Holocaust survivor Max Glauben films a segment in an interactive green-screen room for the Dallas Holocaust Museum. (Courtesy McGuire Boles/Dallas Holocaust Museum)

At 91, Max Glauben is still telling his story to anyone who will listen.

Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1928, Glauben helped found the Dallas Holocaust Museum Center for Education and Tolerance in 1984, and ever since he's been talking to school groups and museum patrons, as well as to the teens who accompany him on his frequent trips to Israel and the concentration camps of Eastern Europe.

"Max Glauben is a source of inspiration for anyone who has met him," said Mary Pat Higgins, president and CEO of the Dallas museum. "He inspires me daily. His resilience and forgiveness and what he's made of his life gives me hope in humanity."

And now, thanks to technology that is transforming the world of Holocaust remembrance, Max Glauben will be speaking and answering students' questions in perpetuity.

Time has long posed a problem for Holocaust museums. Since the first Holocaust remembrance centers were established after World War II — Los Angeles' museum, which opened in 1961, was the first in the United States — Holocaust survivors themselves have been the most effective way to bring the Holocaust's horrors home.

But with this September marking 74 years since the war ended, museum officials are concerned with how to extend this precious resource for remembering the catastrophe. Most of the Holocaust survivors are in their last decade of being able to give their first-person testimony.

Now the Dallas museum and others across the country are benefiting from hologrammic technology, created by the USC Shoah Foundation at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, which allows them to preserve the images and voices of survivors in a way that brings them alive for museum visitors.

A hologram is a 3D photograph of a person that, when lit properly, captures the person's physical presence. Hologrammic films assembled from thousands of these 3D images can bring to a darkened theater the person seemingly in full: "the way he taps his foot and moves his hand," said Kia Hays, program manager of USC's Dimensions in Testimony Interactive Experience, of the hologram of Glauben, which will be unveiled in a purpose-built theater this September.

Combined with a cutting-edge artificial intelligence program that can retrieve pre-recorded responses on a range of frequently asked-about topics, the hologram can make it seem as if the person is there.

The magic of saving Max Glauben for future generations is as difficult as it sounds.

For one, the technology is expensive, costing $2.5 million to record a single person.

Advertisement

The Dallas museum commissioned its hologram of Glauben to help debut a new, elaborately designed 55,000 square-foot home on nearby Houston Street, set to open Sept. 17 as the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum. In May of last year, Higgins was enmeshed in a six-year campaign to raise $71 million dollars for the new building, but fundraising was going well enough that she and her board of directors decided to add the cost of the hologram, if the USC Shoah Foundation approved their candidate.

Not every survivor is equal to the challenging process of making a hologram. Even those who are practiced storytellers (many survivors find it too painful to stir up memories) must go through a careful selection process by the Shoah Foundation to see if they are up to the rigors of spending a week being filmed from nine angles by 18 cameras, answering about 1,000 questions that the filmmakers anticipate visitors might ask during a 45-minute experience.

About 350 of the questions have been the same for all the survivors. The rest are personalized to each one's experience. None of the responses are edited, manipulated or changed.

It helps that the technology has evolved enough to allow the USC team to bring its production to the survivors. When the program started, survivors had to go to the USC Shoah studio in Los Angeles.

The foundation accepted Glauben last summer, and in August he became their 18th 3D holographic image. Hays said she was struck by Glauben's "incredible memory" and "incredible personality."

Steven Spielberg founded the Shoah Foundation in 1994, the year he won the Academy Award for directing the Holocaust film "Schindler's List," to preserve interviews with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust.

The foundation houses nearly 55,000 audio-visual testimonies conducted in 65 countries and in 43 languages. But this new technology addresses a unique need — a way of giving the feeling that the survivors are still with us, Hays said.

Survivors, Hays said, "are our best teachers. I think we're seeing how important it is in this day and age to understand what has happened in the past, to make connections between the past and present and to remind students that they can make change for the good."

