have been promoted much more by the Democratic Party than by the Republican Party, as the voting patterns make clear.

The impact of religion on American life

We found mixed responses when we asked respondents whether they thought that religion as a whole was increasing or losing its influence on American life.

| Trump | Clinton | |

| Increasing its influence | 11% | 13% |

| About the same | 25 | 39 |

| Losing its influence | 64 | 48 |

In general, Clinton voters were more likely than Trump voters to say that the influence of religion on American life was "about the same." Trump voters, in contrast, were more likely than Clinton voters to say that religion was "losing its influence."

We followed that question with another: "All in all, do you think this is this a good thing or a bad thing?"

| Trump | Clinton | |

| A good thing | 30% | 46% |

| A bad thing | 70 | 54 |

We found that Clinton voters are more likely than Trump voters to say that their evaluation of the influence of religion on American life was "a good thing." In other words, Clinton voters, a majority of whom see religion as having about the same influence or an increasing influence on American life, also see that as a good thing. Trump voters, on the other hand, the majority — nearly two in three — of whom say that religion is "losing its influence" on American life also judge that as "a bad thing."

We asked "How important is the Catholic Church to you personally?" We found that Trump voters and Clinton voters were virtually identical in the importance they place on the Catholic Church in their lives. More than a third (38 percent of Trump supporters and 36 percent of Clinton supporters) said that the Catholic Church is the most important, or among the most important parts of their life. About a quarter of Trump voters and a similar proportion of Clinton voters said that the Catholic Church is not very or not at all important to them.

Advertisement

| Trump | Clinton | |

| It is the most important part of my life | 10% | 9% |

| Among the most important parts of my life | 28 | 27 |

| Quite important, as are other things | 35 | 37 |

| Not terribly important to me | 22 | 22 |

| Not very important to me at all | 5 | 6 |

When we asked these Catholics whether they think that Catholicism is increasing or losing its influence on American life, Clinton voters were a little more likely than Trump voters to say that the influence of Catholicism was "about the same."

| Trump | Clinton | |

| Increasing its influence | 9% | 10% |

| About the same | 30 | 43 |

| Losing its influence | 61 | 47 |

Trump voters were more likely than Clinton voters to say that Catholicism is "losing its influence" on American life. When we then asked them whether this is "a good thing" or "a bad thing" 69 percent of Trump voters and just over half of Clinton voters (53 percent) see this as "a bad thing."

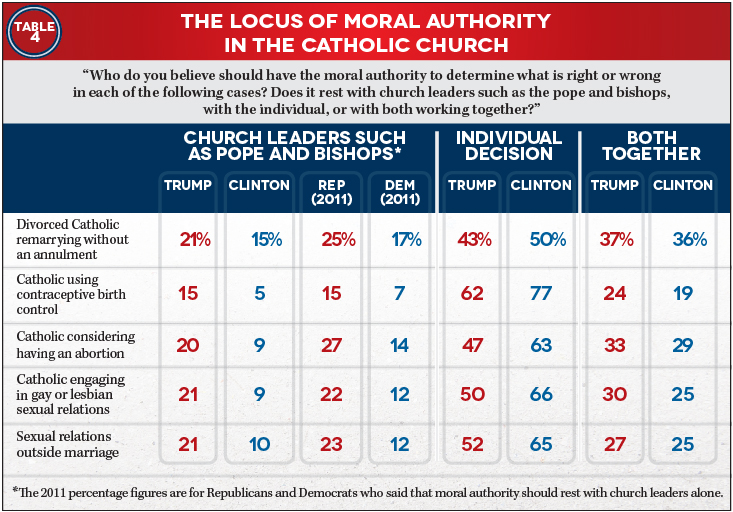

Perhaps no set of questions has revealed the challenge facing church leaders in their efforts to maintain their moral authority than the questions we have asked in the recent surveys regarding the locus of moral authority in several situations.

(NCR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Only about one in five or fewer Trump voters or Clinton voters think that the locus of moral authority for these decisions rests with church leaders. Compared with the same questions in our 2011 survey, we see that even fewer Catholics feel this way than they did in 2011. The plurality of Trump voters — and a majority of Clinton voters — feel that the individual has the moral authority to determine what is right or wrong in each case.

It's hard to say just what all this means. In many ways, except for their voting behavior, Trump Catholics and Clinton Catholics look very similar. They hold very similar core beliefs about the essential aspects of their Catholic faith. They share similar values; they are equally strong in their attachment to the church; they similarly agree that one can disagree with church teachings and still remain loyal to the church.

A majority in both camps say that they consider what the bishops have to say about politics and policy but then make up their own mind. When the bishops' stance on political issues aligns with their party's position, they agree with the bishops. But they have no problem disagreeing with the bishops when their political party is in opposition. Finally, the data suggest that Trump Catholics are slightly more pessimistic than Clinton Catholics in their evaluation of the influence of religion in general, and Catholicism in particular, on American life.

D'Antonio has taught at Michigan State University and the University of Notre Dame, where he served as chair of the sociology department from 1966-71. He moved to the University of Connecticut in 1971 as professor and chair of the sociology department, and later served as executive officer of the American Sociological Association from 1982-91.]