Pope Francis greets people as he leaves an ecumenical prayer with migrants in the Church of the Holy Cross Dec. 3 in Nicosia, Cyprus, Dec. 3. (CNS/Paul Haring)

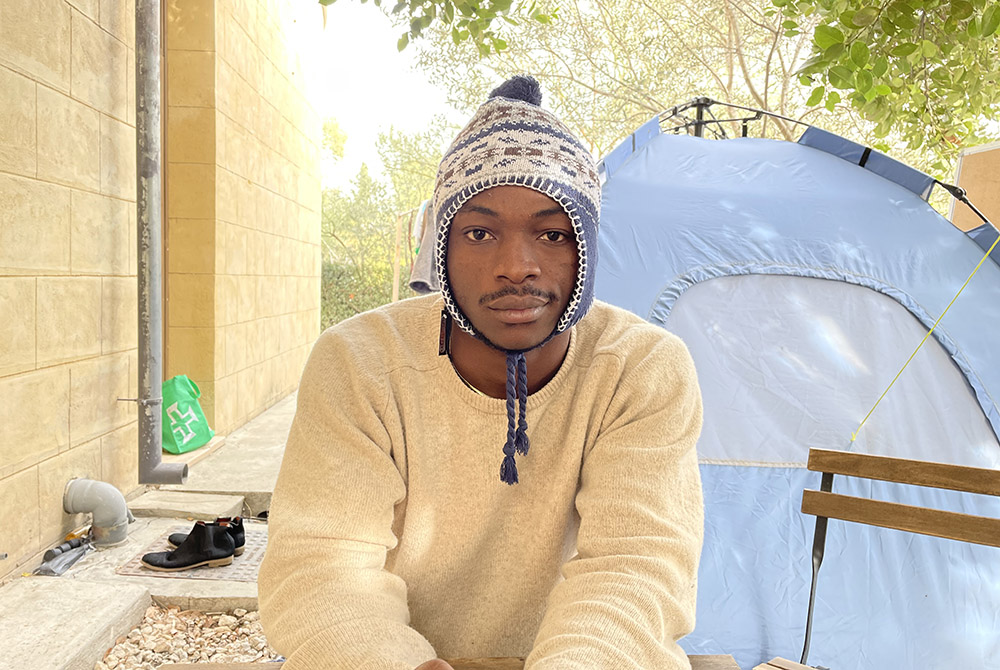

Twenty-year-old Daniel Ejuba, a refugee from Kumba, Cameroon, has spent the last six months living in a tent in the United Nations' controlled buffer zone that separates Cyprus' divided capital of Nicosia, following a failed effort to escape from the north to the south.

Most days are monotonous but today — on Dec. 3 — he has been given some hope: Pope Francis is in town and Ejuba hopes to be one of the estimated 50 refugees the Vatican has arranged to transfer from Cyprus to live in Italy.

Ejuba, however, may be the only person coming from the north of Nicosia who is excited for the pope's visit, as most of its non-practicing Muslim-majority residents are blissfully unaware (or in a few cases, apathetic and amused) that the leader of the world's 1.3 billion Catholics is in town.

For more than 180 days, Ejuba has lived in no man's land, spending his days watching movies on his cellphone and moving between the inflatable mattress inside his tent and a small outdoor table next to his makeshift residence in the middle of Cyprus' dividing line.

With Francis' arrival, however, that might soon change.

Migration has taken center stage during Francis' first 24 hours in Cyprus, which has more refugee arrivals than any other country in the European Union, with the pope telling both church and civic leaders on his first day in the country that welcoming new arrivals is "precious" work.

"Thank God for him," Ejuba told NCR just hours before Francis was set to join migrants in an ecumenical prayer service. "No one is interested in our case except him. I pray God will give him good health, prosperity and many more years."

Ejuba, who is Catholic, first arrived in northern Cyprus in March, fleeing tribal violence in his native Cameroon. Unable to speak Turkish and faced with limited prospects in the north, last June, he and another Cameroon refugee paid someone several hundred euros to guide them to a spot where they could jump across the dividing wall, only to land in the buffer zone where they were detained by United Nations police.

Given the surge of refugees in the south, the Greek Cypriots refused to accept them. They have since been provided a temporary shelter in a tent behind the Home for Cooperation, a bridge-building educational center that was founded in 2011.

Yet despite its efforts to bring together both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, the Home for Cooperation cannot provide a permanent residence for the likes of Ejuba. Instead, its mission is to provide a space for encounters for neighbors on both sides of the "Green Line" that has divided the capital since 1974.

Calls for "One Cyprus" are written in graffiti in the U.N. controlled buffer zone in Nicosia. (NCR/Christopher White)

Yet the "pope of encounter" — who has spent the last eight years of his papacy emphasizing the importance of dialogue and who pleaded for Cyprus' reunification in his first speech on the island on Thursday, Dec 2 — may find it difficult to make any progress in solving the "Cyprus problem," as it is commonly known.