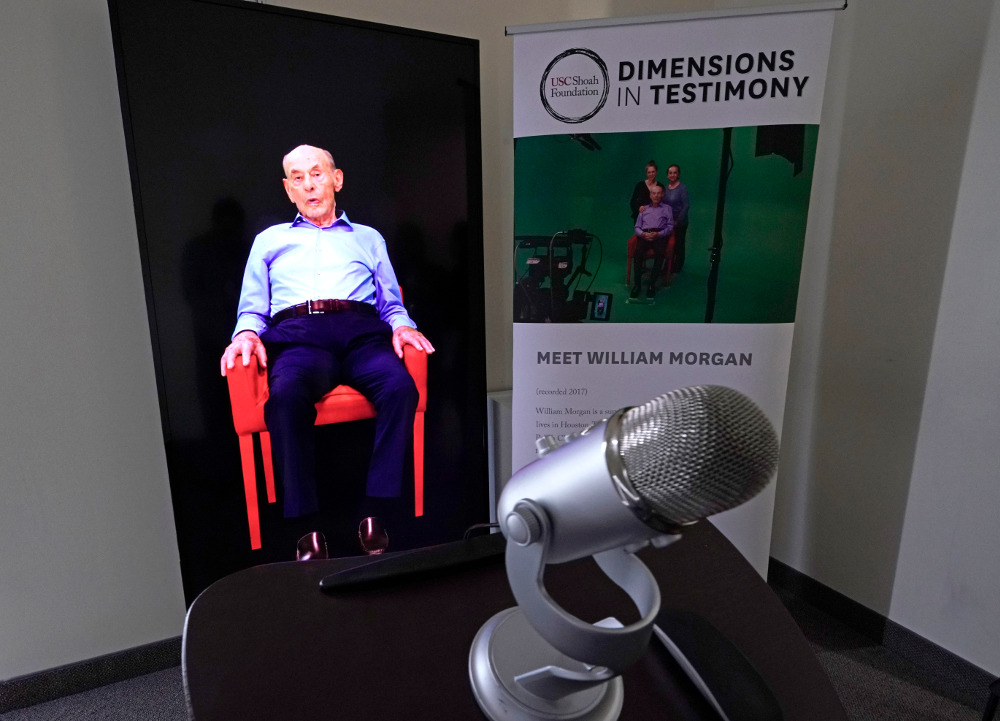

A Dimensions in Testimony exhibit featuring Holocaust survivor William Morgan using an interactive virtual conversation is shown at the Holocaust Museum Friday, Jan. 11 in Houston. The University of Southern California Shoah Foundation has recorded 18 interactive testimonies with Holocaust survivors over the last several years. (AP/David J. Phillip)

Meanwhile, Glauben continues to share his in-person testimony with visitors to the Dallas Holocaust Museum Center. On Feb. 27, he addressed a packed room of teens.

He spoke softly of growing up during the Holocaust, and their attention was pulled as if by invisible threads. They listened, riveted, as he described the fear, the hunger and desperation in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The stillness intensified as Glauben talked about the suffocating cattle car ride to the concentration camps, how he struggled to catch up to his little brother and mother on disembarking, only to be restrained by his father who knew that his mother and brother were going to their deaths.

Glauben described going with his father to the Budzyn labor camp in Poland and the day he woke and walked out to the courtyard to find his father's boots in the courtyard. Just boots. No body. That was the day he knew he was an orphan. He was 13.

"The loneliness," he said softly in a private interview. "It's an indescribable feeling."

He talked to them about the terrible things that can happen when people give in to prejudice. He told them to persevere even when things seem unbearable, to know that they, like him, can survive and find happiness.

After coming to the U.S. as a teenager, he served in the U.S. military, married, worked and had children and grandchildren. He smiled, his face softening when he talked about his family.

His name, Glauben, he told the students, is German for believe.

After the presentation, teens clustered around him, asking him questions. He stayed to answer every one.

It gives him comfort that one day, after he can't answer those questions in person, his hologram will.