On Nicosia's southern Greek side, which is over 80% Orthodox, storefronts are outfitted with Christmas decorations and the old town is effectively limited to pedestrian movement, with everyone aware that Pope Francis is in town.

In the Turkish-controlled north, street traffic moves along swimmingly. There are, of course, no Christmas wreaths and lights in the Muslim-majority territory, but the cafes are buzzing.

Francis spent his first full day in Cyprus visiting the leadership of the Orthodox church and celebrating a Mass attended by an estimated 10,000 Greek Cypriot Catholics, Maronite Catholics from neighboring Lebanon and other foreigners who live on the island. Less than a few miles away on the Turkish side of Nicosia, the pope's visit barely registered among residents.

"This is like a joke," remarked Umay Yilmaz, a 35-year-old Nicosia native from the north.

As she stood outside of Ovis Coffees, a trendy cafe in Atatürk Square, just a few blocks away from the administrative center of the northern part of Nicosia, she let out an exasperated laugh.

"We have basic problems, like running out of oil, but the pope is coming and I am supposed to care?" she said in an interview with NCR. "I even wrote about this on Facebook! Will he [Francis] need oil to come here?"

Advertisement

It's not that Yilmaz is opposed to reunification efforts. In fact, she recalls when Pope Benedict XVI visited Cyprus in 2010. Benedict, like Francis, only visited the Greek Cypriot side of Nicosia in an effort to not anger leaders from the Orthodox church who have a contentious history with their Turkish neighbors.

"Social media wasn't around as much then, but I remember the photos of that visit," she recalled. "I was more hopeful then, but I guess it was because I was younger."

A "Remember Cyprus" sign above the "Green Line" separating Nicosia, as seen from the Greek-controlled south. (NCR/Christopher White)

During the major reunification referendum in 2004, Greek Cypriots voted overwhelmingly — by 75.8% against a peace plan. Turkish Cypriots, by a solid majority of 64.9% voted in favor of it. Subsequent peace talks have also failed, and while the conflict is not presently violent, activists fear that maintaining the status quo without any movement toward reconciliation is like waiting for a volcano to erupt.

"I want this island to be free," Yilmaz reflected. But she expressed skepticism that a religious or political leader, including the likes of Pope Francis, would be the impetus for that.

"The pope is just another tourist," says a middle-aged woman working in the garden cafe at Rüstem's rare bookshop, who declined to give her name. A group of six high school-aged boys acknowledge that they know who Pope Francis is, but are all unaware that he is currently in town.

The Kıbrıs Gazetesi, the highest circulation daily paper, carries a small article noting that Ersin Tatar, president of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (which is only recognized by Turkey and no other country), is disappointed that Pope Francis has not chosen to visit the north, especially given his past outreach to the Muslim world.

Many more column inches are dedicated to another article with the headline: "Running out of fuel, stations closed."

Hediye Amcaoglu, 25, who was born in Turkey and moved to the north of Nicosia with her family at age 12, says that she would only be interested in a papal visit "if the lira goes up."

"I want to become a banker, but I need to go to university," she says, and then with a bit of resolve, adds: "I will go to university."

Nearby, underneath a tree on a park bench sits 75-year-old Ziyashah Orhan. Despite the warm weather, he is wearing a full navy suit and red tie, matched by a lapel pin of the Turkish flag.

"I watched the pope on television," he says nonchalantly in an interview with NCR, adding that he is opposed to reunification efforts.

"They hate us," he says matter-of-factly of the Greek Cypriots. "But I do not hate anyone."

"Your Wall Cannot Divide Us" reads graffiti outside of the UN buffer zone of Nicosia. (NCR/Christopher White)

"By age 7, my family had moved three times," he said, describing his early nomadic existence due to the conflict between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

"I don't think I have ever lived a good day," he says, reflecting on this past. When asked whether he would like for the pope to visit the north, he says, "Sure."

"He can see how we live," he added. "Come visit us."

As he spoke to Cyprus' president and other civic leaders upon arriving on the island, Francis described the nation as the "pearl" of the Mediterranean and called upon its leaders to reject past divisions and embrace bridge-building.

"Peace is not often achieved by great personalities, but by the daily determination of ordinary men and women," he said Thursday. "For it will not be the walls of fear and the vetoes dictated by nationalist interests that ensure its progress."

Yet on Friday, Dec. 3, the pope's inspiring words were matched with challenging realities on the ground.

"Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus FOREVER," read the banner above one side of the checkpoint that divides Nicosia. On the other side, a sign on the Greek controlled south states that "Nothing is gained without sacrifices and freedom without blood" — with both sides and signage flanked by armed guards.